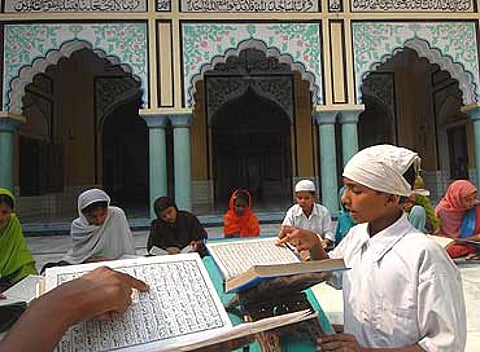

Slokas After A Noon Namaaz

Muslim children study Sanskrit and Hindu ones read Quran in these UP madrassas

This easy cohabitation of Sanskrit and Urdu in Jaunpur's madrassas could well be regarded as a legacy of the town's liberal Sufi past. "It was a centre of education in the middle ages," says Yaduvanshi, "has never witnessed a single Hindu-Muslim riot, and has always been a symbol of unity." The Salfia madrassa has, in fact, been built on land bought from a Brahmin family in 1987.

The Azamgarh-Mau madrassas too offer a counterview for an area that has of late been made infamous for its alleged association with terrorist activities. "After all, it's the land of Rahul Sankritayan, Maulana Shibli, Firaq Gorakhpuri," says Sanjay Srivastava, professor at the Poorvanchal University. "It's a literary and cultural centre and people here have been feeling humiliated for being targeted for all the wrong reasons."

At a time when stereotypes about madrassas, especially those in eastern UP, as breeding grounds for terrorists have been gaining currency and every succeeding terror attack has boxed Indian Muslims further into neat categories as either educated, patriotic liberals or misinformed, misled fundamentalists, these madrassas are a powerful rejoinder, a heartening testimony to the unspoken, uncelebrated, broad-mindedness and inclusiveness of the common, faceless Muslim. The madrassas we visit have a sizeable number of Hindu students. Salfia currently has 475 students, of whom about 225—almost 45 per cent—are Hindus. In Azizia Islamia, 35 of the 143 students are Hindus. The newly set up Madrassa Faizul Quran operates out of a small makeshift building in an obscure corner of Amari village in Azamgarh district. The maktab has 100 kids, of whom 20 are Hindus. At Arbiya, 22 of the 374 students are Hindus.

There is little to distinguish students. You know Vinky and Reena Yadav from Soni and Rehana Banu only by their names or in the way they wear their head scarves. "We don't believe in bhed bhav," says Salfia's Jalaluddin. "Tameez and tehzeeb are the same in every religion." And though the madrassas do teach hifz, or memorisation of the Quran, all have a progressive vision too. "You can't move forward with religious education alone, our students need to be taught everything: science, geography, maths, English," says Salfia principal Muhammad Saikat. It is the only school in the village which offers high school education for girls, or else they'd have to walk 10 km to the next school. The aim now is to start computers and electronics classes.

Like many others, these madrassas are yet to get government aid. There is no midday meal scheme, nor are students given free uniforms; it is all provided by the madrassa management boards. Azizia and Arbiya give students free books and charge no fee. In Salfia the fee's just Rs 5. Faizul Quran charges Rs 40 but only 10 per cent of the students pay up. The teachers themselves get no regular pay from the government but survive on the grants patrons give to the madrassas, the salary averaging from Rs 800-1,500. In contrast, teachers on the government payroll get a princely sum of Rs 3,000.

Humble and ill-equipped though they are, these madrassas are incredible examples of how Hindus and Muslims live as one than as separate entities in these forgotten hamlets. "They represent the Ganga-Jamuni sanskriti of our villages. Why would anyone want to break the sacred thread of this age-old relationship?" asks Srivastava. Why indeed?

Tags