Pilgrim’s Repose

An ancient Indian link to the holy land stands firm amid all the turbulence

- The Indian hospice, called Zawiya al-Hindiya, stands on 7000 sq m of prime land in the historic heart of Jerusalem’s walled city

- It is built on the site where Sufi saint Baba Farid stayed in the 14th century

- Since 1924, the hospice, which flies the Indian tricolour, has been run as a charitable trust by a family whose ancestor came from Saharanpur. They remain Indian citizens.

- It has hosted Indian soldiers during World War II, India-Palestine meetings in recent years

- It still offers rooms to visiting Indians of all faiths

***

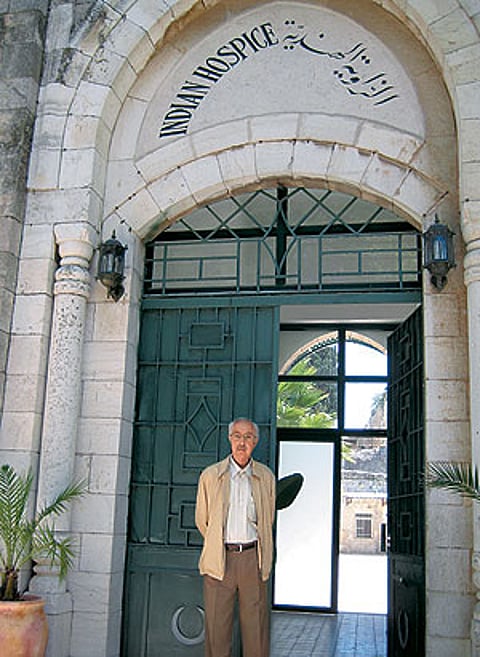

Sheikh Mohammad Munir Ansari at the Indian hospice in Jerusalem |

It is an old Indian connection, going back more than 700 years—to a visit by the Sufi saint Baba Farid, who came to Jerusalem while on a journey of exploration of Islam. In a gesture of respect, the governor of the Ottoman Empire offered him hospitality inside the Islamic precinct and the two rooms where he stayed became a holy site for Indian pilgrims over time, eventually expanding into the impressive Indian Hospice or Zawiya Al-Hindiya as it exists today. Inside the walled city, near Herod’s Gate, the compound is a short walk from Jerusalem’s holiest sites.

In the early 1950s and ’60s, the place buzzed with hundreds of pilgrims, families packed into a room, eating and enjoying chai in the serene courtyard. They would come on their way back from the Haj, equipped with their holdalls and supplies of rice and dal. During World War II, the hospice served as a leave camp for the 4th Indian Division of the British Army, with tents for the soldiers pitched all around the building.

More recently, the hospice was the location for a meeting between former foreign minister Jaswant Singh and Palestinian leader Faisal Husseini in 2000, after the Israelis made it difficult for the delegations to meet at the designated spot. A part of the compound houses a UN medical centre for Palestinian refugees, providing crucial services to thousands of displaced people. The brown stones of the two-storey hospice buildings have witnessed much history, but the Indian thread has never broken, despite the wars and devastation, the uber politics and religious rivalries of the area.

The proud custodian of this mini Indian empire is Sheikh Mohammad Munir Ansari, a soft-spoken patriarch. The hospice was set up as a charitable trust and has been supported by the Indian government since Indian independence. Support channels from Delhi may have occasionally been blocked but they never dried up. The Ansari family, which retains its Indian identity and nationality, has politely declined repeated offers of “help” from Israelis and Palestinians because of possible complications. “Too many eyes are on this property,” says Nazeer, the sheikh’s son, a civil engineer who helps his father manage the affairs of the hospice. He recalls how someone dug a tunnel into one of the unused rooms and was evicted only after the family informed the Indian embassy. Their Indian identity gives the Ansaris some immunity and protection from local politics, but they still have to remain vigilant. “We stay absolutely away from local politics or we won’t be able to live here.”

Sheikh Munir inherited the mantle from his father, Sheikh Nazer Hassan Ansari, who came to Jerusalem in 1924 from Saharanpur to administer the hospice at the request of the Grand Mufti of Palestine. He slowly expanded the property, travelling regularly to India to collect funds. He brought his Indian wife over but later also married a Palestinian. Sheikh Munir, who was born of the second wife, is married to Ikram, another local from a prominent Jerusalem family. Even so, the Sheikh and all his five children carry Indian passports.

“It is mercy from God. I feel I belong to India more than to an Arab country even though I was born and brought up in Jerusalem,” says Sheikh Munir, sitting in his office adorned with daguerreotypes of the leaders of the Khilafat movement and the Nizam of Hyderabad, and photos of Gandhi and Nehru. His eyes twinkling, he tells the story of how he learnt Hindustani from an Indian captain in exchange for teaching him Arabic when Indian soldiers stayed here during the period of the British Mandate. “I remember there were separate kitchens—one for Hindus and Sikhs and another for Muslims and Christians.

The Indian soldiers helped build the Travancore and Delhi wings to the complex. But it is the Ansaris who have been key in establishing and maintaining this Indian “fact on the ground”. It was never easy and today the hospice is ringed by armed Jewish settlers, including one who shoots when challenged. The demographic war between the Jews and Arabs for control of Jerusalem rages all around this oasis of calm.

The family has paid a heavy price for it all. Sheikh Munir lost his mother, a sister and a nephew in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war when the hospice was bombed. “On the third day, the Israelis entered the old city, but before coming in they wanted to clear the way. Twenty-seven mortar shells fell on our hospice while we were hiding in the basement,” he recounts. Jerusalem went from Jordanian to Israeli control and the hospice was heavily damaged. Since India did not have diplomatic relations with Israel at the time, it was difficult to send help. The 12 shops in the city built with an earlier Indian grant brought in rent for the Ansaris during this difficult period.

Sheikh Munir kept in touch with the Indian embassies in Cairo and Amman, but faced with shrinking resources he had to rent a part of the compound to an Arab primary school for several years. The situation improved in 1992 when India established relations with Israel, making communications easier with New Delhi. Moral support and financial help now flowed readily.

Sheikh Munir says the just-retired foreign secretary Shiv Shankar Menon, who was India’s ambassador to Israel from 1995 to 1997, played a crucial and constructive role in opening new channels. “He believed in the hospice and supported the rebuilding. He got all the plans approved.” An old mosque and a few guest rooms have been renovated but more work is planned. Menon also invited the Sheikh and his son Nazeer on an official, three-week trip to India, complete with lavish hospitality as a gesture of thanks. They remain friends to this day.

It is a difficult and delicate task to maintain this unique Indian presence in Jerusalem, a fiercely disputed city whose final status will be decided only when there is peace between the two sides. But armed with nothing more than the diplomatic finesse and strategic thinking that has helped them survive all these years, the Ansaris look to the challenges of the future with confidence and equanimity.

Tags