But Then Kashmir Is Not Yet Free

Manacled and left to rot for 35 years, freedom's lofty rhetoric is just words for Kashmir Singh

The two were separated in 1974 when Kashmir, then working as a spy for the military intelligence, was arrested from a bus near Rawalpindi. He had earlier served in the army, which he left to join the police when his wife fell ill with tuberculosis. Suspended for a minor misdemeanour, the adventurer in Kashmir drew him to spying, a lucrative vocation in those post-1971 war days. "I was paid a princely sum of Rs 480 a month, besides a lump sum Rs 5,000 when I joined the MI." He never knew it, but spies, once captured, cease to exist for the military. His wife, two sons and a two-month-old daughter were left uncared for. Paramjeet sold her jewellery, and did odd jobs to make ends meet. The burly Kashmir was shunted from one jail to another. His trial lasted two years and 11 months; then he was sentenced to death for spying. The execution was stayed in 1977 and again in 1978, after which his file went into legal limbo. Kashmir was forgotten till 2007, when Ansar Burney, then Pakistan's minister for human rights, chanced upon him in a Lahore prison. Through his good offices, Kashmir, known to inmates as Mohammed Ibrahim (he converted to Islam), received a presidential pardon.

Kashmir's bewildered visage at his homecoming, showing a man more overwhelmed by the quirk of fate than joyful, was plastered across newspapers. His easy smile has since been replaced by a perpetual frown, but his alert eyes, alive with a thousand experiences, dart restlessly about. They speak of a never-say-die survivor. "In the initial years I used to pick up fights. Gradually, over the years, in chains and on death row, I took to Islam. I have read the Quran 1,200 times. It gave me solace. I used to heal people in prison by reading verses from it. They would call me 'ustaad'. I believe in it and am trying to procure a copy from a mosque nearby," says Kashmir. All through the long, dark years, Ibrahim never lost hope. "I used to miss my family intensely. But even through the darkest despair my spirit remained alive. That saw me through." The same spirit which led him once to physically punish the village SHO for beating his own wife, or to defy his parents to marry Paramjeet. "He used to be Nangal Chauran's homebred daredevil, always in trouble," recalls his childhood friend Tarsem Singh.

With half his life spent behind bars in a hostile country, taking to a new religion, did he ever feel well disposed towards his captors? "The betrayal by fellow spies, which led to my capture, left me bitter. Though the jail staff were nice to me, I made just one friend. But I did build a foster family of sorts. I have two sisters, two sons and a mother in Pakistan, all of whom are relatives of fellow prisoners who were hanged for different offences," Kashmir tells us. His foster son Sher Khan called him up a few days ago to protest his taking to Sikh ways again. "He was surprised to find my Muslim persona diluted. Told me that they never suspected I was not a Muslim. That's not true though. If there is anything I have learnt in jail, it is that no religion is good or bad," he says.

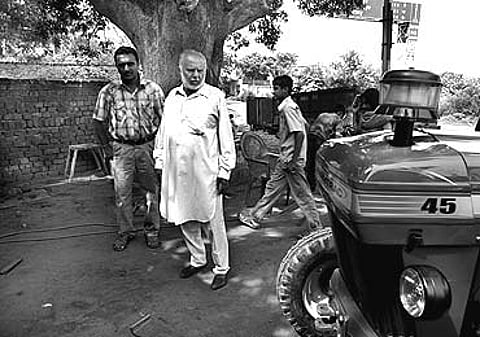

Kashmir is trying desperately to procure passports for himself and his wife to go to Italy to meet their daughter and son. That quest has run into a roadblock as the establishment dithers over a decision to allow him to travel abroad. His former employers, the MI, too have not bothered to meet him since he returned. "Though the Punjab CM gave me Rs 10 lakh and a plot of land, the Centre's silence is painful." But Kashmir isn't one to brood and sulk over things. Even this hurt, the years of neglect of his family, doesn't weigh him down. He has a small fan following in his village: a few hangers-on born much after he left. The affectionate regard of the residents of Nangal Chauran, learning the finer points of driving a tractor or just penning a little ditty to Paramjeet, who sits close by, fanning him indulgently with a smile, are all the balm he needs.

Tags