Happy Go Roundabout

For some people, it's the default state of being. The rest of us are still learning.

But no, he rises gallantly to the challenge, switching off the TV to ponder over this life's greatest riddle. And then out pops his secret H formula—stolen, he says, from Rousseau: 1) Good bank account ("A person must be comfortably off. If not, he can have no peace of mind, and thus no happiness"); 2) Good cook ("What Rousseau really meant is the company of like-minded people and friends, to the exclusion of those on the other side. In my case, I am very allergic towards fundoos: Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, all"); 3) Good digestion ("I take it to mean good health—not athletic but not ailing. Bad health creates bad temper, outbursts of rage and inability to cope with challenges like the Mumbai blasts. One should be able to detach oneself from the events and ask oneself: What makes young men like Kasab commit these horrendous crimes? Probably he is impoverished, semi-literate, with no prospects. These youths were brainwashed by mullahs full of hatred for non-Muslims. It is these mullahs and the agencies which help them who are to blame for communalising young minds").

The thing to do when really disturbed by the news, Khushwant says, is to turn to something you love. "I turn to listening to classical music, preferably Western, and reading poetry, both Urdu and English. I am then transported to another world, free of hate and full of wine, women and song."

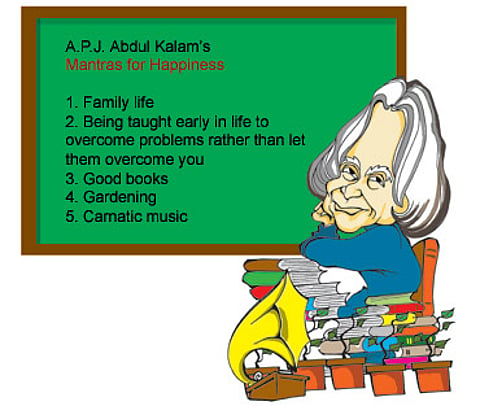

I brace for some grating self-help advice, but instead, he leans both elbows on the glass table and, smiling benignly, spells out his list: 1) Family life, 2) Being taught early in life to overcome problems rather than let them overcome you, 3) Good books, 4) Gardening, 5) Carnatic music.

Family? What family? Turns out that bachelor Kalam has been hiding 26 grandchildren, the eldest of whom has just had his own first granddaughter, Hanija, three months ago. Kalam's face lights up at the mere mention of his great-great-"golden"-granddaughter. Hanija and the grandchildren may not technically be his but his four siblings', but for Kalam, there's no difference; his is a joint family, he says. One of the grandsons, in fact, is living with him while he studies for the administrative services exams. Thanks to cellphones, Kalam says, he's in almost daily touch with his large family spread across the country, from Rameshwaram to Delhi.

The first hour of the day—at least whenever he isn't travelling—Kalam spends with his new gardener, Kanchan. And like Kanchan, he "enjoys whenever a flower blossoms". It's hard to be downcast, he feels, while there are flowers, books and music. Reading of all kinds is an abiding joy—he watches no TV, relying on the radio for the news—but there are a few favourites that he turns to for solace. One of them is a battered book he found in a second-hand shop in Chennai's Moore Market over 50 years ago: Light from Many Lamps by Junior Watson. "This is a book that levels me when I'm too happy, and comforts me when I'm in trouble," Kalam says. But when I search for it on the web, all I can discover, puzzlingly, is that it's listed among the 50 worst books of the century. The other favourites: Five Minds for the Future by the Harvard professor of education, Howard Gardner, and Tirukkural or Lights of the Righteous Life, a collection of 1,333 couplets on everything, from virtue, wealth and the State to love, hope, family life and contentment, by the Tamil poet-saint, Tiruvalluvar.

