- The Constitution: Article 30 of the Constitution of India gives minorities the right to set up “educational institutions”

- The 1967 SC Ruling: This ruling had taken away the minority status of AMU, but in 1981, Parliament restored it

- Possible Outcome: If the SC strikes down AMU’s minority status, that would apply to all other minority universities.

***

The controversy over the minority status of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) involves vital questions of the status of the minorities in a democracy. Chief among the issues is the privileges—indeed the constitutional rights—a democracy accords a minority group. What sharpens the antagonism is the fact that the government is led by a party that comes to these issues with a lot of accumulated resentment. And it’s drawing on a much-criticised 1967 judgement of the Supreme Court in an attempt to dilute the right of the minorities to establish institutions of higher learning. The quibble is over the word “establish”—since universities are actually established by acts of Parliament or state legislatures, a community cannot technically be said to have established them. To go by that reasoning would mean that a minority group can henceforth set up only educational ‘institutions’, as Article 30 sets out, but not universities. A matter of letter versus spirit.

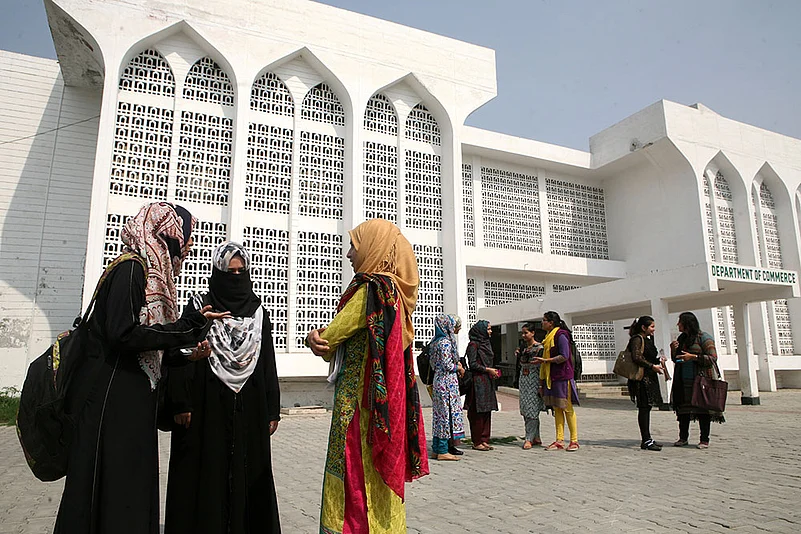

As Brig (retd) Syed Ahmad Ali, pro vice-chancellor of AMU put it, “AMU is a secular university with a Muslim ethos, with representation of all communities. We don’t even have a quota for Muslim students. But it is of sentimental value to have minority status—a university for Muslims to call their own.” The grace of according that, however, was missing in attorney-general Mukul Rohatgi’s statement to the apex court in January, on behalf of the BJP-led NDA government: “It is the stand of the Union of India that AMU is not a minority university. As the executive government at the Centre, we can’t be seen as setting up a minority institution in a secular state.” This about-turn from the previous UPA government’s support to AMU prompted Justice M.Y. Eqbal (now retired) to ask if this was the outcome of a change of government. To which Rohatgi replied evoking the 1967 judgement: “The previous stand was wrong. The law laid down in Azeez Basha case by a five-judge bench of the SC on October 20, 1967, still holds good. It had ruled that AMU was not a minority institution. As per the Centre, this judgement still holds the field. Now, it is for the university, whether it adopts a contrary view.” (In 1981, though, Parliament reaffirmed AMU’s minority status, superceding the judgement by amending the AMU Act of 1920.)

The Opposition seized on the issue, turning up the heat in Parliament in March and leading to an adjournment. Some legal experts too are appalled by the government line. “How on earth can a minority possibly ‘establish’ a university except by asking the government to get enacted a law incorporating the body it had formed thus and conferring on it a legal personality?” asks constitutional expert A.G. Noorani in a recent publication. And Ram Jethmalani, who had introduced a private member Bill for AMU’s minority status as a BJP MP in 1980, says, “I’m for them. AMU is one of the greatest achievements of the Muslim community in India. What is this silly argument that it was set up by Parliament? There is nothing to gain by destroying its minority status. It’s only good for Indian secularism that it remains.”

