Desert Phoenix

The Mughal sire's grave has been roused from the cinders of war

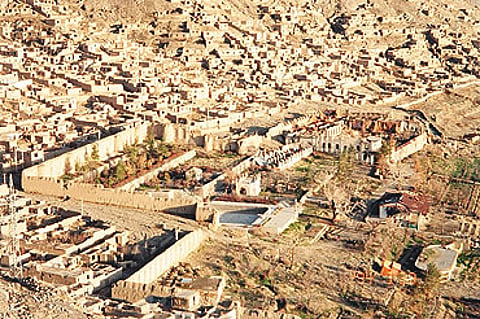

The Bagh-e-Babar began as a natural wilderness spread over 11 hectares. Always longing for Fergana, the small kingdom in present-day Uzbekistan that he lost when he was 13, Babar tried to recreate its beauty wherever he went, building gardens in different parts of his growing empire, and introducing new plants and fruits to the regions he conquered. Unlike the highly stylised gardens of the later Mughal rulers, Babar's gardens were more natural pieces of land reclaimed from the wilderness and transformed with some ordered plots, flowers, fruit trees, and watered by streams. His attention to detail in the creation of his gardens is recorded in his memoirs, the Babarnama. "It is necessary to make geometrical grass plots and plant some flowers with nice colours and scents around the edges of the grass," Babar notes. But his favourites always remained his gardens in and around Kabul, the kingdom he conquered in 1504. His memoirs describe how in his garden in Kabul he had "a spring surrounded by stonework into a ten by ten pool, such that the four sides would form benches overlooking the grove of Judas trees. When the trees blossom, no place in the world equals it". On his death in 1530, Babar was first buried in Agra until, at the urging of his Afghan wife Bibi Mubarika, Humayun brought the remains to his garden in Kabul, fulfilling Babar's wishes.

In succeeding years, during visits to Kabul by later Mughal kings, including Shah Jahan, the Bagh-e-Babar became more structured and formal, with walls and water cascades added. More structures were built in subsequent years. The pavilion and the queen's palace were built by Amir Abdur Rahman Khan at the end of the 19th century but cut into the original design of the garden, including the central axis. The central water channel was disrupted. During the Soviet era, a swimming pool was built inside the garden as well as a greenhouse in an attempt to make it more of a public space. The garden suffered its worst blow in 1992-93 when bombing destroyed the water systems. Though these were restored in the mid-'90s, the original trees had died by then.

While past archaeological surveys provided some information about the original garden, old foundations like that of the Shahjahani gate were discovered during the ongoing restoration, as was the central water channel. For the enclosure of Babar's grave, an 1852 drawing by Charles Mason which was found in the British Library was used to recreate the original. For this work, the marble was brought from India, and Indian craftsmen were used to create a replica, which was assembled in spring this year.

Sixteen species of plants mentioned in the original Babarnama have been replanted in the Bagh-e-Babar—planes, apricot, apples, peaches, quince, pomegranate, hawthorn, cherry and argowan (judas) trees. Traditional Afghan building techniques, including the use of hand-laid earth (pakhsa) and sun-dried bricks on stone foundations, have been used, as have their methods of mixing lime and making load-bearing arches.

But while tradition has been resurrected, the garden's restoration also reflects contemporary needs. The Shahjahani gate, for instance, will now become a public reception centre. The Soviet-era swimming pool, an eyesore in the original design, has been shifted just outside the perimeter and will provide valuable revenue for the garden. The queen's palace has been redeveloped—it has already hosted the performance of a Shakespeare play. As the Bagh-e-Babar regains its former glory, providing balm for the soul of this bruised and battered city, Babar can rest easy in his grave again.

Tags