Having come to Khartoum on a mission, we wondered what to do on our day off. The city, by any standards, is not a tourist destination. You would look in vain for a guidebook on Sudan, and the situation in Darfur has tragically marked the country’s image. Yet Khartoum is an appealing city, splendidly located at the confluence of the While Nile and the Blue Nile; it is the capital of Africa’s largest country, and the heart of a history that goes back to the Bible and to classical antiquity. The prophet Isaiah has glorious words for this “land of rustling wings”:

“Go, swift messengers,

To this tall people with glistening skin,

To this nation feared far and wide,

The conquering nation of strange speech

Whose land is divided by rivers.”

Sudanese kings once ruled over Egypt, and their country claims to have more pyramids than their celebrated neighbour. One of their ancient capitals was Meroe, whose graceful name already stirred the imagination of Herodotus, the Greek historian. In his long quest for the sources of the Nile, he was told that they emerged a hundred days’ march south of the Egyptian town of Elephantine, “near the great city of Meroe”. The ruler of that city was a queen called Candace, who is also mentioned in the Bible.

With such references, it is no wonder that Meroe cast a spell on 19th century scholars. Frederic Cailliaud, a French archaeologist, desperately wanted to prove the existence of the mythical city. At that time, Khedive Ismail — who would later preside over the opening of the Suez Canal — had ambitions to conquer the riches of the Sudan on behalf of Egypt (and himself). Cailliaud tried to interest him in his search for Meroe, but the prince, who had little concern for science and history, was reticent. Cailliaud shrewdly hinted that he was actually trying to locate the gold mines of King Solomon and became the only Westerner in the Khedive’s expedition. On April 25, 1821, after much wandering, he finally walked into Meroe at dawn, as the sun rose over the long-lost pyramids. Overwhelmed with emotion, Cailliaud sat down and wept.

Of course, this was where we had to go! The road through the desert proved surprisingly good. A few hamlets, dotted with acacias, break the monotony. The first hills appear after an hour, piles of black rocks on the reddish sand; some of them look so much like pyramids that for a moment we believe we have reached our goal early. Across the desert, towards the East, a thin green line reminds us that the Nile is not far away.

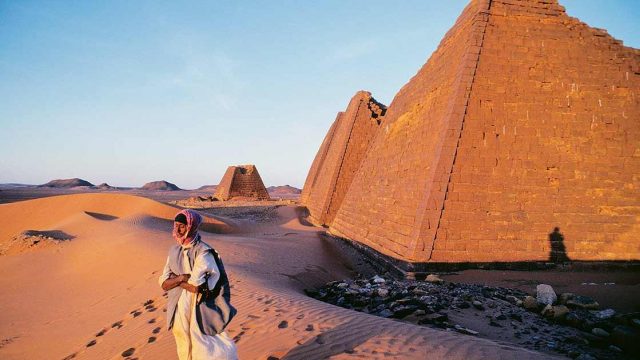

After a three-hour drive, something appears on the horizon, a strange vision oddly reminiscent of a coastal defence line, standing out in black against the red sand and the intense blue of the sky. Coming closer, we realise there are 10, 20, 30 pyramids, small and pointy, looking like a collection of building blocks. All have lost their tops. The explorers of old were not all as idealistic as Cailliaud. In 1834, the Italian fortune hunter Giuseppe Ferlini, looking for gold, dismantled the best-preserved pyramid; regrettably, he found a bronze bowl containing carefully wrapped jewels. Encouraged, he ransacked all the tombs, in vain. The magnificent ornaments of Queen Amanishaketo, who ruled 2,000 years ago, were sold to the highest bidder. They are now split between museums in Munich and Berlin.

Thirty kings, eight queens and three princes are buried here. In this surreal necropolis, we are absolutely alone, in perfect silence and crystal clear light. The architecture is drawn in crisp lines against the rich ochre of the sand, an empty gate opens up on blue sky: was there ever any human presence in this mineral world?

Walking around, we gradually find traces of the antique rulers of the forgotten kingdom. Half erased by wind and sand, a few Pharaonic scenes survive — one of a stout Candace, with short curly hair and a crown of tall feathers and ram horns; she is dressed for war. A little further, a Horus falcon testifies to the links these black Pharaohs had with Egypt. Another queen, seated on a throne, welcomes ambassadors, her husband sitting meekly behind her. In this remarkable city, the worthiest scion of the maternal line ascended the throne, regardless of sex. Hieroglyphs accompany these images. Scholars can read them, but except for a few basic words their meaning remains elusive. Meroitic, Africa’s oldest written language, is keeping its secrets.

After this dry world of sand and basalt, it is delightful to return to the Nile and picnic under the lush greenery. The great river shimmers under the sun, lined by fields of young wheat and corn. A puttering sound announces the approach of the ferryboat, a clever contraption of old sheet-iron and tubes, leisurely carrying a battered truck across the river. The boatman, all wrapped in white, greets us cheerfully and we wave back: here by the munificent Nile, only a few kilometres from Meroe, we have come back to the realm of the living.

Later in the day, we drive to Omdurman. Khartoum’s twin city is the former capital of the Mahdi, the religious leader turned warlord who defied the British Army in the 1880s. Every Friday evening, in the old cemetery of a rundown neighbourhood, Sufis dance for the glory of God, some dressed all in white, others decked out in fake leopard skins, hats with multi-coloured pompoms or delirious patchworks. A large audience of men, children, bright-eyed women in colourful veils, have come to share the blessings of the dance and of the holy sheikh whose mausoleum dominates the grounds. The atmosphere is relaxed and cheerful, and soon we are facing a barrage of friendly questions. Where are we from? How many children do we have? Are there many Muslims in our country? The man who wants to know this is astonished, then sincerely sorry for us when he hears that they are a minority in Europe. Never mind, he decides with a big smile, our presence at the zikr will do wonders for our salvation.

For this is a sacred party. The head of the zikr begins to chant: Aaal-LAH! Aaal-LAH! The chanting and dancing is hypnotic — half religious zeal, half rave party. Excitement builds, though whenever someone in the crowd becomes too keyed up, he is gently but firmly restrained.

At last, the sun goes down. The call to prayer rises in the evening air. Immediately, the dancing stops and everyone turns dutifully towards Mecca, hands raised to their ears to better concentrate on the divine message: God is great; there is no other God but God. After prayers, everyone goes home, until next week. And so do we… with their blessings in our heart.

The information

Getting there

From Delhi, Air Arabia has flights to Khartoum via Sharjah and Qatar Airways via Doha. From Mumbai, Etihad has a hopping flight to Khartoum, while Emirates has a single stopover at Dubai.

Where to stay

The Coral Khartoum (www.hmhhotelgroup.com) is a luxury option. Among other upscale hotels are the Corinthia (www.corinthia.com/khartoum), with its very eye-catching design, and the Grand Holiday Villa (www.holidayvillakhartoum.com). For information on travelling in Sudan, see www.sudan.net.

What to see & do

The Sudan National Museum in Khartoum is definitely worth a visit. In Omdurman, highlights are the tomb of the Mahdi; the very active camel market; and the Mosque of Hamad al-Niel, where dervishes gather one hour before sunset each Friday to perform their rituals. From Khartoum, you could also visit Port Sudan for a boat ride to the coral reefs on the Red Sea, and take an excursion to the off-shore island port of Suakin, which was considered to be one of Africa’s most spectacular cities in the 16th century. Meroe is located 200km north of Khartoum. There is no accommodation or food, so bring your own. It is possible to organise overnight camping trips. Your hotel can organise a car and driver for you as well as a picnic basket.