On the face of it, Bassi in the district of Chittorgarh could well be just another nondescript village in Rajasthan’s hinterland, but for its vantage location on the Udaipur-Kota Road. Evident signs of its growing prosperity flank us as we cut straight through its busy centre to reach our destination, the home-cum-atelier of Satya Narayan Suthar. He belongs to the dwindling community of carpenter-artists engaged in making kaavads. This extraordinary multi-panelled and brilliantly painted mnemonic aid has its roots in Marwar but is now exclusively hand-crafted in this tiny pocket of Mewar. The cupboard-like prop has long accompanied storytellers on their travels to erstwhile durbars and noble homes; its many panels opened and closed to make stories or hagiographies progress. We park beside a large indolent bull, wholly unmoved by our presence, and walk the last few metres to the award-winning craftsman’s house.

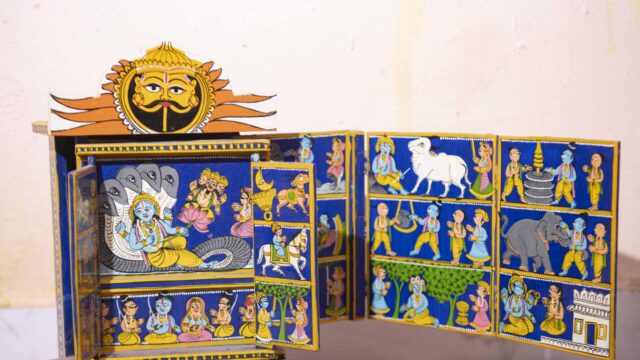

We’re told that the lesser-known art of kaavad storytelling is in fact a collaborative effort between two communities. “Traditionally, the suthars (carpenters) make and paint the wooden kaavad, and it is the kaavadiya bhats (itinerant minstrels), also called rao bhats, who recount the unfolding stories to their audience,” Satya enlightens us. We also learn that the Basatiya Suthars moved here from Nagaur some 400 years ago at the behest of the then rulers of Mewar. Interestingly though, while Marwari bhats have long practised this tradition of singing praises of royalty and narrating genealogies of their wealthy jajman (patrons), kaavad-making was unheard of before the suthars moved to Bassi. “In that sense, this is a true-blue Mewari craft,” he offers in a lighter vein, pointing out the distinguishing features of the kaavads receiving finishing flourishes. Almost all of the vibrant creations lining the shelves in his atelier sport painted narratives about gods, goddesses, saints, and folk heroes. A few of them bear the Hindi and English alphabet; still others carry numbers on the lines of school textbooks.

The word kaavad is an evident derivative of the Hindi kivaad or kapaat meaning door, and defines its form rather than function. True to folkloric tendency, its origins are also located in mythology, with several explanations for its genesis. The most invoked is the one about a woman priest with special powers from Kashi called Kundana Bai. It is said that she was granted a boon to be born anew every day, and went from being a child in the morning to an old woman by the end of the day, and was invisible to men. She is believed to have created the kaavad and gifted it to the bhats as a source of livelihood. With one condition–a part of the donations thus received must be used for the welfare of the cows of Kashi. Attesting to this legend is a tiny drawer below the front panels inscribed with images of cows. Should you look closely, you will also discover the likeness of Kundana Bai hidden away on an inner panel somewhere, as though lost in plain sight amongst the hundreds of figures showcasing tales of Vishnu and his avatars, Ram and Krishna. Another popular figure is that of Shravan Kumar. Kaavadiya Bhats believe they are descended from him.

While the size of commissioned kaavads mostly depends on audience and the number of stories they contain, a typical Marwari kaavad recounts 51 stories through 10 panels, is three and a half feet high, and has a red background. It can take over a month and half to complete, and could end up relieving the pocket of ₹35,000, approximately. The smaller ones are usually ready in two to ten days, and can cost anything from ₹800 to ₹5000. With orders for kaavads shrinking consequent to the pandemic, Satya has adapted by adding affordable wall panels, portable shrines, serving trays, and coasters to his repertoire. Regrettably, not everybody had the wherewithal to withstand the financial downturn of the last few years, and the once thriving community of 40-odd families has shrunk to a single digit. “You will find no more than two or three families making kaavads in Bassi now,” Satya trails off.

Information Box

Pro Tip: Please do not confuse this Bassi village, located about 25 kilometres from Chittor, with its namesake, a sub-divisional town on the southern outskirts of Jaipur.

Connectivity: Udaipur (134 kilometres) is the closest airport, and major rail and road head; it takes approximately two hours to reach Bassi village by cab via NH 27

Best Season: Winter

Know Your Artisans: https://industries.rajasthan.gov.in/content/industries/handmadeinrajasthandepartment/mastercrafts/NationalAwardees/list/satyanarayansuthar.html