Lookout Signs Of Abuse

Wolf In The Fairytale

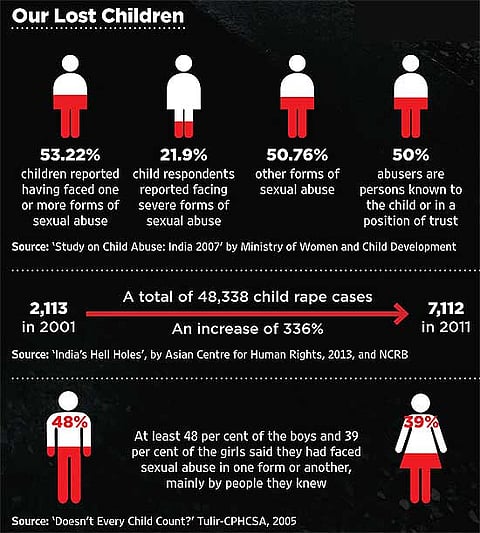

As child sex abuse cases soar, we need to ask hard questions of where our society is headed

- Evident physical signs like discomfort in urinating or defecating, urinary infections or injury to private parts

- Learning problems, an inexplicable fall in academic grades, an onset of poor memory and concentration

- Social withdrawal (such as poor or deteriorating relationships with adults and peers in general)

- Developing fears, phobias, anxieties (a fear of a specific place related to abuse, a particular adult, refusing to change into sports/swimming clothes)

- A tendency to cling on or a need for constant reassurance

- Poor self-care/personal hygiene

***

Five-year-old ‘Gudiya’ today has become a totem of rage against child sex abuse. Raped by two men, one 21 and the other 19, and then violated in a way too horrific to describe, hers is a case that should have few parallels. Yet, tragically, there are too many who have undergone similar assault and trauma. One need not even stray far from the ward in All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, where Gudiya is being treated to find more such cases.

For even now, another five-year-old is undergoing treatment here after she was raped. She was brought bleeding profusely and with severe injuries to her genitalia. In February, there was another case at the hospital of an 11-year-old from Sikar in Rajasthan, who was raped so brutally that she has had to undergo several reconstructive surgeries to repair parts of her body. So brutal was the attack that doctors reportedly had to use a portion of her intestine to repair a part that was ripped up. She is still under treatment.

But these are children who have been lucky to get support from the government and the public. Most others have no such recourse. They remain numbers, anonymous entries in our statistical record books. Here’s a fact from the National Crime Records Bureau—between 2001 and 2011, there’s been a three-fold jump in registered child rape cases, from 2,113 in 2001 to 7,112 instances 10 years later. Many more aren’t even recorded as numbers.

But who are these people behind these gruesome acts? Getting a straightforward answer isn’t easy. Contrary to the widely held assumption that child sex abusers are ‘mentally ill’, Anuja Gupta, executive director of RAHI (Recovering and Healing from Incest) Foundation in New Delhi, argues perpetrators tend to be “more like us than not us”. “These are labels we give them because we don’t like what they do,” she says. “They actually tend to be psychologically undisturbed as one needs to be very ‘together’ to abuse a child. And they’re often popular, entrenched in society.” Nimesh Desai, director of the Delhi-based Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences (IHBAS), who deals with criminal psychology, is loath to seeking any psychiatric explanation for child sex abuse. “Trying to ‘psychiatricise’ or ‘psychologise’ amounts to sanctifying their behaviour and this actually is a disservice,” he says.

But Vijay Raghavan, of the Centre for Criminology and Justice School of Social Work, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, is against creating a psycho-profile of child abusers that neatly compartmentalises them, “The offenders are hardly likely to come across as demonic after the act is committed. The seed of that mentality is present in all of us. Just that depending on the situation, it finds expression in individuals. It is painful to accept, but offenders are an extreme of the range that exists in all of us.” It may or may not be that the perpetrator was abused as a child—with our scant data, it’s difficult to generalise that those once abused themselves go on to become abusers. A more controversial association is pornography and the easy access to it via technology like mobile phones. There were reports that the two who assaulted Gudiya were drunk and watching porn clips before the crime, but a senior Delhi police officer later denied the porn link. Vidya Reddy, director of Tulir, Centre for the Prevention and Healing Child Sexual Abuse in Chennai, narrates the example of an 11-year-old who would watch porn with his uncle. “He later assaulted a four-year-old girl and tried to penetrate her with a stick. The girl bled to death.” Under-age exposure to porn poses its own issues, but can a link between porn and violent crime be sustained across the board? Especially to its most deviant form—can watching porn lead to child abuse?

Rahul Sharma, clinical psychologist at the psychiatry department, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, though believes that “access to technology like the internet is playing a role in this”. Madhya Pradesh has one of the worst figures for rape and abuse in India. Between 2001-11, 9,465 minors were raped in the state, one of the latest being an eight-year-old whose body was found near the home minister’s residence in February this year. According to police sources, 88 cases of rape of minors were reported from the state in the last 90 days (most such rapes however go unreported). S.N. Chaudhary, head of the sociology department in Barkatullah university, Bhopal, too says “small children are soft targets. The perpetrators are basically frustrated people who watch a lot of porn but cannot access sex easily”.

