Eden's Secret

It's a nook of paradise where no outsider has set foot in 60 years. <i >Outlook</i> goes into Gurez in Kashmir for a first-hand account.

***

As alluring as Gurez's natural beauty is its unique culture—its 30,000 inhabitants are known as the Dard-Shin, who are ethnically and culturally distinct from Kashmiris or Ladakhis and closer to the people of Gilgit and other regions of the Karakoram across the LoC. Popular anthropology often likes to ascribe an 'early Aryan' origin to them, though older references present a messier picture of a loose grouping of hill tribes. Their mother tongue is Shina, a 'Dardic' sub-group of the Karakoram tongues, loosely related to Kashmiri, with a trace of early Sanskrit, a twang of Tibetan come through contact, and even words that are said to be akin to Hebrew.

The Dard-Shin of Gurez have had no involvement in the militancy. They are mostly pastoralists, with cattle as their main source of livelihood. Once, they were busy traders as well. Gurez was a stop on the old Silk Route, which ran from Srinagar and Bandipora through Gurez, then on to Dras, Kargil, Leh, and Tibet. The medicinal herbs that grow in the pastures here were a much sought after item, and credited for the longevity and hardiness of the locals. One of them was a legendary pehalwan, who during the '71 war with Pakistan single-handedly carried artillery guns up steep hillsides to their positions. Local lore has it that evidence of his Herculean feats can still be seen in his footprints, imprinted on rocky slopes in the valley.

Of course, the uglier relic of history is the thick concertina fencing of the LoC which snakes through the valley. It winds by roadsides, along the banks of the Kishanganga, through grazing areas, sometimes cutting right across a village, dividing it into two. "This razor-wire fence has cut deep wounds into our lives, It has divided neighbours, destroyed our way of life and our livelihood," laments villager Abdul Gani Lone. Every winter, heavy snowfall and avalanches bring down the fence, sweeping the wire into the grazing areas, the small patches of cultivable land and even the river. It is never removed. Come summer and the army simply erects new fences. Says Lone: "The debris of old, broken fencing makes it dangerous even for the animals to cross the river, apart from preventing us from fishing. My mule, which I had bought for Rs 28,000, just died after it got caught in the fence. "

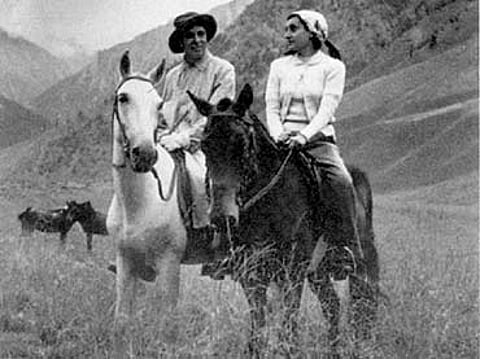

Now Gurez's villagers are banking on tourism to provide them a new source of income, if only for a short period from June to September. For much of the rest of the year, Gurez is snowbound and inaccessible. "Finally, we'll get to see some money in our hands and some development," exults Ghulam Mohammad Lone of Malangam, a village just a few hundred metres from the LoC. The older generation remembers a time, in the colonial period, when Gurez was a trekkers' paradise. Nehru and Indira Gandhi, accompanied by Sheikh Abdullah, were among those who loved trekking here in the '40s, fishing for trout at Naranag, one of the tranquil lakes in the mountains above the valley.

The state tourism department is now promoting several one and two-day treks. Two such treks—from Tileil to Jawdara via Gangbal, and from Burnai-Jawdara-Kangan via Naranag—traverse breath-taking Himalayan mountainscapes, and lakes set amidst flat pastures that offer excellent camping sites. Another route, from Markoot-Kesar and Dawar to Patalwan, crosses dense pine forests and Gadsar Lake, a big draw for anglers. Gurez also has a variety of rare wildlife, such as snow leopard, musk deer and ibex, with their environment so far relatively protected compared to rest of the state. Rafting on the Kishanganga, a tributary of the Jhelum, is also being promoted. For nature lovers, June and July are the best months to visit, when the entire W-shaped valley is a blazing carpet of alpine flowers.

But clearly, a lot more needs to be done before Gurez can fulfil its potential as a tourist paradise. One problem is the inner line permits which all visitors, Indians and foreigners alike, require from both the district and army authorities. "We have requested the government to let the tourism directorate be the nodal authority to process permissions," director of tourism department (Kashmir) Farooq Ahmad Shah told Outlook. But will the army agree? Gurez has been one of the shortest infiltration routes from PoK into Kashmir and, not surprisingly, the army is worried at the prospect of tourists wandering freely in the area. Defence sources in Srinagar say the army must also be involved in processing permits, and the areas where tourists can go will have to be clearly demarcated. But for now, Gurez locals are dreaming of seeing their serene, forgotten valley transformed into a buzzing resort.

Tags