Drink To The Dregs

Nawabiyat is a pale memory...and wasika a poor cousin of the privy purse. Yet that one monthly tryst links them to a lost spring.

There is this same pinch-me-and-I'll-wake-up quality to other encounters with descendants of kings, noblemen, officials and servants who were dear enough to Avadh's rulers, or powerful enough, to receive legacies until perpetuity. There are about 1,200 such wasikadars, living mostly in Lucknow, most of them Shia Muslims, as the rulers were, and receiving small sums, between Re 1 and Rs 570, many from multiple sources, because of a maze of intra-family marriages. They are the surviving remnants of a court that unravelled in 1856 when the British deposed Wajid Ali Shah and dumped him in Calcutta. And they care enough about their connection to a distant royal past to show up every month, or more usually, every few months, at the Wasika Office, a minor tributary of the UP government.

On a good day, you see a stream of well-worn bush-shirts, sherwanis, kurtas, burqas and naqabs lining up before clerks who receive them with the familiarity, and the ennui, of old acquaintanceship. They belong, it turns out, after many paan-scented conversations, to zardozi and chikan workers, agarbatti sellers, a former munshi in a fruit mandi, a small farmer near Lucknow, a maker of Shia symbols, a clerk in the secretariat, a one-time canteen contractor, a medical photographer in a hospital. Indigent widows who live on dilapidated wakf properties explain the value of their wasika in fragments of sentences—"Khandaan ki pehchan...purkhon ki nishaani...(Mark of our lineage, and of our ancestry).

The conversation swirling around the room is a jumble of odd sums like Rs 5.84 paise and Rs 11.46 paise and the intriguing names of various financial instruments that several of Avadh's rulers negotiated with the British (see box) to provide for their descendants—Amanat, Zamanat, First Oudh Loan, Third Oudh Loan, Salar Jung's Mahal.

Genealogy rules in this little world, almost hermetically sealed off from a Lucknow dominated by giant hoardings of a smirking Mayawati, and stretches of real estate called Sahara. Chatting with 90-year-old Sadiq Ali Mirza means travelling seven generations down from Saadat Ali Khan, one of Avadh's more competent rulers, the name of each ancestor carefully enunciated in a soft, almost trembling voice. Until the time of his grandfather, the wasika paid the bills, explains Mirza, disappearing briefly into a nostalgic world of Re 1 for a seer of wheat, and 18 annas for a seer of desi ghee. As the legacy got divided and subdivided down the generations, and lost its monetary value, Mirza's father took the first, humbling steps into paid employment. His chaste Urdu and knowledge of religious texts had no currency in the marketplace, so he became a mechanical draftsman in a paper mill. Mirza went in search of petty babudom, becoming a sub-accountant in the Central Bank of India, his sons have embraced modest entrepreneurship—a small printing business, and a zardozi workshop.

Mirza's wasika is his only proof of pedigree—tucked away among the dhobi bundles in the Wasika Office's record room is a shajra or genealogical tree, with his name on its last branch. After him, his children's names, and their children's names, will be added to it. Until the wasika itself dwindles to Re 1, and gets commuted—an official policy that, not surprisingly, gets a thumbs-down from most wasika-holders.

With variations, my conversation with Mirza repeats itself as we trawl neighbourhoods called Husainabad, Muftiganj, Kashmiri Mohalla, Pata Nala and Wazirganj, where 'nawab' is equally a term of respect and sardonic irony, passing every now and then, a home with two curved fish (the emblem of Avadh's rulers) embossed on its front. In the drawing-room of Zaigham Uddin Haider, a retired principal of the Shia Inter-college, and a great-grandson of Wajid Ali Shah, we finger copper coins struck by Avadh's rulers and admire his son's wedding card, embellished with royal titles. The son, visiting from Dubai, where he works for Baskin Robbins, explains earnestly that even in that world of Arabs and migrants, belonging to a family of wasika-holders is not irrelevant, if only to depress the pretensions of Hyderabadis who also work in those parts.

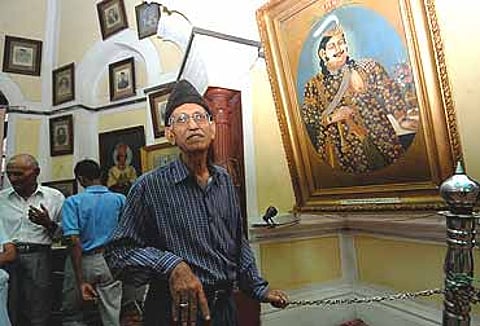

Later, we revisit the past again with Yusuf Akhtar, another great-grandson of Wajid Ali Shah, living in dilapidated quarters off one of Lucknow's smaller Imambaras (congregational halls for Shia mourning), as he identifies the line-up of Lucknow grandees in Persian caps in a picture of his grand circumcision ceremony. Further down the wasika trail, we meet Hussain Ali Khan, an illiterate rickshaw-wallah, who lives mostly off the charity of relatives, his family's avowals of nobility so out of sync with the present that nobody can even recall its faint contours.

Haider Mehdi, a Lucknow academic who undertook the first sociological study of wasikadars, recounts that more than 70 per cent of the 300 wasikadars he interviewed for his PhD thesis earned less than Rs 5,000 per month, and only a tiny minority could be said to be leading "normal middle-class lives". Moved by their situation, he quotes Ghalib: "Banakar faqiron ka ham bhes Ghalib/ Tamasha-e-ahle karam dekhe hain (Disguised as a faqir, I watch the games of the high and mighty)." However, the picture that emerges from his survey is of a set of people that have participated in their own decline—largely poorly educated (over half of those he interviewed were educated up to primary school, and only 15 per cent were graduates), socially conservative, and politically apathetic, showing up for Moharram rituals, but not using their rights of participation in Shia trusts.

Habib Ali, a descendant of Avadh's wasikadars and taluqdars, and an economics professor, offers a history lesson. He stresses the impact of the zamindari abolition act and other state policies, but combines it with a sympathetic yet incisive critique of a wasikadar class that lived off past legacies without seeing the shape of the future, and failed to invest in modern education. And sums it all up with the elegiac elegance of the true Avadhi: "Rafta rafta waqt badalta gaya magar ham na badle, haalaat badalte gaye magar ham na badle, hawaon ke rukh badal gaye, ilm ke paimane badal gaye, phir bhi ham na badle (Time changed but we didn't, conditions changed but we didn't. The winds changed direction, standards of knowledge changed, but even then we didn't change.)" They are changing now, says Ali. Hardworking artisans have learnt, painfully, the value of education and are sending their children to school. But it will take more than a generation, he says, to catch up with the middle class. And even longer, perhaps, to soar towards modern nawabdom.

Tags