Torrential Reign

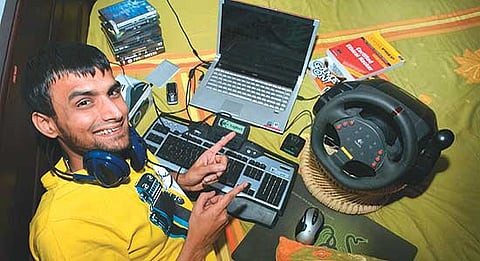

Young Indians are riding the surf with free downloads on the net

- Fuelled by cheap broadband, 30-40 million Indians—a large chunk of the internet population—is downloading and sharing music, software, films, TV shows, games

- Google data shows a 2050% growth in searches for “extra torrent movies”, 700% growth for “songs.pk free download” and 900% for “Hollywood blue films” in the past 12 months

- Between 19 and 35 years, most are working males who see free content as an undeniable fact of life

- Using peer-to-peer networks, Indians now largest downloaders of illegal content in Asia, fourth largest in the world

- Viewing streaming content like YouTube videos has overtaken social networking in popularity

***

Yes, only an hour or two, and then his computer takes over.

Subir is one of the 30-40 million young Indians who are staying up nights trawling the internet’s hottest fashion statement: file-sharing websites. BitTorrent, desitorrent, limewire, KaZaa, iMesh, DCTorrents, SoulSeek, Gnutella, Overnet, Morpheus and hundreds of other such oddly-named websites that are nothing but millions of computers exchanging large quantities of data. They are such a rage that in two January 2010 reports, India was declared the fourth-largest illegal downloader of content after the US, UK and Canada. The reports were commissioned by a lobby group for the six major Hollywood studios in India, one of the many businesses that say they are being harmed by the download culture sweeping across India.

To see it for yourself, you just have to visit a cyber cafe, or steal a glance at your neighbour’s computer. Chances are that you will find at least a couple of downloads in progress. It could well be a software package, a music video, computer games, e-books or the latest Hollywood or Bollywood blockbuster. Almost everything you want is online, and available for download. “Yes, they are downloading away,” says Mahesh Murthy, who heads search-marketing firm Pinstorm. “In just the last one year, there has been a 60 per cent increase in people searching for (free) downloads. Largely, the surge is fuelled by the young and the very young.”

Sure, as any geek will testify, downloading from the net has always been around, from news groups a long while ago to irc to Napster, which ultimately got shut down. But over the past couple of years, fuelled by cheap broadband and the ease of use of new file-sharing tools like BitTorrent, downloading has gone mainstream in India. To understand where the real demand for downloads is, imagine a young, working professional in a city like Raipur or Vijayawada, where shopping malls and multiplexes are relatively rare and internet access is both a novelty and a much-needed window to the world.

A torrent uses a file that can be split into smaller pieces and tracked across many computers. Each such torrent filename usually ends in “.torrent”. It's useful to transport large files, such as movies, games or software, across the internet.

- Find a torrent client website, such as BitTorrent, uTorrent and many more. Download the torrent client appropriate for your computer.

- Go to a torrent file-hosting website, such as The Pirate Bay, DesiTorrents, Bwtorrents, DCTorrents, Idesir or ImTorrents, to search for files you want to download.

- Download the torrent file by choosing “open this file” when the option shows up. A song takes a few minutes; a movie could take up to two days to download.

- Have at least 512 MB spare ram, 1 GHz CPU. For optimal results, use 512-kbps broadband connection. Other must-haves: adequate disk space, anti-virus software.

- To play such downloaded movie files on your TV, get a portable hard disk with a media player. You can also burn a DVD of the media file and play it.

- While "torrents", as a means to distribute content online, are perfectly legal, if you distribute content that does not belong to you, you may be violating copyright law.

***

| Activity | % of all Internet users |

| Search/Buy travel product | 84% |

| Stream music online | 49% |

| Download music | 48% |

| Online games | 43% |

| Video sharing | 33% |

| Source: JuxtConsult, Feb '09 | |

For businesses perhaps, all this file-sharing business is one enormous headache. But for many others, the pirate websites and file-sharing are just a sign of India’s internet story coming of age. “India definitely has a new breed of internet users, and they are progressively more tech-savvy, increasingly young, upwardly mobile, and living in smaller towns and cities,” agrees Savio D’Souza, the secretary general of the Indian Music Industry (imi). Earlier this year, the Internet Service Providers’ Association of India found 6.9 lakh songs adrift on 113 pirate websites. Of course, D’Souza says, the music industry is contemplating strict action, including shutting down the pirate sites.

But what would be the point? When one pirate falls, hundreds rise to take its place. Besides, there are also websites outside India, such as songs.pk, a Pakistani site hosting thousands of Indian songs that Indians adore. Whether surfing for porn or hunting for music hits, the online activities of Indians are so varied that they are increasingly difficult to monitor and control. To boot, their online ethic is increasingly permissive: the new Indian internet user will sidestep the rules as long as he gets his way. He might occasionally look over his shoulder to check if the law is watching, and then resume the download, because it isn’t.

