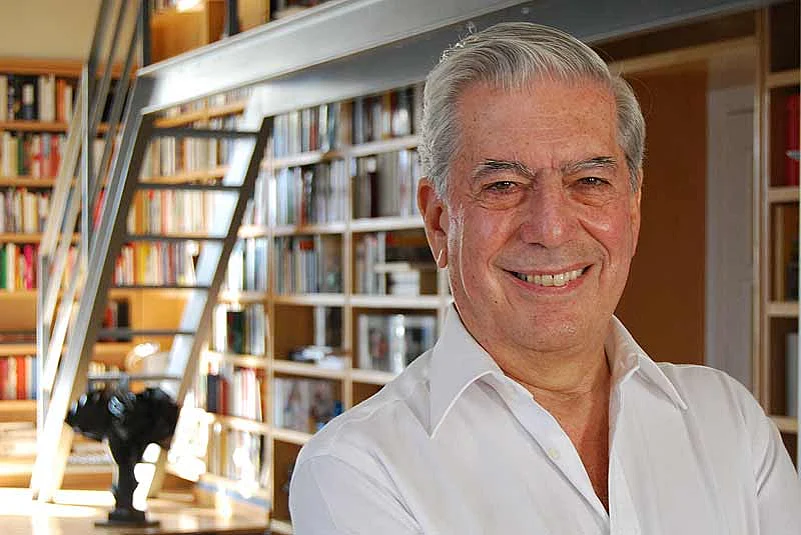

A serendipitous moment—one when you make a striking and unexpected discovery quite by accident—is the genesis of Mario Vargas Llosa’s most recent novel. A single sentence in a biography of Joseph Conrad aroused his curiosity. “Without you,” Conrad wrote to a certain Roger Casement, “I would have never written Heart of Darkness.” Vargas hadn’t heard that name before. So he began to investigate. The investigation, conducted in three continents, lasted three years. Every bit of information he harvested added to his admiration for a man who had inspired the author of one of the greatest modernist novels.

Born to a Protestant father and a Catholic mother in a suburb of Dublin in 1864, Roger Casement was brought up and educated as a pro-British Irish Anglican. As a boy, he was in thrall of his father, an officer in the Third Regiment of Light Dragoons, who would regale his children with stories of his days in Afghanistan and India. The accounts of British soldiers battling “turbaned fanatics” in the crags and boulders of the Khyber did not impress young Roger as much as the fact that his father had journeyed through landscapes alien to white men.

From an uncle, Edward Bannister, an official in a shipping company in Liverpool, he heard riveting stories about white adventurers in Africa. He was in awe of David Livingstone, a Scottish physician and evangelist, who was the first European to cross the African continent from coast to coast looking for the source of the Nile. The Livingstone saga convinced Roger that he’d spend his life courting adventure in the remotest and most exotic corners of the world.

At the age of fifteen, Roger dropped out of school and enrolled as an apprentice in Uncle Edward’s shipping company. He devoured all the literature about Africa he could find, and was convinced that “commerce with the Africans would bring them religion, morality, law, the values of a modern, educated, free and democratic Europe and liberate them from the curse of cannibalism and slave trade”. He made three trips to Africa on behalf of the shipping company and after the third one left his job to make the continent his home.

It is during his first forays in the Congo, where he was associated with Belgian King Leopold II’s project to annex the region in order to exploit its minerals—ivory, animal hides and, above all, rubber—that he befriended Conrad. The latter never ceased to marvel at Casement’s suave personality, his fluency in several languages, including local ones, and, not least, the moral vision that drove him. Their friendship would last a lifetime but end on a bitter note just months before Casement’s death.

Casement’s experiences in the Belgian king’s endeavours served him well. He was appointed British Consul and commissioned to investigate the conditions of slave labour and the conduct of the Belgian Force Publique. His Congo Report—which damned the claim that European colonialism was a benevolent force for the natives—outraged public opinion in Britain. It also fetched him a knighthood and another, equally challenging assignment: to report on the activities of the rubber barons in Amazonia. Published in 1912, this report too evoked strong reactions and eventually led to the decimation of the rubber barons. Decades later, it would be hailed as a foundational document on human rights.

Not long afterwards, Casement’s denunciation of European colonialism turned into an obsessive zeal to promote Irish nationalism. In 1914 he travelled to Germany to seek the Kaiser’s help to arm the Irish to fight the British. The treachery of his Norwegian companion led to his arrest. He was stripped of his knighthood, tried and sentenced to death despite a petition in his favour signed by some of the finest writers in England. Conrad was not one of the signatories. He refused to have anything to do with a man who had betrayed the Empire.

Before he was hanged, Roger Casement had to face another, terrible humiliation. To buttress their case against him, the British authorities leaked out portions of a diary that he had kept throughout his travels in Africa and Amazonia. They contained explicit descriptions about his multiple homosexual encounters. Whether these ‘Black Diaries’ were genuine or not is still a matter of scholarly debate. Vargas Llosa does not doubt their authenticity, but believes that many of the descriptions were no more than fantasies. For decades, Catholic Ireland, which disapproved of gay relationships, refused to grant him recognition as an Irish nationalist of the finest vintage. It is only in the 1960s that he was finally rehabilitated in the national pantheon with full state honours.

Narrated through chronological flashbacks that Roger Casement recalls in prison as he waits to mount the gallows, Vargas Llosa’s magisterial, erudite and lucid account of the life of one of the great anti-colonial fighters and defenders of human rights and indigenous cultures is a triumph of the literary imagination. It reveals with consummate finesse the deep empathy that the author feels for his subject, an empathy rooted in what they share in common. Both are quintessential outsiders but both loathe and love their country of origin. Both are globe-trotters. Both failed in their brief dalliance with politics. (Vargas Llosa contested, unsuccessfully, the presidential election in Peru in 1990.) Both speak truth to power. In Casement’s case, against European colonialism; in Vargas Llosa’s, against the crimes of authoritarian ideologies and regimes that have wrought havoc during the last century.

The novel sparkles for another reason: Vargas Llosa accepts and indeed extols the fact that heroes have their faults and vulnerabilities, something most people find hard to acknowledge. He revels in the air of uncertainty that still hangs over Casement for this, he argues, is “proof that it is impossible to know definitely another human being, a totality that always slips through the theoretical and rational nets that try to capture it”. However, the last word on the central figure in the novel belongs to W.B. Yeats: What gave that roar of mockery/ that roar in the sea’s roar/ The ghost of Roger Casement/ is beating on the door.

(Dileep Padgaonkar is Consulting Editor of The Times of India.)