Backwoods Babus

Children of rickshaw-pullers, farmers, clerks are cracking the IAS. Will they lead to a better, kinder bureaucracy?

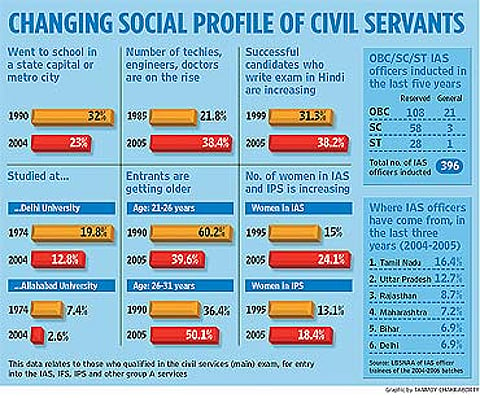

- Less than 2 in 10 entrants were from a metro or a state capital in '04

- More than 5 were born in a tehsil or district town in '04

- One out of four are kids of fathers who have not studied beyond matriculation

- 4 in 10 were engineers, techies or medics

- New recruits are older. About 50% in '05 were over 25.

- 4 in 10 now sit for the exam in Hindi, but English-types still have the upper hand

- 12 of top 50 rank-holders in the latest (2006) civil services exam are OBCs

- 32.5 % of IAS officers inducted in the last five years are OBCs

- Despite reservation, only a tiny fraction of civil servants are first-generation learners

- More women are making it to the IAS

- Tamilians and UP-ites dominate the last three years' IAS intake

***

Wajahat Habibullah IAS, 1968. Educated at Doon School, St Stephen’s. Retired as Secretary Ministry of Textiles, currently Central Information Commissioner.

Mani Shankar Aiyar IFS, 1963. Educated at Doon School, St Stephen’s, Cambridge. Was Consul-General in Karachi. Joined politics. Now Panchayati Raj minister.

Natwar Singh IFS, 1953. Educated at St Stephen’s, Cambridge. Served as Ambassador to Pakistan. Resigned to join politics, became Minister of External Affairs.

Virendra Dayal IAS, 1958. Went to St Stephen’s, Oxford. Was Under secretary General of UN. Now, Member, National Human Rights Commission.

***

Son of a munsif (court clerk) in Sasaram district in Bihar, he did his BA by correspondence. Though he lived one km from the district collectorate, he never got within conversing distance of a district collector, but like all bright students in Bihar, he was encouraged from childhood to join the IAS. He got in on his seventh attempt.

"Bihar has not seen the winds of change that swept through the country from the ’90s, so we have an older mindset. For us power and prestige still means sarkari naukri, rather than the fat salaries of MNCs."

Walking into Outlook's Delhi office a few weeks after he was selected—with a distinct air, if not a swagger—Sanjay relives those heady moments when he was swiftly transformed from a small-town boy with uncertain prospects into a member of the mai-baap sarkar that personifies power in his home state. The euphoria of family and friends, the sudden warmth of neighbours who had written him off after he flunked, gushing calls from mere acquaintances and even strangers. The tears of his father, a clerk at the district court who had spent a lifetime in awe of three conjoined letters, I, A and S. And the attentions of bridegroom-seeking civil servants and local politicians belonging to his Rajput caste. They were the only ones disappointed. At 29, the new probationer was already married.

Sanjay is the new face of the civil services. Agastya Sen, the metro-born protagonist of Upamanyu Chatterjee's 1988 novel, English, August, with 'St Stephen's College' written all over him, who finds himself in a district town—a "dot in the hinterland"—after joining the IAS, is even more of a rarity than he already was in the '80s and the '90s. The most recent data on the social profiles of the 400-odd who annually clear the civil services exam conducted by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) to join the IAS, the Indian Foreign Service, the Indian Police Service and other services, shows that the numbers of those born and schooled in "dots in the hinterland" is rising steadily. The city-born and city-bred, apparently chasing IIMs, MNCs, foreign universities and a plethora of new-economy options, are painting themselves out of the picture. "The easy availability of good jobs not requiring such hard work and preparation to get into, have turned people from relatively affluent backgrounds away from the IAS," says ex-IAS officer and National Advisory Council member N.C. Saxena.

