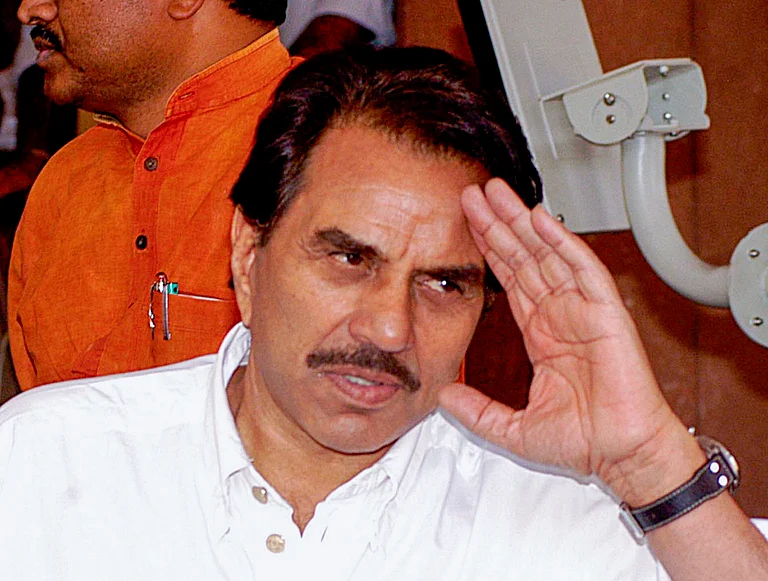

Ashok Kumar was hailed as India’s first pan-India superstar.

He took his final curtain call 24 years ago, on December 10, 2001.

He was also Hindi cinema's first anti-hero.

Ashok Kumar Death Anniversary | The Man Who Revolutionised Hindi Cinema

Kumar revolutionised not just on-screen performances with his naturalised style of acting as opposed to over-the-top dramatics, but also challenged the unwritten rules that shaped the nayak in a Hindi film and kept him distinct from the khalnayak.

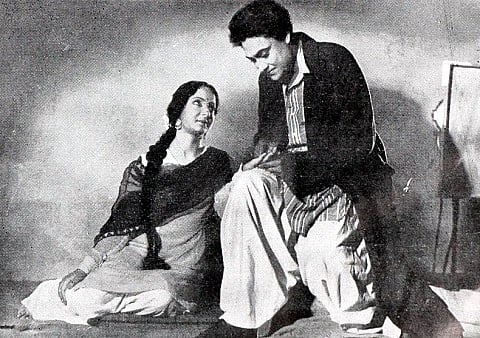

Today we remember him as a benign father or a doting grandfather, but Dadamoni, as he was fondly called, was also Hindi cinema’s first anti-hero. Before Dilip Kumar violated Nimmi in Amar (1954), Dev Anand eloped with Waheeda Rehman in Guide (1965), Amitabh Bachchan took the law into his hands and Shah Rukh Khan chose the psychotic route to stardom, Ashok Kumar’s unrepentant pick pocket in Kismet (1943) had the moral guardians up in arms. The film—which cemented the ‘lost-and-found’ theme in the minds of writers down the decades, reuniting Shekhar with his long-lost parents, and despite a succession of thefts and jail terms, rewarding him with both, a fair lady and the family fortune—led carping critics to accuse the actor of glorifying crime and influencing impressionable young minds.

I myself was young and impressionable, a cub reporter just out of college, when I met Dadamoni for an interview. As I waited for him to come down, a shepherdess in the showcase caught my eye. She reminded me of an antique figurine which had come down to my mother from her great grandmother and was a family heirloom. As I was admiring the exquisite piece of Dresden China, the man himself strolled into the room and pointing to the object of my attention with his walking stick, wondered aloud if I liked her. When I nodded silently, he told me casually that I could take the priceless art home with me.

Of course, I indignantly waved off his gift, but his careless generosity refreshed my memories of Shekhar, who commits one last robbery to finance the surgery of his crippled lady love. Earlier too, he had used his ill-gotten gains to pay off Rani’s (Mumtaz Shanti) debts. Perhaps it was this Robin Hood touch that endeared the film and its ‘crooked’ hero to the masses. Despite its flawed morality, Kismet was Hindi cinema’s first all-time blockbuster and Ashok Kumar was hailed as India’s first pan-India superstar.

However, while Kismet celebrated a golden jubilee at Mumbai’s Roxy theatre, where it premiered on January 9, 1943, and a silver jubilee on re-release—it also enjoyed a record three-year run at Kolkata’s Roxy Cinema—Sangram’s (1950) box-office reign was abruptly cut short. Another Gyan Mukherjee directorial released seven years later, the crime drama turned Kumar from a do-good con to a trigger-happy criminal. Kumar gambles, steals, abducts his girl, and indiscriminately kills anyone who comes in his way, from a rival gangster and a jealous accomplice to a posse of cops who have cornered him, till he is gunned down by his own father, a cop himself.

