Pollution sources vary sharply by season: dust dominates summer air, while winter pollution is driven overwhelmingly (85–94%) by combustion sources such as vehicles, industry and biomass burning

Farm fires in Punjab and Haryana, driven by short crop cycles and economic pressures, significantly spike Delhi’s pollution.

Converting agricultural residue into biomass pellets and biochar can cut pollution, sequester carbon, and reduce reliance on coal

Stubble Burning: Can Delhi Turn a Challenge Into An Opportunity?

Delhi consistently ranks among the world’s most polluted cities, posing a severe public health threat to over 30 million residents and shortening life expectancy by up to 12 years.

Delhi, India’s national capital, arguably has the worst air quality in the world. According to the World’s Most Polluted Cities report by IQ Air, it ranked second over the past decade. Each winter, heavy smog and multiple pollution sources push the Air Quality Index (AQI) beyond 500, equivalent to smoking 33–50 cigarettes a day. In 2020 alone, this pollution was linked to around 54,000 deaths and economic losses of $8.1 billion. Recent studies warn that the 30 million people living in the National Capital Region could lose up to 12 years of life expectancy due to prolonged exposure to toxic air.

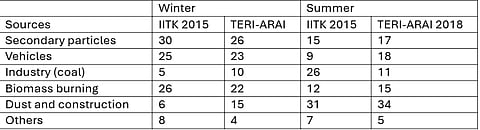

Studies show clear seasonal shifts in Delhi’s pollution sources. In summer, dust accounts for around 31–34 per cent of pollution, but this falls to 6–15 per cent in winter. During winter, combustion sources, such as vehicles, industry and biomass burning, dominate, contributing 85–94 per cent of overall pollution.

To curb peak pollution during periods like winter and Diwali, authorities impose measures including odd–even traffic rules, construction bans to control dust, and schemes to discourage farm residue burning through in-situ management. Despite these efforts, biomass burning remains a major concern, peaking at around 26 per cent in winter and 22 per cent in summer, even under strict regulations. (Table 1).

Changes in legislation in 2009 left farmers with just a 25-day window between harvesting rice and sowing wheat. Burning crop residue is the quickest and cheapest way to clear fields, but this practice, known as stubble burning, has become a major contributor to Delhi’s winter air pollution. Although banned in 2015, it continues, albeit at lower levels, and has previously accounted for up to 50 per cent of early winter pollution.

When farmers in Punjab and Haryana burn stubble, air quality in Delhi deteriorates sharply. On 16 October, the Supreme Court criticised both states for poor enforcement. While Punjab cut stubble fires by 42.8 per cent between 2021 and 2024, Haryana recorded a worrying 222.6 per cent increase over a similar period, worsening winter smog.

A sustainable alternative lies in converting surplus agricultural biomass into bioenergy. Using crop residue to produce clean energy can reduce pollution while delivering wider environmental and social benefits across air, water and land.

Biomass pellets are made from compressed organic matter, primarily agricultural residues of primarily rice husk and wheat straws. When these are converted into pallets, it becomes a non-polluting or even significantly lower polluting form of fuel than traditional residue burning.

Biochar or biological charcoal is produced naturally in the forest over the years when the vegetation is left to smolder (flameless combustion) in layers on the forest floor following a forest fire. Today, with the help of modern technology, it is made with the help of pyrolysis in a biochar klin. The biomass of different kinds is slowly baked until it becomes a carbon-rich char. [1] Pyrolysis, unlike combustion, traps carbon in solid biochar instead of releasing CO₂. For example, one ton of biochar sequesters carbon equivalent to 3.6 tons of CO₂ that would otherwise emit through natural decay. This makes the use of bioenergy a great way for carbon sequestration as well.

India's bioenergy sector faces critical challenges in scaling up, despite its renewable energy potential. The seasonal availability of agricultural residues creates unstable feedstock supplies, while high transportation costs of 20-30 per cent make biomass less competitive against subsidized fossil fuels. Quality inconsistency in biomass pellets, due to lack of uniform standards, undermines market confidence even with existing policies like SATAT[2].

Financial viability remains difficult with bioenergy costs of ₹5-7/kWh competing against cheaper coal and solar. Key solutions include establishing farm-level processing units, enforcing quality standards, and implementing financial mechanisms like carbon pricing to boost competitiveness. Addressing these supply chain, quality and financial barriers through coordinated action is essential for sector growth.[3]

Bioenergy offers a viable alternative to India’s highly carbon-intensive coal. Organisations such as NTPC are already using biomass pellets to cut emissions from coal-fired power plants. With rapid growth in green energy and stronger climate commitments under India’s NDCs, bioenergy could play a key role in the country’s renewable energy future if developed sustainably.