Too Many People, Too Little Training

The Ladder Has Rungs Missing

The ‘demographic dividend’ is skewed: the gap in jobs and skills is looking scary.

- By 2020, UP, Bihar, MP will account for 40% increase in working population, but only 10% of increase in income.

- Labour force growth largest in rural areas; employment growth elsewhere.

- Skill shortages a big risk for India. Most future job opportunities in sectors where Indians have little expertise.

- 89% of working population has no vocational training

- AP, Karnataka, Maharashtra top labour prospects ranking; West Bengal, UP and Bihar near the bottom.

***

Sabharwal describes as a “tragedy” the mismatch between the much-touted “demographic dividend” and the actual jobs for trained workers. It is only compounded by the fact that jobs are being created in states other than those where most people live. Each of these puts paid to India’s dreams of a demographic dividend. We may be an increasingly youthful nation, but we also have a rising force of unemployed, under-employed, untrained, or incorrectly trained workers. Though people are clearly moving from farm to non-farm jobs, or rural to urban, unorganised to organised, and subsistence self-employment to wage employment, the question is, are they moving fast enough and are states trying to keep up with the changing population profile?

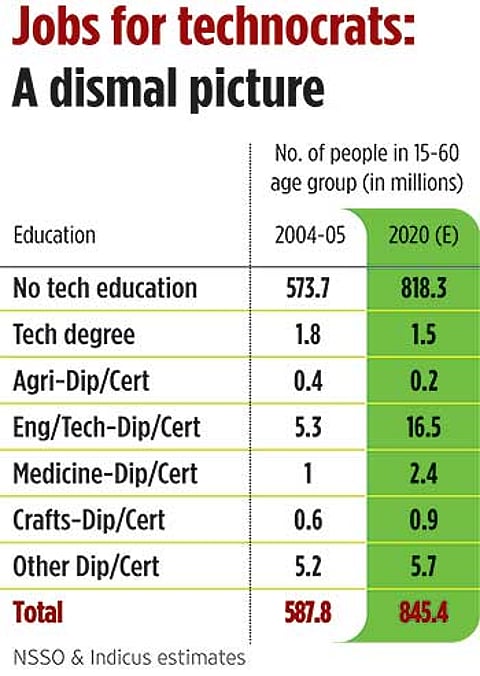

The skill-demand gap is neatly highlighted in ilr 2009: around 13 million new entrants join the workforce every year, but the existing formal vocational training capacity has been accessed by only 1.3 per cent of these—or less than 2 lakh people. Just vocational training will not do the trick either. Schools do lack vocational training, but at the same time “we must not vocationalise school education too much—the government cannot teach somebody in six months what they should have learnt in 16 years,” says Sabharwal.

A deeper look at the geographic mismatch (the previous ranking was in 2006) shows that in terms of the entire labour ecosystem—the demand and supply of jobs, and the implementation of labour laws—Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra are at the top. However, many states losing the opportunity to differentiate themselves are at the bottom of the ranking, and these have higher chances of housing more of the poor, witnessing forced migration and social problems such as Naxalism. “Demographics is not destiny and states can bend the curve with radical programmes to improve their employment, employability and education ecosystems,” avers Sabharwal.

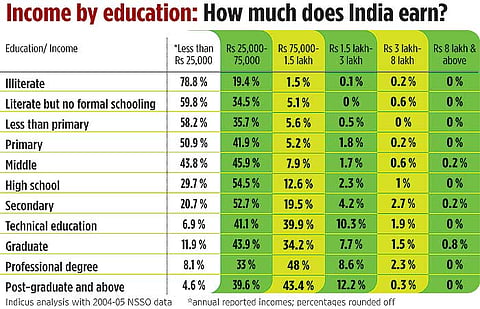

A substantial increase in capacity of vocational training, ways to enter and exit from the formal education system, and simple tools, such as allowing vocational training credits to be transferred as an “opening balance” to the formal education system, would work. But ensuring that labour gets trained in an employable, not defunct trade is also key. Besides unemployment, the “skill gap” has an unhealthy impact on livelihoods and the ability of Indians to climb out of poverty. The report finds that incomes naturally tend to rise with the higher number of years of education completed.

“At present, what we see on the ground is that subsistence self-employment is the most prevalent form of entrepreneurship in India, which needs to be replaced by decent wage employment,” Sabharwal says. Jobs will come, but not from where we think they will. Growth is going to happen but in industries, in places and environments where not enough Indians have been trained to work in. Unless the challenges, the youth demographic upsurge and the large-scale migration out of low-paying productive jobs, are managed well on all fronts—at home, in school, and in vocational centres as well as colleges and universities—the future looks scary.

Tags