Telling Figures

Unreserved On The Rolls

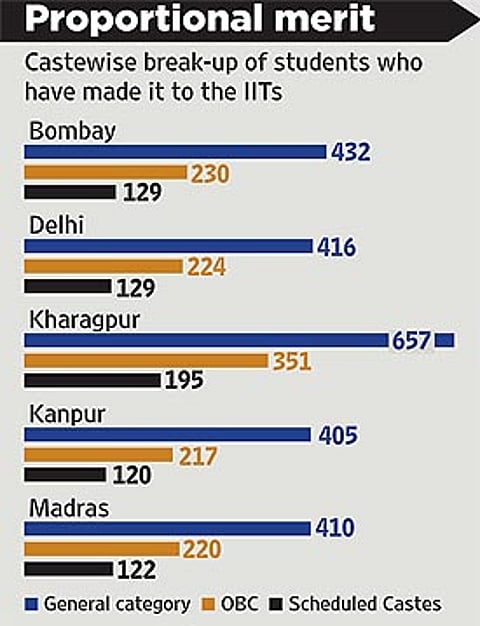

The merit argument is debunked as many OBCs make it to IITs in general category

Quota has narrowed the gap between general and obc/sc students this year

- 17 Number of IITs

- 9,867 Total number of seats

- 4,841 General category students

- 2,591 OBC students

- 1,431 SC students

- 720 ST students

- OBC candidates who joined without reservation—a little over 1000

***

For all those naysayers who felt that reservations would lower standards at the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), there is news. A little over 1,000 students from the Other Backward Castes (OBCs) have made it to the hallowed portals of the IITs without reservation. And the number of students belonging to the Scheduled Castes and OBCs almost equals the volume of general category students who are in.

Seven years ago, Delhi was under siege as students marching in the cause of a supposed equality protested against the decision of the government to reserve seats for OBCs in central and private institutes of higher education. At the centre of the debate were the IITs—prestigious institutes reputed to admit only those who cleared a tough and highly competitive entrance exam. The protesters were ready to face water cannons rather than countenance an inclusive education system, one that would allow OBC students to have a separate entrance to these hallowed corridors of excellence. But the 27 per cent reservation for OBCs in the IITs is here to stay. Though not proportionate to the OBC population, it is a cap fixed by the Supreme Court.

And the quality of the institutes has not ‘gone down’ with the influx of OBC students. While professors admit that the students per teacher ratio has gone up from 40:1 to 100:1, they are not complaining about lack of quality in their students. “The best come here—how bad can that be?” says an IIT Delhi professor. If anything, this year’s results have revealed that many OBC students did not avail of the reservation and got in through the much-vaunted criteria that the dominant forward casters often talk about—merit. The difference in the qualifying marks between the general category students and the OBC candidates is negligible.

What do the results show? For one, out of the 9,867 candidates who have qualified for admission to the 17 IITs, 4,022 are from the OBCs, SC and ST categories. The general category students make for 4,841 seats, of which more than a thousand belong to the OBCs—they chose not to avail of the reservation. The remaining are students admitted under a category for the physically disabled.

In fact, this year, of the 1.5 lakh students who qualified to sit for the JEE Advanced examination, 51,170 were from the general category and 47,085 were from the OBC category—a record high by any standards. This was also the first time that former Union HRD minister Kapil Sibal’s brainchild, a new model entrance test, kicked in, aimed at reducing stress among aspiring candidates. Though the IITs fretted and fumed at the change—accusing the minister of diluting ‘Brand IIT’, the new regime was ushered in. Students had to first clear the JEE Main examinations, conducted by the Central Board of Secondary Examinations. A little over 3 lakh students took the examination. Of this, 1.5 lakh became eligible for the JEE Advanced examination. As many as 9,867 made the grade this year. That’s how tough the competition to get into the IITs is.

A further break-up shows that 4,188 students belonging to the OBC category were called for counselling (or interviews), of which 2,591 were declared eligible for a BTech course at the IITs. Similarly, 7,436 students from the general category were called for counselling, of which 4,841 made the grade. The popular perception is that the cutoff marks for the reserved category students are heavily compromised. But here are the figures: for general category students, the cutoff is 126 out out 360 while for the OBCs, it is 113.

“The institutes were obliged to follow the SC orders that had upheld 27 per cent reservation for the OBCs,” says Anil Gupta of the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Ahmedabad. Like the IITs, the IIMs, too, had to reserve seats for OBCs. “Only the best make the grade,” Gupta says. “This is also reflected in the placements (jobs) they are offered.”

Photograph by Narendra Bisht

The number of seats at the institutes has also increased proportionately. Under the proposed system of reservations, the IITs were directed to increase the number of seats every year by 18 per cent. So 220 seats were added this year in the 17 IITs. The move was to allay the fears of general category students that reservations would eat into their seats. Incidentally, the number of IITs in the country, too, have increased in the intervening years since 2006.

The bogey of reserved seats lying vacant for want of eligible students—raised in 2006—has been laid to rest with all the seats being filled by deserving candidates. Academicians spoken to at the IITs say that all candidates pass out: once they get in, caste ceases to matter. “In a class of 100, it is impossible for me to remember the names of my students, let alone the castes to which they belong to. The students who take another year to complete their course are few and a case cannot be made out on the lines of caste,” says an IIT professor. As for jobs, once the students get into IIT, the confidence of having made it through a gruelling selection procedure perpares them for life. The grades they get in the examinations are also levelling out, say teachers.

Drawing a parallel, Gupta says, “The inclusion of OBC leaders in politics brought a rootedness to political life. My feeling is that the inclusion of students in large numbers to these premier institutes will bring in a similar rootedness.” He even has a hunch that those who leave the country immediately on passing out are by and large from the traditional elite, the upper castes. “Somehow, OBC students will stay more connected, they have a higher stake in shaping the country,” he says. That theory, you can say, awaits validation.

It was on April 5, 2006, that the former Union HRD minister Arjun Singh promised to implement 27 per cent reservation for OBCs in 20 central institutions of higher learning, including the IITs, earning for himself the sobriquet “V.P. Singh the Second”. This followed the 93rd constitutional amendment, and saw some fierce opposition from students and teachers, who felt the move would reduce the number of seats for general category students.

Doctors at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, supported by some of their teachers, struck work. The IITs stepped in to lend their might to the struggle against reservation. In the din surrounding the debate around quality, no thought was given to an entrenched elite, normally from the forward castes, that had staked its claim to these premier institutes. The debate never went on to embrace questions of inclusion: the dubious focus was on ‘quality’ and how it would be affected. That debate has now come a full circle.

By Anuradha Raman in New Delhi

Tags