His father used to pull rickshaws, now he rents them out. He went to a government school and a modest college in Varanasi, His family sold land to finance coaching classes in Delhi. He got a dozen marriage proposals after the results, one from the family of a local liquor king, offering Rs 4 crore as dowry, but he turned them down.

"I decided to try for the IAS because this is one government job where you don’t need money or approach to get in, and I had neither.... Earlier, the police used to harass my father, now they do ‘sir sir’."

According to data, in 2004, less than two out of 10 entrants into the civil services were born in metros and state capitals. Three out of 10 were born in villages—and as many as half were born and schooled in district and tehsil towns. Compare that with the '70s, when two out of three civil service recruits were from cities, and the '80s, when one out of four still was. "It is a sign of a healthy democracy, of expanding opportunities," says Rudhra Gangadharan, director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA), where new recruits are trained. "People who had no access to the civil services are coming in." But for a mix of reasons.

"I came in accidentally. My family has land, but my brother, who had failed seventh class, decided to work on it. The land was not yielding much—so I decided to look at a government job, and found getting into civil services was possible. Options like joining IIMs or MNCs or starting businesses are not available to lower-middle-class families, we don't know about them," admits Pandurang Pole, a young IAS officer from Maharashtra in the J&K cadre. Says V. Anbukkumar, another young IAS officer, whose father was a police constable, "In a village, authority means the collector. He is the face of the government. In the absence of many educated people around, the DM became my default role model." Of course, the bigger the role of government in a state, the greater the quest for government jobs. "Bihar has not seen the winds of change that swept through the rest of the country from the '90s, so we have an older mindset. We equate sarkari naukri with power and prestige," says Sanjay.

Son of a retired police constable from the backward Vanniyar community, Anbukkumar (in the dark suit) went to school in village Chinnapalli Kuppam, Tamil Nadu. His siblings still work on the family’s 4.5 acres of land. He travelled to Chennai for his BA and MA, and got into the IAS on his 7th attempt, but didn’t take any private coaching. It was his father’s dream that he become a police officer, but Anbukkumar wanted to join the IAS.

"In our country, there are three people who are the most powerful—PM, CM and DM. I wanted to be a DM."

About 30 per cent of civil service entrants are, like him and Anbukkumar, the children of government and semi-government employees. But, says ex-IAS officer Wajahat Habibullah, who interacted with three recent batches of young civil servants as LBSNAA's director from 2000 to 2003, that is less and less likely to mean children of senior civil servants. "The children of IAS officers do not want their fathers' jobs," he says, a little ruefully. "But there is an influx of the children of those who worked in the lower ranks of government service—like head constables, private secretaries and clerks—for whom the IAS was the ultimate." Also, curiously, a continuing influx of technical people, like engineers and doctors. "These are often people who've grown up in a rural area or a district, gone to a medical or engineering college, but after that, don't want to go abroad, where the best-paid options are. They want to stay in India, look after their parents," says Habibullah. Adds an IAS officer from an engineering background, "A civil engineer who joins the government engineering services will never become more than chief engineer. An IAS officer goes much further, so they would much rather lose their specialisation and join the IAS."

He comes from Chinnagollapalem village in Krishna district, Andhra Pradesh, where his father and two brothers are farmers. Muthyalaraju studied in the village school and did his B Tech from Regional Engineering College, Warangal, and his Masters in Bangalore. His family borrowed money for coaching classes in Delhi. He got into the IPS in 2005, but tried again for IAS and topped in 2006.

"The death of my 12-year-old sister due to poor medical facilities in the village spurred me in the direction of the civil services."

