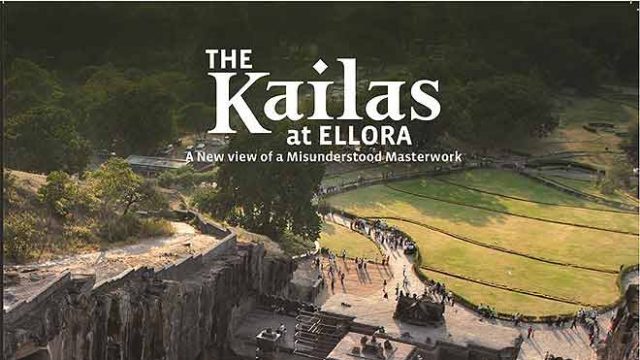

The American architect Roger Vogler has had a long relationship with India. The designer of IIT Kanpur, his great obsession is the Kailasa Temple in Ellora, which he has been visiting and studying for a few decades now. The Kailas at Ellora, a fresh look at probably the finest rock-cut monolithic temple in the world, is an intriguing and illuminating survey of the gigantic complex, its interplay of spaces and its sculptures, all from the perspective of its unknown architect, or sthapati, and of Vogel’s attempt to tease out the architectural rationale behind its construction. This is at the heart of the phrase ‘a misunderstood masterpiece’ in the book’s title. Although studied by generations of art historians, Vogel contends that no one has ever truly bothered to look at the architectural, and thereby religious, function that this cave temple might have served.

Built sometime in the middle of the 8th century CE, the Kailasa was modelled on the Virupaksha temple in Pattadakal. However, in its sheer size, the Kailasa dwarfs its predecessor. The monolithic temple or the vimana is uniquely placed in the middle of a vast courtyard with awe-inspiring overhangs of pure rock surrounding it on three sides. The complex also includes the gopuram entrance, aisles, courtyards, sculptural galleries, porches, bridges and carved freestanding pillars. In its three-dimensional visual totality, Kailasa and its environment seeks to, as Vogel rightly observes, present a unified, sacral space.

Aided by the architect and photographer Peeyush Sekhsaria’s evocative photographs, Vogler takes the reader on a tour of the cave temple, from the entrance through to the heart of the garbhagriha, where resides the lord of the world, Shiva. Vogel’s tour of this divine space is fascinating, and it serves to fill an interesting gap in the understanding of not just Kailasa, but medieval Indian architecture in general, where the focus is often on sculptures, but not the spaces they inhabit. Although the Gupta-Vakataka era is usually held to be the ‘golden age’ of South Asian architecture, the early medieval period from the 8th to the 12th centuries might have a better claim, as monumental architectural works from this period like Kailasa, the Khajuraho complex and the Somapura Mahavihara, attest.

Sadly, an understanding of the secular aspect of this complex eludes the scope of the book. Vogel doesn’t take into consideration the fact that the temple, like other constructions of this era, was built under royal decree, and Shiva’s court also served as a metaphor for the court of the powerful Rashtrakuta monarchs who patronised it. It also doesn’t address the fact that the Kailasa’s construction was part of a running dialogue of evolving architectural and religious mores in Ellora, which contains some 31 other cave complexes, Buddhist, Jaina and Shaiva. However, as a study of the Kailasa complex, this is a wonderful book.