Kasturi Rangan, a Hyderabad-based game consultant, typifies this clarity of thinking. “Think about it, if all that we do every day wasn’t as free as it is now, most of us would be illiterate in computer technology,” says the 25-year-old who won’t say where from he shares files online. That’s typical as youngsters such as him are not just cagey about being banned but also that file-sharing websites, whether free or paid-for, are so much in demand that subscriptions are often closed to new members, or are only by invitation.

It is the thought of thousands like Rangan, with their new-fangled ideas on access to information, that is giving the content industry sleepless nights. Rajiv Dalal, managing director, Motion Picture Dist Association, says that forensic examination shows nearly every Hindi title is camcorded within the first few days of its release in theatres. It’s just that online file-sharers have taken up where physical piracy left off.

And it’s not just the business moghuls who are worried at the trend. Tamil superstar D. Sarath Kumar actually chased two video pirates this January through the narrow lanes of Vyasarpadi, a city slum, for over a kilometre—and no, it was not a shoot for some film. He caught one and handed him over to the trailing police cars. Kumar’s heroics led the cops to a den of pirates no larger than Salman Khan’s shirt closet. Inside, 10 men were found making copies of his new movie, Jaggubhai. The film hadn’t even made it to the theatres, but it was already on the net.

Of course, finding “innovative strategies to make money from content online” is the holy grail for the industry. But then people accustomed to getting stuff for free are unlikely to pay for it now. “To an extent, industry is responsible for free downloads,” says Sanjay Tiwari, director, JuxtConsult. “What is the music or film industry’s online strategy? It hardly exists. They’ve been letting people access information for free.” Tiwari’s own survey found that half of regular internet users listen to music online. Not that all of this is illegal: it’s a mix of paid-for and free downloads, but no one knows how much is which.

Saying Indians are cheap and don’t want to pay online is also a waste of time. Aren’t millions of Indians paying to access job and matrimonial websites? Aren’t they downloading billions of rupees worth of mobile phone games and ringtones? Guess which website churned $1 billion in revenues (the highest in all of South and Southeast Asia) last year? None other than the Indian Railways’s ticket portal, www.irctc.co.in. And who is buying millions of rupees worth of flights online? Clearly, there are other reasons why music, movies, TV series and software are downloaded and not bought.

“Indians believe in conserving their energy as well as their wealth,” says Dr Harish Shetty, Bombay-based psychiatrist. “Besides, Indians download all the time because of the joy of doing it in their private space.” It’s also a generational thing. Murthy cites the case of his 12-year-old son, who downloaded software manuals and, in a matter of weeks, surprised him by mastering a new package without any formal training whatsoever. “With formidably intelligent people like him all around,” the proud father says, “record labels, musicians, actors, directors, producers and software programmers will have to find new ways of making money. It won’t do to keep punching out CDs in the hope that consumers like him will keep buying.”

The music, movies and software industries know only too well that they cannot afford to be complacent. They are trying to cope by rejigging strategy. There are a variety of legal online options for people to buy from, be it CinemaNow, Vongo, ifilm, Movielink and others. There’s also a change in the mood and tone. Do we hear less strident talk of legal consequences? “Many states and companies are realising that the perceived cost benefit of piracy is eroded over time. And true, you can’t just rely on enforcement. You also need education and awareness. Cost is also an issue,” says Lizum Mishra, who heads Business Software Alliance, an international anti-software piracy lobby group.

One clear reaction is lower prices for original products. When Microsoft launched Windows 2000 in India (in 2001), it was priced at the international level—$200 a pop. Now, prices have dropped to around $22. In gaming, the popular Age of Empire now ships in a combo pack for Rs 999, three times less than two years ago. “Breaking price barriers is a simple and effective tool to encourage people to buy. Marketers are coming to terms with it,” says Prasanth Mohanachandran, most recently ED, digital services at OgilvyOne Worldwide.

.jpg?w=480&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)

But downloads are changing more than just prices. They are forcing industry to accept, bit by bit, that users will not buy content along expected lines. Take Rajjat Barjatya (of the famous Bombay film family). His four-year-old rajshree.com now hosts 1 lakh hours of free and paid-for content from his family’s production stable. Around 2 million free videos are viewed every month on the site. Rajjat’s strategy is to support free views with advertising, and charge users $9.99 to buy newly released movies ($4.99 for older releases). Still, Rajjat’s paid-for content has precious few takers—no more than 1,000 a month, he confesses, and mainly NRIs.

But at least he has demonstrated a new model, one that beats film star Sarath Kumar’s heroics. Meanwhile, across India’s cities, big and small, millions of computers are on, hard at work, late at night, downloading away.

By Pragya Sing with Chander Suta Dogra in Chandigarh, Dola Mitra in Calcutta, Arti Sharma in Mumbai, Sugata Srinivasaraju in Bangalore, Madhavi Tata in Hyderabad and Pushpa Iyengar in Chennai

Tags