Their story is often one of impressive mobility—the story of a changing India, as much as a changing civil service. Studious and focused 'Bunties' and 'Bablis' from village, tehsil and district schools sally forth in search of higher degrees, reaching Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and Delhi University, sundry engineering and medical colleges and established state universities. Aboobacker Siddique, a farmer's son from Malappuram district in Kerala, makes it to JNU, where a section of the library, taken over by civil service swotters, has been christened Dholpur House, after UPSC's headquarters. Sujit Singh, son of a havaldar in Bihar, makes it first to Delhi's Hindu College, and then to the civil services. Anbukkumar, a constable's son from Tamil Nadu, goes to the elite Madras Christian College in Chennai for his MA.

However, an increasing number do not travel that far, picking up a degree or two from a modest institution nearer home, and a distance learning course. Many less known institutions are chipping away at the dominance of the civil services by established universities. The intake from Delhi University, even if still high, has declined considerably since the '70s. Likewise from Allahabad University, whose silver-haired alumni adorn the upper reaches of the bureaucracy. Calcutta University has fallen off the map. Showing up on the map are little-known colleges and universities in places like Tiruchirapalli, Warangal, Izatnagar, Kolhapur, Bareilly, Rohtak, Meerut, Bhagalpur, Amravati, Belgaum, Nagarjunanagar, Gorakhpur, Gulbarga, Bikaner, Sagar.... And three per cent of the intake is now from distance learning courses.

Married at an early age, Sudha (looking up) had to give up her studies. When the marriage broke up after four years, she finished her BA from Coimbatore, and prepared for the civil services, which she cleared at the first attempt, after joining a coaching institute in Delhi. The daughter of a farmer, she grew up in the tehsil town of Tiruchengode, Tamil Nadu.

"My humble background makes me better able to understand and relate to people’s problems. When I see a farmer with grievances standing in front of me, I see my father."

Greater access to the system helps. Until the late '60s, the civil services exam was the preserve of the English-educated. It could not be taken in another language. Thereafter, candidates were permitted to take some papers, and then all except one basic qualifying English paper, in an Eighth Schedule language. Weightage for the personality interview, in which candidates from elite backgrounds are perceived to have an advantage, was reduced. (It is now just 13 per cent of the total marks). Changes like these helped Malegaon boy Mohammad Qaiser and Varanasi lad Govind Jaiswal make it to the top this year.

Twenty-nine-year-old Qaiser, who took the exam in Urdu, was disappointed by his poor interview result. It did not stop him, however, from standing 32nd in a gruelling three-part exam taken by one-and-half-lakh people at the first stage. Govind, whose muscular and idiomatic Hindi is palpably better than his English, topped the list of Hindi-medium candidates this year. One in four now prefers to take the exam in Hindi, or a regional language. Their success rate is far lower than that of English candidates, but still, their numbers are rising.

And then, of course, there is reservations. The 27 cent per cent reservation of seats for OBCs since the mid-'90s, in addition to the 22.5 per cent reserved for the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, has begun to radically transform the composition of an upper caste-dominated higher bureaucracy. There may be unfilled quotas in the lower services, but in coveted services like the IAS, IPS and IFS, they are intensely sought. OBCs, especially, are boosting their representation in these top services by making it to the general category. According to the Department of Personnel, in the last five years, 32.5 per cent of officers inducted into the IAS have been OBCs.

The impact can be seen in the individual stories of young men and women who are among the first to represent their communities in the bureaucracy. For example, Sudha Devi, a young additional commissioner in the Himachal cadre, is the first woman from her Kangavellalar farming community in Tamil Nadu to make it to the IAS. Says Sudha, "My getting in has been an eye-opener for this area and my community—so many others are preparing now. Every time I go home,girls come to me for counselling."

One of eleven children of a former powerloom worker, now grocer, in the communally sensitive textile town of Malegaon, Maharashtra, he went to school there, then did his Masters from Pune. He joined a civil services study circle for backward and minority students at Hamdard University in Delhi.

"I have seen the lack of resources on the ground, no proper hospital, or colleges.... I see my IAS job as that of a middleman, between the government and the people, and I feel responsible towards all the people, not just those of my community."

