Amitava Kumar discusses how Indian trains reveal the invisible lives of migrant workers and the social realities of the country.

He reflects on Bihar, Patna, migration, nostalgia, and how memory shapes both literature and political thought.

Kumar explains his writing process, grief, identity, and why carrying notebooks is essential to being a writer.

“You Are Not A Writer If You don’t Carry A Notebook”

Writer and journalist Amitava Kumar was in our studio recently, carrying five different notebooks meant for five different purposes. “That’s a basic every writer must have,” he said.

In a long, free-wheeling conversation with editor Chinki Sinha, he talks about his latest book—The Social Life of Indian Trains—his writing process, his roots, identity, his love for Bihar, the in-between places where he resides and what nostalgia means to him. Edited excerpts from our new podcast series—'Our Lovely Friends’.

Very few writers have written about Bihar. You are one of them. In fact, that was our first point of connection. You have written A Matter of Rats, which is a biography of Patna. I remember reading Husband of a Fanatic when I was in college and wanted to meet you since then. In fact, I first met you at the New Jersey airport baggage counter …

… you didn't want to talk to me, but yes!

I didn’t know how to react! But we have kept in touch since then. You have also written a lot for Outlook…

To write for Outlook and do the book reviews was a great dream of mine. Vinod Mehta was the editor when started. I've always cherished Outlook.

Let’s talk about your new book—The Social Life of Indian Trains. My first memories include taking a train out of Bihar. The flights were out of reach and the trains were eternally late. So how did you come up with this unique idea?

The commission came from Aleph. David (Davidar) asked me if I wanted to write a longer book. He read the piece I had written for The New Yorker about my three-day journey on the Himsagar Express. I got on it in Kashmir and I travelled across the length of India, from the northernmost station in India to the southernmost station in India, to Kanyakumari. There is a documentary named I am 20, which came out in 1967. India was 20 years old then, people in the film were also 20. One guy in the film says he would like to go up and down the country with a notebook in his hand. I wanted to do the same; ask people on the train—where is India going? Where are you going? What are you doing in your life? That account was published in The New Yorker. David said maybe you could do a book for us.

You keep going back to Bihar. What is Patna to you? There was a piece that I was reading in The New Yorker by James Wood, where he talks about A House for Mr. Biswas by V.S. Naipaul. There's a beautiful line—"historical time tells us that Mr Biswas’s life was not worth writing. Novelistic time is more forgiving”. And then he talks about your book—My Beloved Life. How do you look at places, people, novel, history?

While my parents were alive—my father died two years ago—Patna was the place of return. I went around the world, but that’s where I would go back to. After my parents died, I think I lost that connection.

Coming to Naipaul's book, you know, people from UP, Bihar immigrated and went as indentured labourers to Trinidad. There are children of these indentured labourers, who are poor. This man, Mr Biswas, doesn't have a house. By the time the book ends, you are reminded of the line that Wood says—what would it have been like if they had been unaccommodated, unhoused? It’s good to have a house to return to. Perhaps for Wood, the idea of home is important in the novel. That is what Patna is to me.

I have been abroad for 40 years. India is where my material is, but the real home is in language. To find a home in language and a language of one's own devising, or maybe a shared language, but a language that is so particular that it makes you think that you are at home.

You wrote a sentence in one of your books that I have quoted many times—my one place is home, the other is the world. It contains a lot of conflict, sadness and hope…

When I talk to someone like you, I feel that I know so little about this country.

I think you know a lot!

I asked you about so many friends, and you knew so many secrets about them, which I have no idea about!

You also knew two-three secrets!

What one needs is more and more intimacy with friends to be a little bit more anchored in the lived reality of our friends.

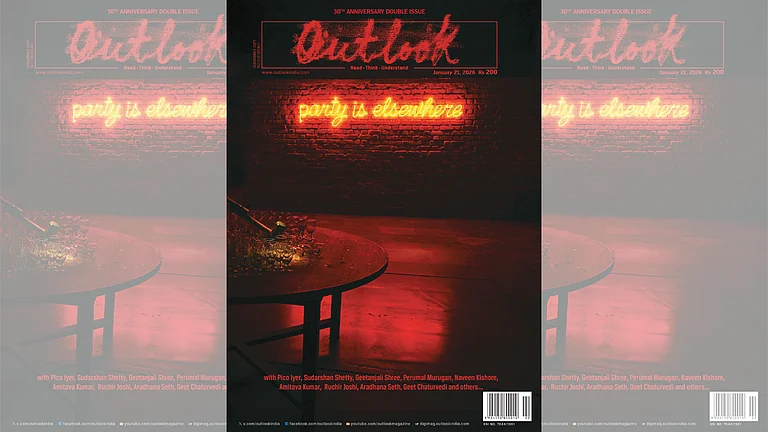

You wrote a very lovely piece for our 30-year anniversary issue, and that too in one night. This is what friendship is. The idea was a very complex one—to talk about landscapes, which are fictional, and then how to connect the reality with it. Cities also exist in memory, right? The Patna you left behind and the Patna that is now are very different. As a writer, how do you look at this?

