Can A $1 Billion WB Loan + Rs 11,500 Crore Stop All This?

A River Less Gung-Ho

The much-sullied Ganga receives fresh funds and attention

1. Illegal Mining

Example: Haridwar In and around the town, boulders abutting the river are being removed for construction, causing damage to the river's banks and bed. Tractors and trucks often just drive through the bed in the dry season.

2. Climate Change

Example: Devprayag The melting of the Gangotri glacier, the source of the Ganga, has accelerated. This could impact water flow in the river in dry seasons, specially in Devprayag where around 30 per cent of the water flow is from melted snow and glacier. One controversial estimate says the glacier may disappear by 2035.

3. Ill-Planned Dams

Example: Downstream Uttarkashi Over 600 dams are either operational, under construction or being planned along the rivers Alaknanda and Bhagirathi, that combine to form the Ganga at Devprayag. Besides causing great damage to the geography of the region, the dams obstruct the natural flow of the river, thus reducing the oxygen content in the river. A lack of it is killing many of the living organisms that are key to ensuring the health of the river.

4. Untreated Sewage

Example: Kanpur Untreated sewage is a big problem all along the river from source to sea. Tanneries in Kanpur have been dumping waste into the Ganga. Only about a third of the sewage and industrial effluent being discharged into the river is currently treated.

5. Sewers & Waste Water Canals

Example: Calcutta Twenty-six major and numerous minor nallahs flow into the Ganga in Bengal. The sewage treatment plants do not function effectively. According to experts, the water of the Ganga is not even fit for bathing in Bengal, Varanasi and most major cities along the river (see map). Along with industrial pollution, untreated sewer water is a major problem.

6. Body Dumping

Example: Varanasi Half-burnt bodies are washed away in the river. Some bodies, like those of sadhus, are traditionally thrown into the river and not cremated. Around 35,000 bodies are cremated on the ghats in Varanasi every year. An electric crematorium set up in 1989 is in a state of disrepair.

7. Animal Extinction

Example: Bhagalpur Irrigation barrages and pollution are endangering the ecosystems of the Ganges River Dolphin, along hundreds of kilometres of tributaries all along the Ganga. Less than 2,000 remain.

***

There is a lot to mend if the government’s target of a clean and free-flowing Ganga by 2020 is ever to be achieved. Can India realise this ambitious goal, especially with its inexcusable failure in cleaning the Yamuna? With the Rs 15,000 crore that the government started spending in 2009 to ensure that no sewage and industrial waste goes untreated into the Ganga, it will require ingenious planning to ensure all this money is not washed away as well. The World Bank, which signed a deal with the government on June 14 to pump in over a billion dollars to save the river, has been rightly cautious—given the past errors. However, the bank has been encouraged this time by a changed approach that treats the river basin as a whole instead of isolated programmes for each city along the river. Other improvements over the past include ongoing maintenance to ensure treatment plants and other assets keep working, the creation of strong operational-level institutions at the Centre and the states to effectively manage the programme and a stress on broad-based stakeholder participation.

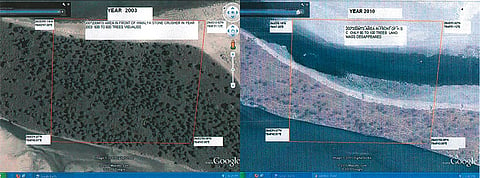

Union minister of environment and forests Jairam Ramesh, who leads the onerous charge of saving the Ganga, is frank enough not to guarantee complete success (see interview). Yet, there seems hope this time around as thousand-crore dams are scrapped, and the Centre threatens, for the first time, direct action if chief ministers of riparian states along the Ganga basin fail to act. Uttarakhand chief minister Ramesh Pokhriyal Nishank, for instance, has been getting quite a few missives from the Centre for his government’s repeated, and some would say intended, failure in cracking down on illegal mining in and around the Ganga. As riverine islands began disappearing, something the swamis prove with great alacrity using Google Earth’s satellite images, Matri Sadan launched its steadfast campaign. It was not the first time Nigamananda went on a fast; he had done so on many occasions. It was finally after a protracted battle, involving government orders banning mining that were stayed by the high court in Nainital on appeal by miners, that Matri Sadan won a favourable verdict that still stands.

On May 26 this year, the court asked the Uttarakhand government to implement a ban on mining and stone-crushing immediately in the area where the Kumbh mela is held at Haridwar. However, Brahmachari Dayanand of Matri Sadan says, this was not before the government tried reducing the Kumbh Mela area by illegally reintroducing a 1992 government order which earmarks a smaller region. After strong opposition from the sants, it was overruled with a new one in 2010 to include the larger stretch along the river.