Schoolchildren in Jammu hold a candle-light vigil for Gudiya, Apr 20

The other view, no less disturbing, is that children are not surrogates but a specific object of desire. Pooja Taparia, executive director of Arpan in Mumbai, says what’s always present in such situations is a combination of power and sexual gratification. “If either is missing, it isn’t child sex abuse. Sadistic acts like that on Gudiya can be sexually gratifying”. RAHI’s Anuja points out that for some the “child’s body” is what gives a sexual kick. Records show that most perpetrators are heterosexual men, and the victims include both boys and girls. In a small percentage of cases, women have been found to be the aggressors.

But rape isn’t the only form of sexual abuse. It could be an adult simply touching a child’s private parts or making the child touch his or hers. Abuse can be perpetrated even without a touch, by making the child show his or her body or exhibiting one’s own to the child. It is these less violent acts that make up the larger and silent malaise of child sex abuse. A 2007 study by the women and child development ministry found that 53.22 per cent of around 12,500 children interviewed reported some or the other form of sexual abuse. “While Gudiya’s trauma is horrible, in that same period there were another 2,00,000 who were sexually abused in one form or other,” says Vidya Reddy. “Why does the media only focus on cases of rape?” she asks.

Five-year-old rape victim Gudiya being taken to AIIMS

Giving an example of the more silent forms of abuse, Vidya narrates an instance when a man in Orissa would have young boys, several of them, give him oral sex. He had told them that doing so would help them grow up to be strong like Salman Khan. The man was arrested in 2002 but he jumped bail. He was arrested again in 2009 on fresh charges but is out on bail again. “Can you believe it?” asks Vidya. Well, given the police indifference to such crimes, one can.

Dealing with child sex abuse is even more difficult in a society like ours where families often prefer to have a child keep quiet and protect their honour, especially if the offender happens to be someone from the family or close to them. Take for instance Gunjan Arora (name changed), a successful architect in Chandigarh today. She was raped for years by someone close to her family. “I was only nine and suffered it till I was 19. It really impacted me negatively. I led a life of a suppressed personality, full of fear, never daring to confront a man in an authoritative position,” she says. Gunjan finally decided she’d had enough when she realised her husband too was abusing her daughter. She fought a bitter court battle with him to save her child and is now raising her single-handedly.

Given the large number of poor children in our country, especially those in orphanages and juvenile homes, abuse even outside the family is equally rampant. Whether it is the case of Apna Ghar, a facility in the town of Rohtak in Haryana, or the home for tribal girls in Chhattisgarh’s Kanker district, rapes in shelters where our children ought to be protected are far too common. But such institutions at least do come under the vigil of data collectors, if not always of systems that ensure safety. What of the children living on our streets, begging, performing, selling trinkets? With no data, one can only imagine how vulnerable they are to free-range predators in society.

Certain primitive beliefs have also contributed to the problem, like the bunkum that STDs can be cured if one has sex with children. Also, the way society still condones child marriage—where a girl in her teens can be married off to someone twice her age—undermines every attempt to categorise the idea of child sex abuse as something deviant. Indeed, it institutionalises the abuse.

Rape accused Manoj, left, and Pradeep

The lack of sex education in schools has also fuelled the process. “It is like an outburst with no channelising. Offenders don’t even understand that the act needs to be with a consenting partner, for it’s never been taught to them. Even today, people talk about abstinence and virginity as virtues. There is no healthy dialogue about sex. What is masculinity? The projected idea is, be powerful, you can get away with anything,” says Harish Sadani, founder of Men Against Violence and Abuse in Mumbai.

In May 2012, Parliament enacted its first law specifically outlawing child sexual abuse—the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act that criminalises all forms of penetration. Earlier, different forms of abuse were covered by laws not designed to address them specifically. So if a girl suffered non-penetrative sexual abuse, incredibly, it would be classified as “assault with intent to outrage the modesty of a woman”; and if it was a boy victim, it would be dealt with the anti-homosexuality law that criminalised “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”! This often delayed prosecution as cases often fell through legal loopholes. The new act has also sought the creation of special “child courts” to try cases of abuse, something that is yet to come up in full force.

IHBAS’s Nimesh Desai sees in the spurt of child sex abuse cases a sign that those prone to such behaviour find there are few hurdles put in place by their social milieu. To limit sexual abuse, he suggests a “swift and consistent justice system”. “Other interventions include proactive and preventive policing, neighbourhood watch programmes and gender sensitisation to the best extent possible,” he adds. Senior lawyer and rights activist Kirti Singh says a “lack of certainty of justice has led to criminals and police acting with impunity. The police need clear-cut operating procedures with assurances that they will be implemented. Then we’ll see visible change”. But it’s not just the police, any effective action also requires us to acknowledge that perpetrators are from among us. We need to stand by our children, by being both more compassionate and vigilant at the same time.

By Debarshi Dasgupta in Delhi and Prachi Pinglay-Plumber in Mumbai with Chandrani Banerjee and K.S. Shaini

Tags