The government seems to be telling the minorities they can only have minority institutions—not universities. And by extension, that anyone can set up a university except the minorities. Says Romy Chacko, who represented St Stephen’s College in its 1992 minority status case, “I’d advised St Stephen’s not to opt for university status for they could [technically] lose minority status even if they were successful.”

Since minority groups are allowed by Article 30(1) to establish and administer educational institutions, there’s more than the power to just confer degrees: they may impart specific religious or linguistic education. Besides, minority institutions are exempt from reserving up to 50 per cent of seats for SCs, STs and OBCs; they may INStead reserve up to 50 per cent of seats for their own community and leave the rest of the seats open to the general category. This has major implications for a university like AMU. Without minority status, it will no longer be able to reserve seats for Muslim students and will have to reserve seats for SCs, STs and OBCs, resulting in a sea change in the ethos of the university.

An official at the National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions (NCMEI) suspects that the immediate reason for the government targeting AMU might be the Uttar Pradesh elections next year. Says an official in the HRD ministry, “This is a way of consolidating Dalit votes.” Another explains, “This government knows it can’t get the Muslim vote, so it hopes that once more seats in minority universities are opened up for SCs, STs and OBCs, the ruling party can woo these sections.” Surprisingly, a leader of a party the BJP is allied with agrees. He had told Outlook, “This will cause a rift between Dalits and Muslims. At an NDA meeting, I tried to explain to senior BJP leaders that this would have far-reaching effects—it could affect Jain, Buddhist and Christian universities as well. What about DAV College in Punjab, which is a Hindu minority college according to the Supreme Court? This will hit us politically as the minorities will be unhappy. I am confident the A-G will not make any statement on this.” But on April 4, the government did indeed tell the court that its stand on AMU’s minority character remained unchanged and it would file a revised affidavit by June.

Some lawyers, like Vedanta Varma, believe there is no need for the government to have jumped into the fray, for it was a matter between the AMU and the courts. “It was a political move, both by the UPA—to support AMU—and by the NDA—not to support AMU,” he says. History seems to suggest parties in or out of government have flip-flopped on the issue as expediency dictated. During the UPA regime, Kapil Sibal, as HRD minister, reportedly opposed minority status for Jamia Millia Islamia, a central university. In 1977, the BJP’s precursor, the Jana Sangh, supported minority status for AMU. In 1979, the demand for minority status for AMU was part of the Janata Party manifesto, with latter-day BJP stalwarts Advani, Vajpayee and Subramanian Swamy supporting it. And in 1981, these leaders had supported the Indira Gandhi government’s amendment that restored minority status for AMU. Last week, though, Swamy was supporting the A-G’s rationale in Parliament, while Sibal now says, “The character of a university doesn’t depend on the state funding it. This stand creates fissures at a time when the country needs healing.”

Outlook filed an RTI application seeking a list of religious and linguistic minority universities in the country. It came back with the reply that the HRD ministry had no information on it. But, as the NDA leader who wants to remain anonymous put it, there are mischief-makers waiting all over the country. And they could move the courts to seek revocation of minority status of insitutions piecemeal. Worse, if the Supreme Court strikes down AMU’s minority status, that would apply to minority universities across the country. Says Faizan Mustafa (see column), vice-chancellor of NALSAR, “The A-G argues that the government cannot by law establish a minority university via Parliament. But deemed universities are set up under the law by the HRD ministry. What Parliament cannot do, the HRD ministry, being inferior to government, can certainly not do either.”

Dr Jetti A. Oliver, chancellor at Sam Higginbotham Institute of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences, Allahabad, a minority university, says, “Minority universities are established ‘by the community’, the government passes the Act ‘for the community.’ If this changes, it’s is a sign of the times. We expect the court to uphold the spirit of the law—which is that the minority community comes together to set up an institution, which is why it’s a minority institution.”

By Anoo Bhuyan in Aligarh

.jpg?w=200&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)