Magnitude 9 On Mind’s Richter

Earthquake, tsunami, N-meltdown. All at once. Faith in science, orderliness lies shattered.

The town of Ookuma has 11,000 people living amid large swathes of farmland dotted with hamlets. The Oogas lived only 4 km from the Daiichi nuclear power plant, where currently four of the six reactors have experienced hydrogen explosions and a team of technicians are courageously grappling with partial meltdown. Should the nuclear crisis exacerbate, it would prolong manifold the misery of Japan, already reeling under the havoc of the earthquake and tsunami. The official death toll stands at 5,500, over 8,000 are still missing, and the total loss has been pegged at a numbing $184 billion.

A nuclear crisis was the nightmare the Oogas had feared and now share with millions of compatriots who watch with horror as their lives, that only a few days before comprised cutting-edge technology and seemed defined by foolproof efficiency, now crumble before their eyes. “This is the worst crisis faced by the Japanese since the end of World War II, when the country was in ruins,” says Atsushi Yamada, a journalist at the Asahi newspaper. He says the unfolding catastrophe is a wake-up call for the Japanese, who, after decades of prosperity, are now acutely aware of “our vulnerability to nature and national pride in our technology takes second place”.

The Japanese emperor, in a recent statement, spoke of the need for “overcoming this unfortunate time...by caring for other people”. The massive crisis has prodded people to review their affluent lifestyles. Ooga, now waiting desperately for better news, agrees wholeheartedly. For the past six days, living with her friend in Tochigi, around 100 km from Fukuoka city, the conversations over the dinner table have been about how they can work harder to make Japan a better place for its people. “The saddest aspect of the nuclear disaster facing us is that we could have avoided it,” Ooga says.

She says the local people accepted the nuclear plants in the area in the 1970s because they thought the technology represented long-awaited modernism and a big, vital step towards economic development. “But that’s not what we are thinking now,” she points out. “The bittersweet lesson today is that the era when rich companies were given priority for the sake of economic expansion is over.”

Analysts say the public mood, as represented by Ooga, refers to the heady days when Japanese companies such as Tokyo Electric Power Company, Japan’s largest utility firm and operator of the damaged nuclear power plants, along with the government directed with gusto a miraculous postwar economy recovery. Tens of millions of ordinary Japanese were educated and employed, producing an army of qualified, committed people, mostly men in navy blue suits who worked late hours and collaborated closely to produce the cutting-edge technology that made their country the second richest in the world—till China overtook them two years ago.

Prof Yoshimitsu Shiozaki, expert on disaster reconstruction at Kobe University, says the present situation is the worst Japan has ever faced. “Never has there been a disaster that has so many aspects to it. Today, Japan is faced with picking up the pieces from a huge earthquake, unprecedented tsunami and a worsening scenario from nuclear plant accidents, a situation that will change the country forever.”

For sure, it will take years for Japan to stage a recovery. Shiozaki makes this projection based on the experience of Kobe, a bustling port city in the west, where an enormous earthquake left 6,000 dead and shattered the infrastructure. Says the disaster expert, “We have wide stretches of northern coastline, cities and villages devastated by the temblor and tsunami. We are also facing a situation where thousands of people could be contaminated with radiation. This means massive reconstruction efforts are needed to put everything back to normal.” Since Kobe took almost a decade to recover, Shiozaki says, “I am now guessing that what we face today calls for decades of mindboggling planning and unwavering commitment among the Japanese people to make a recovery.”

He says various challenges will start emerging within a month. With almost 90 per cent of the national population living on the coastline, given the mountainous terrain of the archipelago, Shiozaki says the devastation caused by the tsunami demands construction of new buildings, houses and infrastructure that can withstand such future disasters. Other challenges cited by experts include the aging population, with mounting medical needs, and the national debt, which sets financial limits to recovery efforts. Despite the ample liquidity injected by the central bank to protect the banking system, and the government’s insistence that the basis of the economy remains sound, investors seem to be losing confidence, reflected in the rapid selling of Japanese stocks. Predictions point to austerity bracing for the population and a picture where the capital Tokyo, hit by power cuts that have slowed down business activities heavily, must rely on the less affected Kansai, or the western region of Japan, to play the role of an engine of the national economy.

For now, the country is faced with helping the affected population settle down, first in the evacuation centres and then to slowly return home. Almost one week after the quake, there are reports of people still marooned in their homes with no aid, a situation that is shocking, comments Shiozaki, given the easy availability of helicopters and ships in the country. Another disappointment for the public is widespread mobile phone jamming that has left hundreds of thousands of people unable to reach out to each other. Television footage shows heart-rending searches by families crying out to their loved ones or looking intently for even traces of them among mountains of rubble which were once offices or homes.

Analysing the aftermath, Dr Yasuo Kawawaki, head of the Japan Recovery Platform, points out that the death toll has been limited because of the strength of the buildings that are strictly regulated—for instance, almost all houses or buildings held strong in Tokyo, which also experienced a quake of magnitude over 5. “But the tsunami is a different story,” he says. Japanese earthquake safety standards are maintained for tsunamis of up to four metres and quakes of Richter 8 magnitude. The tsunami waves that lashed the coastline measured nearly 9-10 meters.

Still, what remains inspiring, apart from much of the sound construction on display, is the relative calm witnessed among the survivors—long, orderly lines of people waiting for food and water and ready sharing of blankets till more supplies arrive. There are no reports of looting or angry protests, which illustrate some examples of the culture of patience and stoicism that help enormously at times of disaster and in recovery. “Now comes the time when we must pull ourselves together to rebuild once again a new country,” insists Yamada.

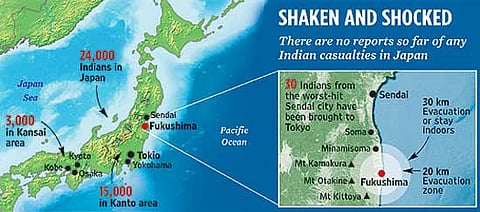

Indians In Japan

- In 1873, a few Indian business families settled in Yokohama and Okinawa

- Yokohama and Kobe have Indian communities, mostly engaged in textiles, jewellery, auto, import-export.

- Yokohama also has an Indian school

- Other cities have floating population of Indian IT experts, students, factory workers

- There’s a large population of Indian cooks in Japan, working at Japan’s many Indian restaurants

- Some 70 Indian IT firms are based in Tokyo, including TCS, Infosys, Wipro, L&T

- The Indian embassy opened a culture centre in 2009

Rescue And Relief

- No reports of any Indian casualties

- No travel advisory issued by New Delhi. Individuals to decide whether they want to leave Japan.

- Air India is flying Boeing 747s, instead of 737s, to bring those who want to return home

- India has offered 25,000 blankets to Japan. Also a search and rescue team, but Japan has not accepted it.

(Suvendrini Kakuchi is the Tokyo correspondent of www.ipsnews.net)

Tags