I was watching a BBC documentary, in which a man goes to Patna and talks about its glorious past; he compares it to ancient Rome. Any common person watching it would have felt proud. Maybe I did too. But that pride was not important for me; the landscape was more important because I connected it to the declining health of my parents. That made it real for me. What stuck like a knife in my heart was—how is their health? When will I have to come back? What will be the news that will bring me back? So, you inhabit a landscape of fear and anticipation—sometimes with hope and optimism; that’s India for me.

In 2014-15, you wrote a long and beautiful note to me from in between flights. That was the time when your mom passed away. Soon after, I received another note like that from our actor friend Vinay Pathak, who lost his father and he was also on a journey. I don't know what is it about people from Bihar who are writing while travelling!

This incessant migration is a part of our reality! Why did you and I move out of Patna? Because the institutions that were there for our parents, something that they were proud of, were not available to us. You have written about this. You call Patna ‘a city of eternal waiting’.

We, Biharis, are so unaccounted for. Look at the migrant labourers; what happened to them during the pandemic is so heartbreaking. You have written about these people in your books...

Writing offers you relief. Let me tell you a story from my book. I met a migrant labourer from Bihar in the train and told him I wanted to ask him some questions. He showed me his hand. There were two numbers written on it. He said, before we start, please write down these numbers for me. I had a notebook, so I quickly noted down the numbers and gave the piece of paper to him. It was probably his contractor’s number or something. He was travelling across the country and going to Andhra Pradesh and his only connection to that place was these two numbers. I remain struck by his courage, by his ambition. He had nothing but hope; a slender thread of optimism. I then asked him what would happen if these trains do not take off. He said: “Desh ruk jayega (the country will come to a halt). That is a statement about these unaccounted lives, these people who are invisible. I'm privileged to travel and find a great resource in trying to attend to the realities of these lives, which would otherwise go unnoticed...

I think literature shapes a lot of your political thought. At Outlook, our idea is to be more inclusive. Why shouldn't journalism include any of this? You call yourself a journalist and you are also a writer. How do you navigate both the worlds? How does one feed the other?

Say, you're an Indian walking on the streets of New York City. If you say something to a passerby in Hindi, that person will mostly say, this is America, please speak in English. I should be able to tell him: “No. This is also a part of my identity.” As an immigrant, you are made up of different languages and we have different realities. All human beings are made of different parts. I feel one should not be trapped by the knowledge of a particular language. People can be photographers, journalists or poets despite that.

You also paint…

Yes, I started during the pandemic. There is a poem by Faiz—kuch ishq kiya, kuch kaam kiya, aur aakhir me tang aake humne dono ko adura chchod diya.

Painting is a very interesting approach. Your work is very inclusive. We are dealing with so much censorship. I think one of the ways to counter that is to use as many resources as we can. My next question is, when we go on field, sometimes we see very disturbing thigs. People say as journalists, we get used to it. I want to know what is your process of writing. Writing is therapeutic, but when you encounter grief or sadness, how do you process that?

I believe, you are not a writer if you are not carrying notebooks. I am carrying five notebooks right now—a small pocket diary, a bigger one to write long notes, a morning journal in which I make a small drawing and make a note of things to do, a five-year diary in which, for the past five years, I have been noting down things that I do on that particular date and a notebook to note down long conversations. Writing is your entry into the world of the process of creation. If journalism is the first draft of history, a journal is the first draft of literature.

Coming to how I deal with sadness or grief while writing, I am reminded of an incident. There was a white South African writer—Breyten Breytenbach. He was jailed during apartheid because he was involved in struggles to free the blacks. After he came out, a journalist asked him: “How did you survive prison?” To which he replied: “I did not survive”. I don’t think we survive. We perform our duty by being sensitive to, alert to, attentive to all the sorrows of the world. I don't think you ever escape.

The world that we are living in right now is all about either here or moving on. That in-between space is what the writers and artists inhabit.

Yes. There is no nirvana or salvation for us. We are rooted somewhere, but we are also in transit.

You have been abroad for 40 years, but your subject matter remains here. You write about and connect with a place like Patna, but you live in New York. How do you look at identity?

There is a cemetery close to my place in New York. There is a grave of an Indian lady named Anandi Gopal Joshi. She travelled to New York in 1883 with the help of a family who sponsored her education. She graduated as a Doctor of Medicine from a college in Pennsylvania. Ill health forced her to return to India and she died of tuberculosis at the age of 22. The family, who sponsored her education, buried her ashes in the New York crematorium. There is also a crater named after her on Planet Venue. The point I am trying to make is, you may have small beginnings, but you can end up in antariksha (space). The answer to your question about identity lies in travel—where your “roots” are and what your “routes” are.

