The Sea And The Swamp

After the Kumbh, it’s the Ganga Sagar mela. But can the sea gods save Sagar Island itself?

“This is a centuries-old ritual...holiness has grown deep roots in this land...not even the sea gods can shake it,” says Gita Devi, 50, from Bihar, who’s been visiting the mela since her childhood. “My parents were deeply religious, and they came here to pray for a child. After I was born, they continued coming, year after year. My husband and I don’t miss a year. I cannot imagine a day when this island won’t exist.”

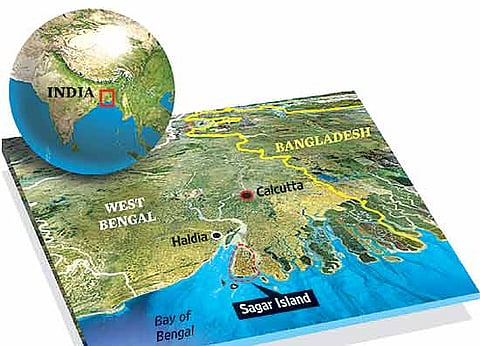

Sagar Island sits on a node, a prime target for the rising Bay of Bengal

- Where? A 300 sq km island in South 24 Parganas District, West Bengal, situated in the Hooghly delta, 80 nautical miles south of Calcutta; with a year-round population of 1,60,000 people, mainly fisherfolk and farmers. Two to four lakh people descend on the isle during the annual Ganga Sagar mela in mid-January.

- What? The island is rapidly sinking and may not exist in a couple of decades. Many of its embankments are already under water, sweet water ponds have turned salty, farmlands on the coast are submerged, an important temple has had to be moved inland three times already.

- Why? Due to climate change and a rise in sea levels, according to scientists. A nearby island, Lohachara, sank five years ago.

A neighbouring island, Lohachara, also inhabited, did sink slowly but steadily below the surface five years ago. But then Lohachara is not Sagar, which, as locals and legends tell it, is no ordinary island. Located at the point where the river Ganga flows wildly into the Bay of Bengal, it is the place where, according to inhabitants, “God came down to earth” in the form of Kapil muni. Its mela is considered the country’s second biggest Hindu pilgrimage event, after the Kumbh Mela.

A sadhu named Bachcha Shiv who has come down to Sagar Deep from a temple in Kanchrapara, north of Calcutta, reassures Gita Devi: “Kapil muni’s land will never go down...never.”

But just a few miles out, where the villages of Sagar Island stretch out along the open bay, decay and erosion tell a different tale. “The sadhus and pilgrims are living in a fool’s paradise,” scoffs Sushil Bhunyan, who lives in a village called Rashpur on Sagar Island. The 37-year-old fisherman says, a note of helplessness creeping into his voice, “Over the last couple of years, the sea has encroached on our land so fast and so furiously that we don’t know what to do, where to go.” All the sweet water ponds in the area have turned saline, he says, and farmlands have come to be submerged. “We have had to abandon our lands lining the coast and move inward. But how far can we go? The whole island will cave in one day,” he says.

Bhunyan is only too willing to take us on a tour of the devastation wreaked by the ocean. With tears in his eyes, he points towards a place in the open sea, and says, “My original hut used to be there. But the sea swept....” The high wind sweeps his voice away. A wide stretch of ground along the sea is dotted with remnants of an entire forest of trees, uprooted by the encroaching waves. The sea’s power and fury is dramatically visible, barrages built with bricks and cement have been knocked down, pounded by waves crashing incessantly against them. Almost like the boy in the legend, who put his finger in the dyke to prevent a flood, the villagers have tried to block the sea with nylon bags stuffed with sand. But to no avail—the bags too have been washed away.

Professor Sugata Hazra, director, School of Oceanographic Studies, Jadavpur University, who’s been studying the phenomenon of sinking islands in the deltas off the Bay of Bengal, confirms that Sagar Island is eroding at an alarming rate: “Sagar Island is in danger. Many of its embankments are already under water. It’s going down so fast that by 2020 to 2030, it will render hundreds and thousands of its people homeless.” He points out especially to the southern and southwestern parts of the island (which house the mela), saying they are eroding faster, not just because of exposure to the open sea but because of the crosscurrents of the confluence as the Ganges gushes into the Bay of Bengal. The culprits are the same as the world over, as Hazra avers, “climate change and a rise in sea levels”.

The Kapil muni temple has had to be moved inland three times in the last three decades (the first time was in 1977) because of the encroaching sea. Says temple priest Mahabir Das, who comes from Ayodhya to perform puja during the mela: “Scientists will have their explanations. But we have recently installed an idol of Lord Hanuman to propitiate the gods.” At least the temple authorities have a plan. The administration seems to have none, so far, for the rehabilitation of the villagers.

Back in the villages, nightly meetings are on to discuss sea levels and the surges in sea water. Most villagers cannot understand why the sea has got “even more angry”, as they put it, in the last two years. In the entire village, only one man, a schoolteacher named Ajit Kumar Das, has heard about global warming. “Bishha ushhnota? (Global warming?)” he asks rhetorically, when you ask him about the rising sea. “They held a conference in Europe. Am I right? Did they come up with a solution? Do they know what the problem is?” he sniggers. Then he says, as though it was a command. “Tell them to come to Ganga Sagar mela next time.”

Tags