Why Don’t They Take Saccharine?

Drought, politics, a mills vs farmers feud have shot up sugar prices

- Farmers seeking better returns for cane

- Centre’s suppression of minimum support price (MSP) has seen states fix higher tariff

- Farmers fear Fair and Remunerative Price (F&RP) mechanism will work against them

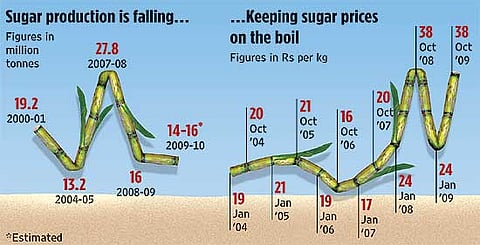

- The sharp dip in domestic sugar production leads to rise in imports. Consumers will have to pay up to and above Rs 40/kg.

- Delay in harvest of sugarcane will result in late sowing of wheat by hundreds of farmers, which will adversely affect India's foodgrain production this year

***

A father of three school-going children, Amarjit owns a little over an acre of land. The regret over not having sold his entire cane produce to jaggery units earlier, when the rate was Rs 200/quintal, is evident. “First the crop is poor, and the price is bad, and then the government is fighting at our cost. Why should we grow sugarcane?” asks the 45-year-old farmer. As if to bear him out, sugarcane production in UP is 15-20 per cent lower this year.

Anomalies of sugar production have always been politicised, particularly in Uttar Pradesh. This factor is again at play, now that farmers and sugar mills are at a bitter standoff. Worryingly for consumers, the sugar shortage is threatening to further push up retail prices from the current levels of Rs 38-40 per kg—already double the 2007 prices.

It all began in October, when the agriculture ministry introduced a fair and remunerative price (F&RP) mechanism for sugarcane, replacing the minimum support price (MSP), and let the market determine the cane price. However, despite the sugar shortage and high retail price, when UP mills initially signalled that they would not pay more than the suggested F&RP price of Rs 129/quintal, farmers protested on the streets. With the political tempo rising and threatening to spill over to Parliament when it reconvenes on November 19, Union agriculture minister Sharad Pawar has striven to persuade UP mill owners to pay more than the state-assured price (SAP) of Rs 165-170/quintal. The farmer groups are, however, demanding at least Rs 215/quintal.

Notwithstanding cyclical ups and down, cane price politics has been a major culprit behind the sharpest dip in sugar production this year, from 27.8 million tonnes in 2007-08 to 16 million tonnes now. The coming year too the production is likely to be 14-16 million tonnes as against a demand of 23 million tonnes, leaving a wide gap for imports. Of the total domestic demand, industries consume 70 per cent.

“Despite costs of sugarcane production in UP having risen to Rs 155 per quintal and more, if we add the risk premium and a normal 10 per cent profit, the mills are not willing to pay adequate price. The result is farmers are shifting to other crops not because of expected profits from them but due to losses in sugarcane,” points out Sudhir Panwar of Kisan Jagriti Manch. Thanks to the white grubs pest in UP, pesticide inputs have gone up too. Given the higher input costs, H.L. Singh, agronomist at Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel University, Meerut, feels, “Price must be an incentive to farmers to continue production. Currently, the situation is not conducive.”

Experts stress that other than inadequate compensation, around 70 per cent farmers have to wait for over a year sometimes to get full payment for their produce. Presently, everyone is waiting for the standoff to end. Following talks on November 10 with UP Sugar Mills Association (UPSMA) members, Sharad Pawar informed the media, “I have told mills not to create a situation where farmers will be forced to switch to other crops.” A quick solution is critical: sowing time matters for wheat yield. If sown by November 10, a farmer can expect around 15-16 quintal per acre yield. But if sowing is delayed till December, wheat production can drop to 10-12 quintal/acre.

Sugarcane farmers in the north normally sow wheat after two, and sometimes three seasons of harvest, before sowing a fresh cane crop around April. Unlike wheat or rice, sugarcane cannot be harvested and stored as it leads to loss of quality—the cane dries up with time. Indicating that the UP mills will start crushing by third week of November, UPSMA chairman C.B. Patodia told Outlook, “No decision has been reached so far with the farmer groups. Ninety per cent of farmers are willing to sell us the produce but the issue has become political.” With the state and central government throwing back the ball in the UPSMA’s court, the mills may have to pay more than the SAP of Rs 165-170 a quintal.

Driven to suicide or burning of stock in some cases, farmers may not be willing to settle for the SAP—given the higher input costs and rising sugar price. “Any price below Rs 215 will neither be remunerative nor fair,” says Anil Singh, secretary of the National Alliance of Farmer’s Associations (NAFA). In a representation to the prime minister, NAFA has alleged that faulty government policies—particularly the 3.3 million tonne sugar exported till February 2009 despite all indications of an impending domestic sugar shortfall—has led to India having to import raw and refined sugar when global prices are rising.

This is no different from wheat mismanagement two years back, which led to a shortfall necessitating imports at high costs to soften domestic prices. In both cases, consumers have had to pay a heavy price while farmers were being systematically denied the incentive to grow more. And, as Dr Panwar puts it, in previous years too sugar mills have delayed operations—as longer the cane remains in the field, higher the sucrose content and sugar yield.

The issue of cane price has been persisting for over three decades, points out S. Mahendra Dev, chairman, Commission of Agriculture Costs and Pricing (CACP). Dev attributes the mismatch between farmers’ price expectations and the government’s suggested price to the lacunae in the compilation of agriculture costs data. “We cannot chase the market price. The MSP and now the F&RP for sugarcane is the long-term price for farmers covering their costs. So the sugar mills should not pay less than F&RP,” he states.

He admits that the F&RP mechanism has been introduced to put an end to the state-administered price, “which was distorting the prices for political reasons. During a glut, higher SAP can hurt mills and also farmers, as there will be no buyers.” That’s why it remains a political hot potato. Many people, including Rashtriya Lok Dal chief Ajit Singh, are now questioning how the F&RP was formulated “without any discussion with farmer groups, states or political parties”.

The only saving grace so far this year is that unlike in UP, the mills in other major cane-producing states like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh are paying farmers Rs 180-200 a quintal and started crushing operations by October, thus helping improve the overall supply position. Clearly, only a cohesive government policy can ensure self-sufficiency in both foodgrains and sugar. Or else, the farmers and also consumers will have to swallow the bitter pill and pay dearly for it.

Tags