The real key to what keeps Kalam going, not quite merrily, but with a boundless enthusiasm that is almost infectious, I only discover as he escorts me out of his new residence—to call this maze of impersonal waiting rooms and receiving rooms, with the blankness of a dentist's office, a home would be an exaggeration. "You can't go searching for happiness," he says quietly. "You only get it by giving it." Sounds like self-help? Perhaps, but the words are redeemed by his patent sincerity.

Kalam's homegrown rules on how to stay upbeat coincide remarkably with a professional's. For instance, psychiatrist Dr Avdesh Sharma's advice to the increasing number of patients seeking medical help for attacks of panic and anxiety is invariably: 1) Spend time with your family, 2) Maintain good health, including regular exercise, 3) Take up a job, paid or unpaid. Concern for others is a good cure for the blues. 4) Start meditation, even a few minutes of it is good enough to remember that this too shall pass.

I ask Dr Sharma the only question worth asking: Is he happy? He laughs, unusual for a practising counsellor who spends his working day listening to patients with serious mental problems. "I am fairly content and happy. Of course, I do have my ups and downs but I am more aware of them now and work on it." What helps him get through a bad day, he says, is being with his children, going for a walk, and reading a good book, mostly self-help. And meditation.

It wasn't always so. Ten years ago, he says, he felt burnt out. "Dealing with major problems like addictions and so on wears you out." He decided to turn to what he describes as fellow "mental health professionals"—spiritual leaders like Ravi Shankar and the Brahma Kumaris. "It was a humbling experience," he says, and also very challenging.

In the West, positive psychology or the science of happiness is over a decade old, started by Martin Seligman in 1995, and quickly gathering steam until departments in nearly all universities abroad now research the elusive secrets of mental well-being. But in India, Dr Sharma points out, professional psychologists are still stuck in the conventional western methods of focusing on unhappy people, rather than studying what makes one happy. That's a territory, Dr Sharma points out, that has been claimed by the "well-being sector" of spiritualists, temple priests and even astrologers—at least when they're not scaring you into spending money on mumbo-jumbo.

My own brush with spiritualists is strictly limited. A couple of years ago, curiosity drove me into Anandmurti's ashram in Sonepat, on Delhi's outskirts. It wasn't the kind of ashram I imagined—air-conditioned meditation rooms with glass doors overlooking flower gardens, comfortable rooms with attached bathrooms, dining halls so clean you could eat off the floor, and a coffee bar for youngsters who wanted a change from the ashram's sattvic diet. And to top it all, a spiritual leader who combined good looks with a powerful singer's voice. I watched her flock of mostly youthful disciples—engineers, chartered accountants, management graduates, bankers, students—slip into an ecstatic trance as she sang Rumi's poems in Hindi, and depart from the gathering happier than before. To each his own.

In my neighbourhood park, I watch a group of old men solemnly form a circle, scoop their hands down and fling them up skywards, and do what they possibly haven't done since childhood: laugh hysterically. The sound frightens my dog, Cookie, but it seems to work for them, even if it's merely a victory over their fear of looking ridiculous. "I feel happier since I joined the laughter club six months ago," insists Satish Ruhal, a TV cameraman who religiously gathers here with some 25 others to laugh his way to good health every morning, come rain or shine.

More recently, I went to hear Thich Nhat Hanh, the Zen Buddhist monk originally from Vietnam. I wasn't the only one, it seems, in search of that elusive thing, call it what you will—peace of mind, destressing techniques, anti-depressant or even, why not, happiness. Several hundred people, including Priyanka Vadra and her husband, and Rahul Gandhi and several young parliamentarians turned up at Teen Murti for the five-day retreat, where they did nothing more pressing than just sit around in silence, learning the lost art of how to live fully in the present moment.

But what works just as well for me is living with Cookie. Each morning, as the hour for our morning walk approaches, her excitement grows until she can no longer contain herself, barking wildly as I get my shoes on, and shaking with such exhilaration that I can't fix the leash on her collar. How can you stay angry with a world that holds a creature so eager to greet the new day?

Tags