A son recounts how his father, a self-styled lockmaster, caused a deadly river disaster by wielding control rather than violence.

Set in a fractured, post-collapse Europe, the White River becomes a metaphor for borders, guilt, and irreversible loss.

The narrative probes intention versus consequence, as the father later vanishes into the same waters that killed his victims.

Our Elsewheres: Excerpt From The Lockmaster

"A suspenseful, post-climate-collapse drama in which a son searches for the truth behind a deadly river disaster and confronts his estranged father amid a fractured Europe."

My father killed five people. Like most murderers who need only to press a key or push a lever or a switch to elevate themselves for one unfettered instant to the rank of masters of life and death, he did this without touching a hair on his victims’ heads or even looking them in the eye but by means of a series of chrome winches to flood a navigation channel used by riverboats.

The surge of water released by the open sluice gates transformed this narrow channel lined with larch beams into a raging culvert. Instead of gliding gently through it from the upper to the lower reaches of the White River, a languid narrowboat with 12 people on board suddenly gathered speed and shot downstream between moss-covered cliffs. Then, where the passage rejoined the old river-bed, the longboat flipped over in the torrent, as if struck by a giant fist, and tumbled bottom-up through the seething whirlpools and currents.

The roar of the Great Falls, a cascade over 120 feet high which boats were able to bypass via a system of canals my father had regulated—no, ruled over—for almost 30 years, drowned out the horrified shrieks of those gathered on the craggy banks who witnessed the sinking as well as heard the screams and cries for help of the capsized and drowning passengers. All sound not produced by the eddies or the spray or the echo of the whitewater pounding against the rocks was swallowed up by the White River and its falls, a centuries-old source of dread to rafters and watermen.

It was a warm and slightly cloudy early summer’s day, a Friday in May on which, according to a Calendar of the Martyrs observed both then and now, many villages and towns on the banks of the almost 2,000-mile-long river celebrated the feast of St Nepomuk—the patron saint of rafters, bridge-builders and lockkeepers, but above all the custodian of secrets. According to one legend carved in hand-sized gilded letters into a rock beside the Great Falls, Nepomuk, the bishop and imperial confessor of Prague, had refused to divulge a crime an emperor had avowed to him and had, as a result, been tortured and thrown into the swollen Vltava with a grindstone around his neck.

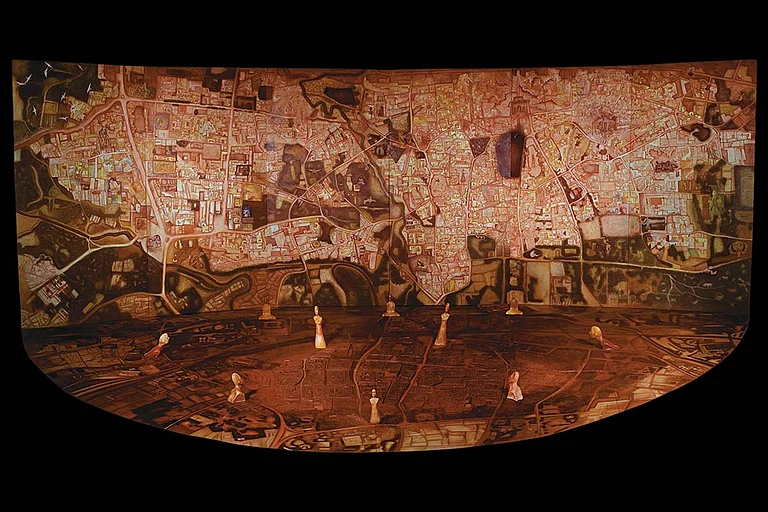

Even though by the time of his feast most ferry connections were already discontinued and many bridges that had once spanned the White River on its way to the Black Sea had been destroyed, the spirit of the bridge protector seemed to hover over dynamited and flooded pillars and shattered steel arches, over remains corroded by rust or crumbling under blankets of moss, smothered by deep-green thickets in the summer months, while in winter they loomed cold and black from the clouds of spray like the ghosts of a world that had sunk into infamy.

Over 40 languages were spoken along the White River, yet the number of bridges that had once stitched its banks together dwindled with every passing year, a clear and dramatic symbol of an age of division and borders. The loss of the bridges had been accompanied by the dissolution of most alliances and ties between states on the European continent, splintering it into a plethora of microstates, tiny principalities, counties and tribal territories, each boasting its own flag and coat of arms. The White River flowed as calmly and inexorably as ever towards a future in which only the occasional rotten barge or cable ferry would ply its way through the gurgling, frothing eddies that licked the rubble jutting from its waters.