Where do you feel at home then?

My village in Champaran in Bihar is what comes to my mind when I think of home. But when I think about my actual home, I return to the pages of my books, the written words. It helps me connect and breathe.

Sometimes, I feel homeless. Do you feel that way?

As a writer, I am very much influenced by Naipaul. He came looking for his home and wrote An Area of Darkness, based on his great disappointment with the land. I thought I could do a journey in reverse. I want to share my experience of my journey to Trinidad. There is a documentary that I made named Pure Chutney. I visited Trinidad to interview people who had descended from the slaves and merchants who migrated there from India during the colonial era. Most of them have Spanish surnames, but vestiges of the old culture survive in their customs, their ceremonies, and their fond preoccupation with the motherland. I am always interested in travel that has produced a sense of both, of difference and something that has remained as a residual of your past. For example, one quick instance of that experience. In Trinidad and the Caribbean, Indian music and black music mingled to produce what is now called chutney music. How did it come into being? Conservative Indian parents were not interested in their daughters being exposed to black music and going to parties. They wanted to police the sexuality of their daughters. So, this music was produced to play at Indian weddings, events and festivals. It became both a way of mixing but also a way of controlling identity. So, I think, my job as a writer is to track these histories. This is where migrant writers need to invest their energies. Not so much in nostalgia, though there can be affection; not so much in celebrating only solitude, though there can be that too; but instead, in tracking what kinds of changes have brought us to that place. How does someone like Mamdani arise?

How do you look at yourself as an Indian?

Whenever I cross this particular temple in Patna, people stop me and ask: “Sir, dollar bechna hai? (Do you want to sell dollars?). Though I am an Indian, those people know that I live abroad. When I step into a public space in England or America, I'm seen as an Indian. I don’t know where I belong. I am somewhere in between. I am exploring how to define myself. I feel that when I grasp a language and I'm able to produce a story or a narrative, that is where my home is. When I see Indians doing something wonderful, I feel proud. But when I see Indians disrespecting someone or indulging in violence, I feel like protesting.

How do you protest?

Mostly through my writing. Sometimes people say I have not written enough about Palestine. I am a writer. I don’t think my main job is to join a procession or to write a petition. My job is to write something that has not been said before; to do something differently to address the complexity of a situation and while doing so, should I use fiction or journalism?

I recently shared something about Zadie Smith; something that she wrote about being a woman and someone commented: “But have you read her views on Palestine?” The cancel culture is a bit much...

You may dislike something that you haven't written. Even among friends, there should be a certain kind of acknowledgement of a range of complexity and difference. Life has to be rich and messy.

A lot of people have talked about memory as a landscape or as an imagination. You rely heavily on memory. What is nostalgia to you?

There is an essay by Joan Didion in which she writes about her youth when she had to take a train to Berkeley from Sacramento every day. She writes about the rancidity of butter on the toast that she ate on the train. Fifty years ago, when I used to travel from my village to Patna on a steamer, while crossing the Ganga, they used to sell toasts, toasted on charcoal. They used to put butter and green chilies on it. I still remember the taste of that butter. That is nostalgia. But there is a catch about nostalgia. In diaspora, the soft emotion of nostalgia has been turned into the hard emotion of fundamentalism. You are nostalgic for an old India, but you are using that affection or that imagined affection to turn into something brutal and violent against those who represent difference. This transferred memory is often delusional. It’s a challenge to have an effective sense of the past but yet be skeptical of it.

How do you do it?

I often actually do not. I succumb to nostalgia. When I think about the woman I loved while I was in Hindu Collage, I am shaken to my core. We used to write many letters back then. She is now a well-known academic. Many years later, I wrote to her again, saying I would love to get together again. That meeting has not happened so far, but I will wait!

I feel Biharis are experts at waiting!

We are experts at waiting because we are connoisseurs of suffering.

Talking about the recent Bihar elections, or the whole pandemic experience, there emerged a sense that Biharis are not ambitious enough; that we are happy with whatever little we have.

During Covid, a girl crossed the whole breadth of the country with her father on a bicycle. There is another story where a migrant worker left a note saying: “Please forgive me. I am stealing your bicycle. I have a child who cannot walk”. These are acts of wonderful humanity that come from a place of having so little and yet having so much emotion, sympathy or imagination to be able to say something that is so revealing. I have contempt for our political leaders because they offer people so little. They trade these emotions with votes. It leads to their prosperity but leaves the masses impoverished.

Why do we let go so easily?

You are forgetting that Bihar has been the site of repeated revolutions and agitations. People do rise up. We always say that it is the land of the Buddha. He endured suffering and ended up enlightened. Maybe we have internalised that!