The departing sun ignites the lushly carved masjids, maqbaras and mandirs set in the sere landscape of Champaner. In that last-gasp light, these ancient monuments achieve a luminosity—golden yellow, tinged with red—that recalls the colours of the champak flower. Poets and artists have long mused that this was how the medieval capital of Gujarat was named; but the nomenclature means little to the inexorable stream of pilgrims who tread the patha up Pavagadh hill, southwest of the town. Their goal, as linear as their climb, is to visit the Hindu and Jain temples at the summit.

“Eighty percent of the pilgrims don’t even know there is a Champaner, they only know Pavagadh,” says Manoj Joshi, a member of the Vadodara-based Heritage Trust which campaigned for more than 20 years to have the ‘forgotten city’ of Champaner-Pavagadh designated a World Heritage Site—a goal that was realised in July 2004. The devotees make a circuit of the Lakulisha and Kalikamata temples, which are the oldest surviving monuments of the area, and descend. “Darshan kar diye, chal diye,” says Joshi, my guide on the tour of this historical settlement.

His dismissive attitude towards the pilgrims bewilders me at first. Standing on the patha at the Machi plateau, halfway up Pavagadh, I survey the rash of kiosks selling farsan, the heaps of gold-edged cloth and the scraggly donkeys—all generic Temple Town to my mind—and am ready to leave the hill myself. Why would anyone want to stay?

I ask as much, and Joshi scuttles off the patha and asks me to follow. I do as instructed, ducking under thorny branches. The undefined pathway through scrub and teak trees opens onto a natural terrace which overlooks the monuments and lakes of the Champaner plains. Then I gasp. At the edge of the terrace, I detect a partially ruined structure projecting over the precipitous Vishwamitri gorge and descending in multiple tiers almost to the base through a flight of stairs that ends in a tower.

“No one knows this is here,” Joshi says, adding that Khapra Zaveri no Mahal has no foundation and was built directly on the rocks over the ravine. The pilgrims leave, he explains, oblivious to the fabulous architectural remnants—of a royal mint, noblemen’s havelis, army chowkis and the splendid seven-ringed fort walls—that stud Pavagadh but require a five-minute detour from the stone patha.

Joshi nimbly climbs down the dizzying stairs of Khapra Zaveri to its tower, and I follow with some hesitation. We find an animal skeleton—a monkey brought in by a wild cat, he speculates—in the lone room of the tower. Local historians say that the structure with its multiple covered pavilions may have served as a machan for shooting panthers and leopards, which come to the Vishwamitri waterfalls even today. The strategic location, with unimpeded views of the surrounding environs, suggests it may have also served as watchtower and barracks. Today the panorama includes hills pockmarked with craters—the handiwork of 140 stone quarries whose activities were banned in 1997 by the Supreme Court, following a Heritage Trust petition.

On our way back to the top, Joshi recounts that conservation architects had believed until three years ago that Khapra Zaveri had two viewing pavilions. Then the Heritage Trust discovered 117 vintage photographs of Champaner-Pavagadh at the British Museum in London, one of which showed the structure had had three distinct pavilions. The story of the ‘forgotten city’—and its 114 ruined monuments in a six-sq-km radius—has required painstaking excavation, both literally by archaeologists of MS University in Vadodara and metaphorically through study of old records, inscriptions and manuscripts.

Champaner, it emerged, has been continually settled since prehistoric times. In 1515 AD, the Portuguese traveller Duarte Barboza described it as the most delightful place on earth, a Muslim settlement of Persian-inspired royal gardens and ornate water structures such as stepwells. But a century later, the Arab historian Sikandar-bin-Manzhu recorded that the town was already in ruins during Jehangir’s reign. Many buildings were buried under dense vegetation in subsequent centuries. An excavation in the 1970s unearthed almost 2,000 buildings including the meticulously designed nobleman’s residence, Amir ki Manzil, which has rooms with open water channels, a terrace garden, servants’ quarters and stables.