Five dead. Whether my father had actually intended to cause so many casualties or a comparably alarming number—or was perhaps even willing to countenance the death of all twelve of the longboat’s passengers—will presumably remain a mystery unless a confession nailed to the sluice gate or some other scrap of evidence turns up among the driftwood and jetsam along the gravel banks to confirm or refute my suspicions. Any question to him is but an echo in the void. On the first anniversary of his deed, as if after precisely one year’s penance he had resolved to atone, he glided along the upper reaches of the White River past a shocked fly-fisherman who shouted a warning as the rock-salt-laden lighter, similar to the narrowboat in which my father’s victims had capsized, headed for the veils of spray of the Great Falls.

He didn’t even glance at the frantically gesticulating angler nor, according to the man’s statement, take a single stroke with his oars to avert the inevitable. And with his cargo, he plunged into the thundering depths.

Smashed planks from his lighter were found on three different sandbanks and gravel shoals; his corpse—despite the deployment of rescue divers, who had never retrieved anything but dead bodies along this stretch of river—never was. And too much time has now passed to find in the deep, or hidden under an overgrown patch of riverbank, even one shard of bone that might be traced back to the missing man.

The rock salt he was transporting must also, I imagine, have wiped out schools of freshwater fish—rainbow trout, pike and char, which beat their fins so frenetically in their panicked escape from the gill-corroding salt dissolved in the swirling currents that they squandered what strength they had left and re-enacted how my father’s victims met their watery deaths.

Shaped like a Venetian gondola, the nearly 30-foot larchwood punt in which my father vanished silently into the Great Falls, like a boatman petrified by guilt, was drawn from the stocks of the open-air museum of river navigation that he had run for decades with an unquenchable hatred for all things modern. After all, if one thing could be said with any certainty about my father—an enthusiastic and sometimes kindly man whose silences could last for days and who had frequent outbursts of rage—it was that he was a man of the past, not only as the administrator of an extensive museum complex but also to the very core of his being.

By the time he was appointed lockmaster and thus curator of the Great Falls Museum in our home county of Bandon, the course of his life seemed to have changed direction, and rather than flowing into a forbidding future, ran backwards out of the fog of this future into a yesteryear that appeared familiar, predictable and amenable.

Centuries earlier, in times that lived on only in my father’s mind, lockmaster had been an honorific title granted to the lockkeepers who diverted the White River around the Great Falls into boat channels built like watery terraces along the cliffs. These had allowed the salt skippers to skirt the Great Falls in their lighters via a series of stepped canals.

His job was to let just the right amount of water into these passages by opening and closing a series of sluice gates, so that even heavily laden salt punts could be carried past the roaring falls and into the lower reaches of the White River on a gentle wave whose force decreased with every yard. Thus, by the end of the deviation, the surge of water would have been sapped by the staggered opening of drain valves and, slowed only by wet larchwood boards, a lighter would slide gently back out onto the river.

A lockmaster exerted such masterly control of the sequential opening and closing of the sluice gates, the valves, the flooding and the discharge, that the boatmen in their descending lighters floated around the Great Falls as if in a cradle or the basket of a hot-air balloon. But woe betide him if he made even one mistake during this descent! A longboat could shoot downstream like a harpoon tip before capsizing and sinking into the whitewater at the end of its passage. The dozens of sailors who had drowned over the centuries of this salt trade were commemorated on plaques screwed into a bare rockface beside the Great Falls or carved, like the legend of St Nepomuk’s drowning, into the stone as intricate ornaments, now coated with moss.

Although the age of the lockmasters was long gone, although the mouths of the salt mines in the Totengebirge mountains, whose towering, cloud-scraping walls bounded the county’s southern horizon, were now scrub-choked or blocked-up portals, and the boat passages overhanging the river mere artefacts to be admired for a modest entry fee, although he was the curator, my father stubbornly insisted on being addressed as lockmaster.

Shortly before the latest ethnic laws forced my mother Jana to leave him and return to her native Adriatic shores, she embroidered the chest pocket of one of his shirts, where he always kept the river-flow chart handy, with his title in silver thread: Lockmaster. I now know that even without this ethnic cleansing, Jana would probably have left my father because she could no longer stand Bandon’s universal hatred of all things foreign nor my father’s hatred for every aspect of contemporary life.

Lockmaster! To me and my sister Mira, who had overheard local people make sarcastic jibes and giggle about the curator’s self-appointed title, it seemed at the time as if, before her departing, our mother had embroidered a mocking nickname on his chest, and he took it with him to his doom.

A suspenseful, post-climate-collapse drama in which a son searches for the truth behind a deadly river disaster and confronts his estranged father amid a fractured Europe, exploring guilt, legacy, and forgiveness.

CHRISTOPH RANSMAYR, the Austrian novelist, blends myth, history and speculative reframing in acclaimed books such as The Dog King and The Terrors of Ice and Darkness. His work probes postwar memory and alternative histories.

(Excerpted with permission from Seagull Books)