Yet, despite reservations, the poorest seem to be largely excluded from the civil service club (as are Muslims). The social data shows that only a minuscule number of the new babus are first-generation learners. The number has declined since the '80s. The number of those educated in government schools is steadily going down (which reflects loss of faith in state education). A commission headed by economist and educationist Y.K. Alagh on civil service recruitment, which submitted its report to the government in 2001, was concerned at these trends. Speaking to Outlook, Alagh reiterated that concern: "A munsif's son is good, but a landless labourer or an artisan's son even better. Half of the country's workforce are landless labourers."

The Alagh report blames government policies that have relaxed age limits and the number of chances available to candidates. It says they favour crammers who spend large sums on coaching (about a lakh of rupees a year, per candidate), and perfect exam-taking techniques, making it harder for bright, poor candidates in all categories to get in. Agrees Planning Commission member B.N. Yugandhar, "Coaching makes it very difficult for first-generation learners to get in."

Age is a touchy issue. At 30 years for the general category (33 for OBCs, 35 for SC/STs), the age limits are among the highest they have been. Correspondingly, the number of new recruits over 26 has been rising steadily, upsetting the bureaucracy, which says older candidates are harder to train, and get frustrated because they don't reach the top due to shorter tenures. In February, then cabinet secretary B.K. Chaturvedi wrote to the PMO, recommending 24 as the age limit for the general category, which is what it used to be in the '60s. Says Satyanand Mishra, secretary, personnel, "Age levels have been increased in deference to the demand that a lower age of recruitment works against people from rural areas. But empirically this is not true—reducing age limits will not handicap any class of people." But for the political class, this is a hot potato. And for the Sanjay Singhs and other denizens of places like Mukherjee Nagar and Hudson Lines, a death blow. "Higher age limits are good for people like me—we work, make money, keep trying, get in," says Sanjay Singh.

Notwithstanding the distaste of reform-minded committees for coaching—and for an exam that has become a byword for narrow, tactical swotting—many civil servant recruits interviewed by Outlook, from small towns and villages, and relatively modest backgrounds, have a different perspective. They see coaching as the leveller that flattens the playing field, helping them compete with the better educated and the socially confident.

For families, coaching is an investment—land is sold and money borrowed to pay for it. Interview coaching, especially, is a must—this year's topper, Muthyalaraju Revu, travelled to Delhi's coaching hub for interview coaching. Says Govind: "It teaches you to be balanced, to keep your ego in check, to come across as energetic and confident." Those understandably petrified of confronting the retired bureaucrats who dominate interview boards are told, "Behave as if you are going to meet your new family."

And so they make it, finally, to their "new family". But are the new recruits improving the quality of a rather discredited family, often perceived as lacking in accountability, efficiency and integrity? It is hard to generalise—talking to a cross-section, you will encounter the blazingly sincere and the rather cynical, the confident and the diffident, the rock-solid and the showy. Says social activist and ex-IAS officer Aruna Roy, "Many take big dowries, contravening the act they implement. Some are susceptible to community and communal tendencies, which is not surprising, if you look at the distortion of history and values in current-day education, especially in the Hindi belt—many don't know history." She also worries that there are "no role models left to show young recruits they need not bow to political pressure".

On the other hand, asserts Roy, "They are far more rooted in the reality of India than my generation of civil servants. India is very complex now and they understand that complexity better than we did—some have a very genuine awareness of landless, Dalit and minority issues." Agrees Alagh, "Their being in the bureaucracy is an important part of the building of modern India. Despite the homogenisation that takes place when they become part of the elite, they are not the bureaucrats you see at embassy parties. You can tell a JNU district collector a mile off. They can sort out the problems of real India. "

Down on the ground, Anbukkumar, though he is already getting a good reputation in the district where he works, makes no such claims. "To be frank," he says, "I have no big vision or ideals as such. I had no idea of policy-making or decision-making or file notings. IAS simply meant a red-light car and a lot of power. I am slowly learning the ropes now. I may not become the number one IAS officer, but I want to be fair and just. No more dreams, no more ideals. Slowly and surely, I will evolve."

By Anjali Puri with Sugata Srinivasaraju and Madhavi Tata

Tags