One of 1950’s top grossers, Sangram was triumphantly marching towards a silver jubilee, when the then Chief Minister of Maharashtra, Morarji Desai, upset with the film’s messaging, sent his top cop across to the actor’s residence to drum some sense into him and set him straight.

The police commissioner reminded Dadamoni that he was a youth icon and so needed to choose his films more wisely. He tried to argue his case, pointing out that Kumar had paid for his sins by taking the bullet at the end. The commissioner was unimpressed by his logic and the film’s run was abruptly truncated in its 16th full house week. That made him more cautious, and as his daughter, Bharti, had sighed, her father started doing “boring, inspector roles”.

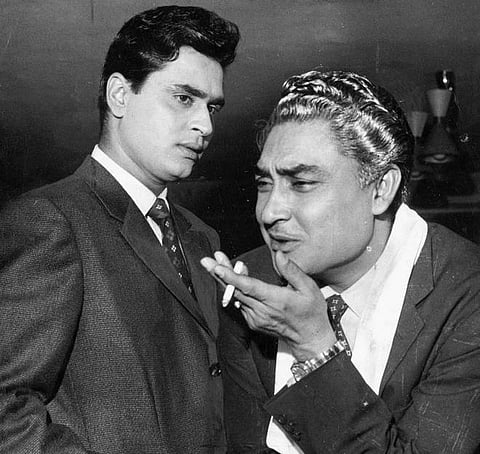

But occasionally, the man—who had bought a third-class train ticket with the Rs 35 his father had sent him for his law exams, coming to Mumbai not to become an actor but a director—would step off the beaten track. In the 1956 film, Bhai Bhai, Dadamoni’s character, incidentally called Ashok Kumar, gets entangled in an extramarital affair which takes him away from not just his city, but also his family. Eventually, his younger bhai—played by his own younger brother Kishore Kumar—unmasks his lady love as a finagler after his wealth and reunites him with his estranged wife and son. The film was a blockbuster!

The same year, he also gambled with Shatranj, a revenge drama once again directed by Mukherjee, where he traps Meena Kumari into a loveless marriage to avenge his father who is in jail because of hers for a murder he didn’t commit. Perhaps, the success of this film with a conventional ending made Dadamoni literally take the law into his own hands four years later.

In BR Chopra’s Kanoon, he plays a judge who is accused of the very crime he is trying. The 1960 courtroom drama bagged the National Film Award for ‘Best Feature Film in Hindi’ while Chopra and Nana Palshikar—the innocent man in the dock—also took home Filmfare Awards for ‘Best Director’ and ‘Best Supporting Actor’. Dadamoni once again dared to sully the image of the deified hero, and this time, he even joined hands with his filmmaker friend to do away with songs, which had long defined Hindi cinema in the eyes of the world.

While Kanoon remains a gem of a movie, the jewel in his crown was undoubtedly Jewel Thief, which made box-office history in 1967. To Dadamoni’s credit, despite his stray excursions, he had maintained a squeaky-clean image, which was why the film’s writer-director Vijay Anand insisted on him playing the ‘invisible villain’, reasoning that he would never be suspected of the heists till the last reel.

Kumar took his final curtain call 24 years ago, on December 10, 2001, 10 years short of a century run. The reason I’m celebrating his six-decade career with the bad turns he made good, instead of eulogising his on-screen virtues, is because I believe that is what he would have wanted. He shared his home with kennels full of dogs who greeted me with a wild cacophony. There must have been at least 20 of them, from huge Great Danes and fierce Alsatians to snappy Boxers and even a Sher Pei. Years later, when I was discussing him for a chapter in my book, Matinee Men: A Journey Through Bollywood (2020), his daughter, Bharti, revealed that her father, with puckish humour, had given them names like Stalin, Brutus, Chiang Kai-Shek and Hitler. Only one pet was simply called “Kukur”. When Moushumi Chatterjee protested, saying the Bengali translation of dog was hardly a name for a dog, Dadamoni retorted that he couldn’t be bothered with finding another dictator to name it after. “So, ‘Kukur’ it is,” he had shrugged nonchalantly, as everyone around him chortled.

Kumar revolutionised not just on-screen performances with his more naturalised style of acting as opposed to over-the-top dramatics, but also challenged the unwritten rules that shaped the nayak (hero) in a Hindi film and kept him distinct from the khalnayak (anti-hero or antagonist). Even after he stepped into the senior citizen bracket and moved to playing more sedate character roles, whenever a Khubsoorat (1980) opportunity presented itself, he was game to step out of line and join the chorus, “Sare niyam tod do, niyam pe chalna chhod, inquilab zindabad (Break all the rules, stop following all the rules, long live the revolution)!”

Roshmila Bhattacharya is a senior journalist and the author of four books on cinema.