Really, I did think I was prepared. I had looked up maps, I set aside a section of my notebook for lists, I even called ahead. Several times. But Wayanad defied assumptions. Not only is Kerala’s northern hill district still what the state used to be before it turned into a tourism case study, there is a certain uncharted quality to it, at once beguiling and unsettling. Over four days of up hill and down dale, I was frequently reminded of the importance of being earnest.

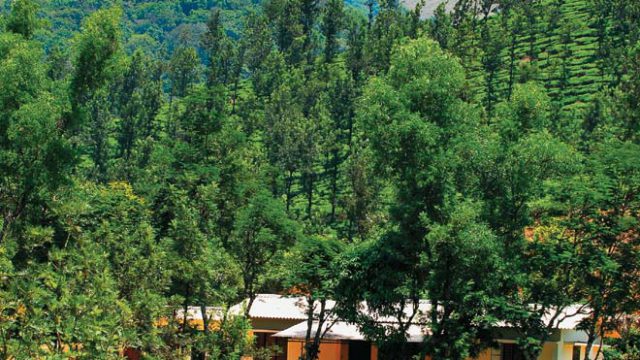

Wayanad’s rolling terrain is not only home to some of the oldest coffee, tea and cardamom plantations in India, the many valleys belong to undulating paddy fields. Claiming for its own this part of the Western Ghats, one of the world’s richest biodiversity hotspots, Wayanad offers some of the best trekking and bird-watching anywhere.

Note, Wayanad is not ‘a’ hill-station, like Munnar or Ooty, but a district. Kalpetta is the district headquarters, Mananthavadi is the junction to northern Wayanad, Sulthan Bathery is to the east. The stretch from Muthanga (en route from Bangalore, before Sulthan Bathery) to Vythiri (after Kalpetta) is promoted as a tourism belt but no such thing is discernable to a first-timer.

The scattered resorts, homestays and sightseeing spots are inevitably separated by miles of winding hill roads which makes for very slow going. Then there’s the fog, unpredictable in its arrival and departure, making for precarious travelling.

Note, too, that the District Tourism Promotion Council officers are eagerly helpful but their recommendations are not to be trusted and, indeed, they are quite notorious locally. The Wayanad Tourism Organisation, a non-profit initiative founded by property owner-managers, is trying to promote sustainable tourism and good hospitality standards, although its listings are unrated and unreliable (www.wayanad.org).

With the exception of the luxurious Vythiri Resort, there is a rugged simplicity about the Wayanad stay experience: the shampoo is likely to be a Re 1 sachet, the soap Medimix, the food simple and the glassware Yera. Luxury tax has been notified as 12.5 per cent, but many resorts still claim 15 per cent.

An important learning I must share: please avoid the Elefanta Pass, a purported tribal village experience. You will find yourself in less than two acres of elephant country with the only English-speaking person on site smelling of liquor at 9am, and sub-standard facilities being made out to be a welfare effort.

Another warning: mobile phones frequently don’t work . Since it is entirely possible to go miles with no sense of being headed in the right direction, this inability to connect for, say, appointments, arrangements or directions can get trying.

Still, this is a salubrious land. Temperatures range between five and 27 degrees year round and it rains frequently (Lakkidi records the second-highest rainfall in India). The roads are generally good and utterly scenic remote locations are merely a bone-rattling sub-5km drive away, easily reached with the help of the courteous staff of some reliable properties that offer pick-ups and escorts.

So, Wayanad absolutely must be visited. It is less than six hours on great roads from Bangalore, an hour-and-a-half from Kozhikode. A very easily connected Eden.

Besides, everywhere I went, it was the view from high points that took my breath away, not so much the exertion of getting there. The drive through the Muthanga Wildlife Sanctuary is incredible even without the elephant sightings that I was privileged with. I did not mind even the wild goose chases because they ended with genuine hospitality: a lady in a village homestay served me an ambrosial cup of black coffee, packed some nendrampazham (Kerala bananas) for me, and made me feel at home even though I couldn’t speak her language, and I am not even a coffee-drinker. And that evening, in my room, a firefly came visiting and stayed the night.