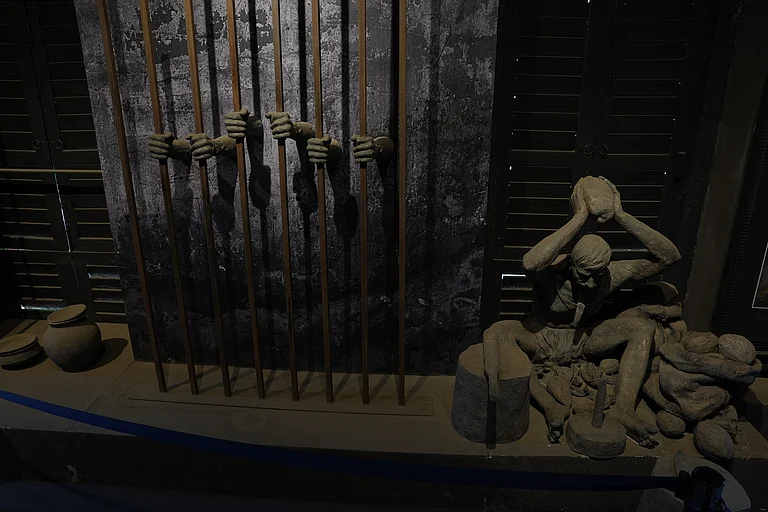

Kobad Ghandy was incarcerated for a decade under UAPA.

His Prison memoir 'Fractured Freedom' encompasses the journey of an under trial political prisoner and his partner Anuradha Shanbhag's political activism.

This lucid memoir explores what Justice and freedom mean for political activists.

Kobad Ghandy’s ‘Fractured Freedom’

This prison memoir, published after Ghandy was released on bail after ten years in prison, looks back at his and his partner’s lives and the search for justice.

Grassroots

In 1982 we finally decided to shift to Nagpur which was then the heart of the Dalit movement. The entire Vidarbha region was also where extensive mining, particularly coal, was taking place.

Jyoti continues:

It was time for Anu to grow into a successful academic, the type who writes books and attends international seminars. Instead, in 1982, she left the life she loved to work in Nagpur. The wretched conditions of contract workers in the new industrial areas near Nagpur and of Adivasis in the forests of Chandrapur had to be challenged. Committed cadres were needed. In her subsequent trips to Mumbai, Anu never complained about the drastic change in her life: cycling to work under the relentless Nagpur sun; living in the city’s Dalit area, the mention of which drew shudders from Nagpur’s elite; then moving to backward Chandrapur. in Marxist study circles, “declassing oneself” is quite a buzzword. From Mumbai’s Leftists, only Anu and her husband Kobad, both lovers of the good life, actually did so.

In truth, we never considered it a sacrifice, just a part of life as a true revolutionary. It is true the places we took on rent were simple and so was the food.

We knew no one in Nagpur when we moved there. Anu got a job as a postgraduate lecturer in Nagpur university and I got a temporary writing job in the Sunday edition of Hitvada, a reputed english daily, which had supported the freedom struggle in the pre-independence days. With the help of a socialist, Nagesh Chaudhary, we were able to find a reasonably priced accommodation to rent in Laxmi Nagar. The place had a leaky roof and whenever it would rain, we would spend the night removing buckets of water.

As the main field of activities was amongst the Dalits, within a few years we shifted to Maharashtra’s biggest Dalit basti, Indora.

In a 2009 article for Open magazine, Rahul Pandita wrote about those times, saying:

[they] rented two small rooms at the house of a postal department employee, Khushaal Chinchikhede. “there was absolutely nothing in their house except two trunks full of books and a mud pitcher,” he says. Anuradha also worked as part-time lecturer in Nagpur university. Later, Kobad would also come to live there. Both would be out till midnight. Anuradha used a rundown cycle to commute, and it was later at the insistence of other activists that Kobad bought a TVS Champ moped... Indora was notorious for its rowdies. “No taxi or autorickshaw driver would dare venture inside Indora,” says Anil Borkar, who grew up in Indora. But Anuradha was unfazed. “she would pass though the basti at midnight, all alone on a cycle,” remembers Borkar.

Indora was such a dreaded place that middle-class people were scared to go to that area after dark due to the impression that it was a nest of crime and were shocked to find we were living there. such impressions are easily created in impoverished Dalit and Muslim localities because of inbuilt biases and a certain amount of petty theft due to extreme poverty that gets magnified.

A typical day in Nagpur would start with Anu cycling/ busing to university, over 15 kilometre away, leaving early in the morning after having breakfast. i would do some of the cleaning up of the rooms and then meet the Dalit members of the community in our basti.

Working amongst Dalits we hoped to arouse them not to accept their existing status that their religion sanctified. We encouraged them to stand up for their rights and study both Ambedkar and Marx. Ambedkar would give deeper insight into the caste issue, while Marxism would keep them away from identity politics and help them unite with other oppressed, even from other castes. The two ideologies would show them the path as to whom to target and whom to ally with – i.e. target Brahminism (the ideology) and those who propounded it and not all upper castes; on the contrary one needed to educate those from the other castes (like the OBCs and even upper castes) to drop their casteist feelings. We would encourage inter-caste love marriages to help facilitate this unity. the point was not to consolidate caste, even scheduled Caste sentiments, but destroy the caste system from its roots. One had to counter identity politics amongst Dalits which the Dalit political leaders promoted for their vote-banks.

Many of the youth of Indora were attracted to our views and joined our organisations of student/youth, especially the cultural organisation, Aavhan. Jyoti, the daughter of Khushal Chinchkhede (the postal employee whose first floor we rented), and her friend who stayed across the road, Jyotsna, were active in our organisation.

(Excerpted from Kobad Ghandy’s ‘Fractured Freedom: A Prison Memoir’ with permission from the Roli Books)