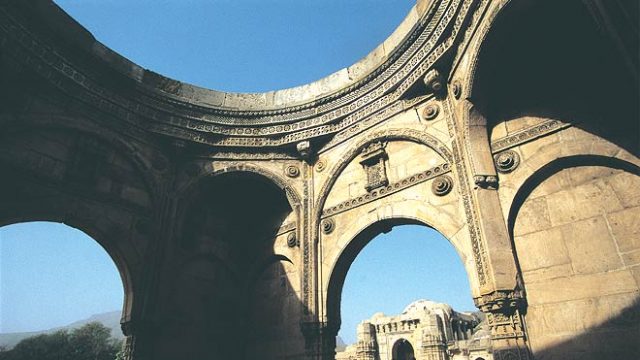

Perhaps the most ambitious of the constructions here is the seven rings of fortifications—with an ingenious network of gateways, watchtowers, garrisons and barracks—that rise up the hill. Joshi and I walk along the labyrinthine fort walls from Khapra Zaveri until we come to the Sat Kaman, a series of seven arches (one has fallen) built of local yellow sandstone. The arches support high walls resembling a bastion, which contain large openings that were perhaps used to dispense gun powder. Behind Atak Killa, one of the fort walls, is a curious sight—73 trapezoidal structures of parallel walls. Their purpose seems obscure until Joshi explains they were catapults used to hurl immense rocks at unsuspecting enemy soldiers.

Built by the Khichi Chauhan Rajputs in the 13th century, the stone-and-brick fort walls secured the Hindu kingdom of Pavagadh against more than a dozen attacks by the Gujarat Sultans throughout the 15th century. In 1482, Mahmud Begarha established his sovereignty over the settlement sprawled at the base of Pavagadh; but it took him another two years to capture the hill itself. “The reason (the Sultans) couldn’t conquer Pavagadh was the forts,” says Joshi, adding it was considered so impregnable that a bird caught within could not get out.

Begarha established his capital at Champaner-Pavagadh in 1484, and renamed it Shahr-i-Mukarram. Intensive construction of civil and military structures began, lasting almost half a century. The most significant contribution of the Sultanate rulers to the town’s architectural heritage are the mosques which blended Islamic ideals with the artistry of Hindu craftsmen. At the Shahi Masjid, a private mosque for the royal family, Joshi points out that the outer walls feature stone jharokas with perforated jaali or latticework—a typically Hindu architectural detail. In the prayer hall, five mihrabs, or carved niches, are adorned with motifs derived from Rajput havelis. The carved friezes on the ceiling include the Jain motif of the kalpavriksha or tree of life.

The royal mosque is housed within the Hissar-i-Khas or Royal Enclosure, which also had palaces, gardens and baradaris or pleasure pavilions. Begarha had invited a Persian landscapist called Khorasanni to lay out the royal garden within the Hissar-i-Khas. The garden is now in ruins, but the remnants of water channels can still be seen.

We drive out through another gate of the Royal Enclosure and head towards Vada Talav or the Talab-i-Imad-ul-Mulk, the largest lake on the Champaner plains. The scarcity of water forced the sultans to employ various means to store monsoon and underground water. The Talab-i-Imad-ul-Mulk was created by damming a depression and diverting water from rivulets and runoff into it. A pleasure pavilion, locally known as kabutarkhana, stands on the edge of the lake, with the Pavagadh hill forming an impressive backdrop. “This was known as the Hawa Mahal or the Jal Mahal,” Joshi says. “Begarha came here to relax.” Almost five centuries after it was built, I savour the view from the arched windows and feel my spirit merge with the fishermen wading chest deep in the lake, the herons gliding over its polished green surface and the water buffalo slumbering on its bank.

The information

Getting there: Vadodara (Baroda) is the nearest railway station and airport to Champaner-Pavagadh, located 50km away. Both Indian Airlines and Jet Airways have daily flights from Delhi and Mumbai to Vadodara. From Vadodara, there are frequent and good bus services to Champaner; Gujarat State Transport buses take 1hr30min.

Where to stay: Accommodation at the site isrestricted to Gujarat Tourism’s38-room Hotel Champaner (www.gujarattourism.com) on the hill of Pavagadh. Alternatively, stay in Vadodara which has a range of accommodation on offer.

Guides: Local tour guides are plentiful at Champaner-Pavagadh. An English-speaking guide can be arranged by contacting the manager of Hotel Champaner.

What else to see & do: Other highlights of Champaner-Pavagadh include the major festival honouring the goddess Mahakali, held in March/April, at the foot of Pavagadh. The Ratanmahal Sanctuary, 90km away, is home to the sloth bear, as well as leopards, nilgai, wild boars and Indian gazelle.

When to visit: The best time to visit Champaner-Pavagadh is October to December and April to mid-June.