For Adivasi communities in India, the land is not an abstract resource but a symbiotic lifeworld.

The soil still remembers, still speaks in voices the powerful ignore.

The surface of the landscape in reality is a palimpsest of contested meanings.

Outlook Anniversary Issue: Known And Unknown Worlds Beyond The Visible

To engage with landscape today is to reject superficial beauty and cultivate inner vision — a deliberate peeling back of layers to reveal the stories of struggle embedded within.

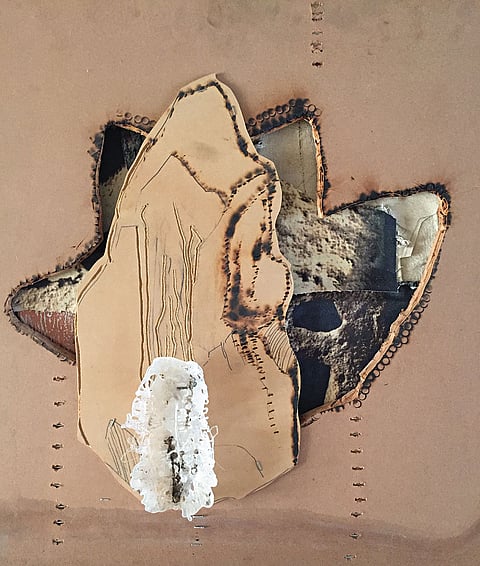

In an era where the gaze upon landscape has commodified into picture postcards with pristine beauty—rolling hills, serene rivers, untouched forests—the true essence of the earth demands a radical shift. Landscape is no longer merely a concept of aesthetic pleasure, a passive backdrop for contemplation or leisure. Instead, it requires an inner vision, a penetrating gaze that unearths the complex layers of stories buried beneath its surface. These are narratives of trauma, resistance, memory and survival, etched into the soil by centuries of human and ecological strife. I am not a mere observer but a cultivator of archives—re-animating and re-cultivating them repeatedly to forge new historiographies that challenge dominant erasures and reclaim subaltern truths.

The surface of the landscape in reality is a palimpsest of contested meanings. It is a “nexus” where history, identity, power and resistance intersect in profound, often violent ways. For Adivasi communities in India, the land is not an abstract resource but a symbiotic lifeworld—a living entity that sustains cosmologies, knowledge systems and communal existence. This harmony is perpetually unsettled by colonial legacies and contemporary dispossessions: forests razed for mining corridors, rivers dammed for “development,” hills scarred by industrial greed. These acts inflict double violence—physical on the earth and ontological on its people—turning the soil into a traumatised archive of wounds.

Rabindranath Tagore envisioned education and creativity under open skies, free from colonial hegemonies, as a means of world-making through harmony with nature. But in today’s hyper-digital age of fractured selves and ecological collapse, this vision must evolve. Propelled by the fierce ethical clarity of writer Mahasweta Devi, whose works insist that land is the living body of the dispossessed. She lived among DE-notified Tribes—the Sabars, Lodhas and Santhals—documenting atrocities, fighting legal battles, and weaving rage into literature. Her warning, “The village is no longer the same as before.” That echoes louder in 2025 amid green grabs and carbon schemes that mask ongoing exploitation.

To engage with landscape today is to reject superficial beauty and cultivate inner vision—a deliberate peeling back of layers to reveal the stories of struggle embedded within.

These fleeting images are not static objects; they decay and dissolve, honouring the subaltern right to opacity.

Tagore granted the right to imagine new worlds; Devi imposed the duty to stand with those whose worlds are vanishing.

In ‘Song of the Soil’, the landscape — known and unknown — becomes a c for survival and sovereignty. It transcends beauty to demand inner vision, urging us to listen to the earth’s layered whispers. The soil still remembers, still speaks in voices the powerful ignore. That’s the known and unknown and this isn’t an elsewhere place but our very own.

Samit Das specialises in painting, interactive artworks & artists’ books

This article appeared as 'Known And Unknown' in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘Party is Elsewhere’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.