Fistful Of Dissent

Can the incipient people's movement threaten the dictator?<a > Updates</a>

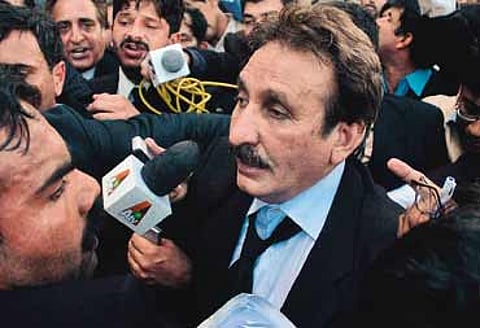

A movement, however incipient, has been born, a movement that's as much a protest against the general's arrogance as it is in support of Chaudhry. Lawyers countrywide are on strike, a handful of judges have resigned, as has the government's deputy attorney general, Nasir Saeed Sahikh, who said, "I cannot work in this system, particularly in the ongoing crisis."

Clearly, by refusing to succumb to Musharraf's pressure, Chaudhry has created an ever-growing territory of dissent. Politicians who met Chaudhry in the days following March 9 narrated to the media his version of what had transpired in the five-hour meeting between him and Musharraf. For instance, former law minister Syed Iftikhar Hussain Gilani told Outlook, "I met him twice at his residence and once in the court. He revealed that the president had given him two options, either to resign and the government would take care of him which meant he would be accommodated in some lucrative post, and second, to face the reference. Chaudhry told Musharraf that he would face the reference." Such stories enhanced Chaudhry's stature, turning him overnight into an example of dignity and defiance, a necessary corrective, in the form of an independent judiciary, to an authoritarian regime.

Not that Chaudhry, a son of a mere policeman in Balochistan, needed such props to enhance his stature. Popularly known as the 'people's judge', he worked overtime to clear the massive backlog of cases in the Supreme Court, never hestitating to step on the toes of the rich and the powerful. Whether it was saving a public park that was to be converted into a golf course or with ecologically aware decisions like nixing the plan to build a New Murree city, or issuing suo motu notices in favour of the poor, Chaudhry had blazed a trail for judicial activism. He even annulled the government's plan to privatise the Pakistan Steel Mills, saying the decision had been taken in "indecent haste".

But what earned him accolades from the people, and the ire of the government, was his response to those agitating outside the Supreme Court demanding to know the whereabouts of their missing relatives. Known here as "disappeared people", their numbers run into hundreds. Chaudhry asked the government to explain these disappearances. As the Friday Times wrote in its editorial, "His worst crime was his insistence on enforcing the writ of habeas corpus in favour of hundreds of persons who had been abducted by the secret agencies of the military and confined without due process of law.... This was anathema to the establishment which has got used to its unaccountable and domineering status."

Many find it bewildering why Musharraf should have taken on an independent judge such as Chaudhry. But then Musharraf had his own compulsions. Wanting to get himself elected for another term by the current electoral college (members of Parliament and the four provincial assemblies), he was apprehensive of the Supreme Court under Chaudhry admitting a possible petition asking him to renounce his uniform. Pervez Hoodbhoy, who teaches at the Quaid-e-Azam University, explains why it's crucial for Musharraf to simultaneously wear the two hats of president and chief of army staff: "Men who live by the gun are willing to die by the gun, and Musharraf is not taking chances. He knows the real threat to his power—and his life—comes from within his constituency, the military. As a result, he has become obsessed with micro-managing everything from troop movements to postings and promotions, all of which require his personal stamp of approval."

The government, obviously, had not bargained for Chaudhry's spunk, or the response of lawyers, who otherwise haven't had a defining role in the history of popular protests here. Columnist Ayaz Amir wrote, "How different this time: Blackcoats in front, first at the barricades, the nation behind, drawing inspiration from their courage and example. My Lord the chief justice is thus proving to be a catalyst of a larger discontent. All the issues swept under the carpet for the last seven-and-a-half years are coming into the open".

Human rights activist Asma Jehangir says the fervour of lawyers is more a reaction to the military rule than anything else. "Pakistanis have matured. They can clearly see through the hypocrisy. The lawyer's movement has acquired a broader agenda, addressing the survival of civil institutions under the weight of militarisation. Their support has widened, not out of love for the judiciary, but because of the shared abhorrence of military rule," she told Outlook.

This impulse may prompt those fighting for Chaudhry's cause into further embarrassing Musharraf. For instance, Chaudhry's chief defence counsel in the SJC, Aitzaz Ahsan, says he plans to call Musharraf to the proceeding and ask him to explain the real motive behind the reference. "I should be allowed to cross-examine him on oath in an open trial. If an US president can do so, why shouldn't the referring authority here be subjected to the same treatment?"

But ennui might set in as the council's proceedings are expected to drag on for months, consequently dissipating the popular anger against Musharraf. This problem is compounded by the disarray among the Oppositon. Some are hopeful of Benazir Bhutto providing a direction to the movement. On March 21, she flew down to London from New York to meet former PM Nawaz Sharif, in the quest to evolve a strategy to bolster the anti-Musharraf movement.

Indeed, this could be Pakistan's tryst with destiny. Says Hamid Khan, another counsel for Chaudhry, "God forbid if the dictator succeeds in his designs, our country will be in a state of turmoil. We must join hands to avert that. I would request the judges not to succumb to any pressure. If they can't rise to the occasion, anti-democratic forces will become stronger and people will lose confidence in the judiciary."

Should the SJC withstand the immense pressure of the establishment, Musharraf could suffer from prolonged bleeding. Couldn't he beat a retreat to defuse the crisis? In such an eventuality, not only would his prestige suffer irreparably (some already call the crisis Judicial Kargil), but he must be prepared to doff his uniform, allow exiled politicians to return and swear in an interim government to supervise a free and fair election—these have to be the concomitant aspects of a retreat.

No wonder senior political analyst Nusrat Javeed is optimistic, "The improper removal of the chief of army staff (Musharraf) on October 12, '99, unravelled the democratic structure of Sharif and led to his downfall. The improper removal of the chief justice might unravel the military's hold over Pakistan."

Tags