A short drive from the ashram leads one to the spot where mining has gone on for years, leaving gaping holes in what was once agricultural land along the banks and hastening the erosion of the Ganga’s banks. Typically, boulders are excavated from the riverbed, crushed and then piled on to trucks that feed India’s insatiable construction frenzy. The bed becomes a road as tractors and their trolleys are driven across in lean, relatively drier seasons, threatening aquatic life. “They have been ripping apart the river’s womb, tearing apart her chest,” says Dayanand. The machines are lying quiet at present but are likely to start again, drowning the river’s restful gurgle with their roaring chorus.

Facing strong opposition against dams, the central government has declared the 135-km stretch from Gaumukh to Uttarkashi as an eco-sensitive zone, preventing the construction of any dams. Ordered by the MoEF, IIT-Roorkee has also submitted a cumulative impact assessment report of 69 dams in Alaknanda and Bhagirathi in March. It is on the basis of this report that the ministry is reworking to make its past clearances stricter. But Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People says that the Roorkee report does little to save the Ganga from dams and has a “pro-dam” bias. Instead of excluding the now-scrapped hydropower projects in the eco-sensitive zone, the report lists them as those under construction. “It even tries to build up a case for restarting work on these projects,” he says.

The other half of the cumulative impact assessment of the dams on the upper reaches of the Ganga is being carried out by the Dehradun-based Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and deals with their impact on the riverine biodiversity and ecosystem. In its interim report, the WII has said that certain dam projects, especially Kotlibhel IB and II, are likely to have irreversible impact on the ecosystem that supports mammals like wild goat, antelope and barking deer, and fish like mahseer and snow trout. They would also adversely affect the migration pathways in the region. Based on this report, the Forest Advisory Committee withheld the forest clearance for the Kotlibhel IB and II dams in May this year. Thakkar points out the stark divergence between the two reports. “While the WII one concluded that the Kotlibhel 1B, Kotlibhel 2 and Alaknanda Hydro projects should not be built due to their impact, the IIT-Roorkee study just mechanically calculates environmental flows (minimum water required to maintain a healthy ecosystem in a river) and implicitly says construction can go ahead.”

The problem of sewage disposal has been exacerbated due to poor planning across the Ganga’s course. This is the case in upstream Srinagar where the sewage pipes laid down were just six inches wide, often resulting in blocks. Because of this, few in the town have joined their sewer lines with the community one fearing frequent blockages. The sewage is, therefore, released untreated into the river.

In Varanasi, the creaking British-built main sewer line leading to the treatment plant is on a higher gradient than many of the feeding pipes laid later as the city grew congested along the banks of the river. Consequently, the government always needs to pump the sewage up into the main line, which might seem like a perfectly workable idea but isn’t. Very often, there are power cuts, and the pumps, which are located near the river, do not work, resulting in the sewage flowing back into the pumping stations from where they are let off into the river. “And during the monsoon, rising water from the river, along with silt, inundates the pumps. So, they are shut for five months every year officially because of flooding and the required cleaning,” says Veer Bhadra Mishra, president of the Sankat Mochan Foundation in the city that runs a ‘Clean Ganga’ campaign.

In Calcutta, even the treated water fails to meet expected standards. Arunkanti Biswas, who was with the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute’s zonal laboratory here, says that sample tests of water from 141 of the 325 outlets that discharge treated water found the treatment to be faulty. In most cases, the “biochemical oxygen demand” or bod value fell short of the specified 3 ml per litre in properly treated water. Sujit Bhattacharya, former chief engineer of the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority, thinks past efforts at cleaning the Ganga have been “a total failure” for a number of reasons, from lack of expertise in handling wastewater treatment to mismanagement of funds.

But as government authorities appear to shake off their stupor to clean up the Ganga, Jairam Ramesh stresses part of the challenge is also to get Indians to genuinely respect the holy river. “India is a country where individual hygiene and collective squalor coexist. We say it’s a holy river but look at the way we treat it. In fact, we are comfortable with this squalor and add to it,” he says. In Varanasi, people soap themselves in the Ganga despite notices asking them not to do so, offerings in plastic bags crowd the banks and refuse from funeral pyres line the river’s edge. Unless we change the way we treat our rivers, can we expect the government to clean up all our filth that the Ganga washes away quietly, day after day?

By Debarshi Dasgupta in Srinagar (Uttarakhand) and Varanasi with Dola Mitra

Tags