***

Schizoid Cityscapes

Techies are rebooting urban equations. The cussed natives are revolting, the converts are rejoicing.

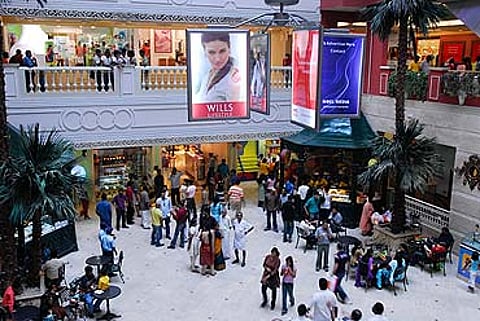

Today, in the southern cities, there is a clash of cultures—cool cats rub shoulders with their conservative counterparts, and career-capitalist segments are engaged in endless debates with the academic-ethical classes. In Bangalore, Koshy's (like Calcutta's Coffee House) coexists withNMH Tiffin Room. Chennai's IT hub on Old Mahabalipuram Road intersects with urban villages. And, in Hyderabad, says Khan, "Mumbai's Bandra-Kurla complex seems to have been grafted into Lucknow's old Imambara area."

Explains Solly Benjamin, an independent researcher: "Bangalore is, in many ways, a 'divided' city. The glass-walled office complexes, malls and entertainment centres contrast with the squatter settlements." Adds Mohammed Habeebuddin, a social worker in old Hyderabad: "Young girls here now complete education to work at a call centre. But many others don't give a hang about IT." Comments M.S.S. Pandian, an economist: "There is a huge gulf between the prosperous south and north Chennai. It's creating a condominium culture. It has made people in the north to seethe with anger."

To get a sense of this divide in physical terms, just take a look at the new socio-economic maps of Chennai that are being plotted by The Madras Office for Architects and Designers. They distinctly show that the modern clusters of atms and restaurants (serving international and Chinese cuisines) have cropped up in the southern part of the city. Says Pandian: "Unlike in south Chennai, one can hardly find anATM in north Chennai." Similar borders now define Bangalore.

But the more major changes are reflected in the daily lives of the city-dwellers. A theatre festival organiser, who recently moved from Pune to Bangalore, categorically says that she's "still seen as an outsider, even though we are allowed to work within the artistic community". She points out that when she was first called in to organise an important festival, "lots of people, very old and good friends, were really pissed off. I was shocked, but it is true. Cultural anxiety is economic anxiety with a mask on".

It is in Chennai, the last among the cyber-trio to change, that the tensions are more visible. Margaret Zinyu, a colour specialist with Ford Motor, talks about her experiences while looking for a house. "It was difficult to find one as most ads advertised for families, vegetarians, or Brahmins." Malavika P.C., an artist and graphic designer, recalls that her house search encountered several moralistic questions since "I moved out from my parent's home in Chennai itself". She concedes that the city is opening up, but maintains "it's still far, far more conservative than the other places I've seen".

Harpulak Bahadur, a senior manager with a leading KPO (knowledge process outsourcing) unit, agrees. "Even between Chennai and Bangalore, I think Chennai is still conservative in more ways than one. For instance, I still find it difficult to enter pubs in Chennai that do not allow stags. In Bangalore, I can easily offer to buy a drink to a girl outside any pub and enter it. That's how easy it is. In Chennai, I still struggle! But Chennai is also changing because of the outsiders," he explains.

Like in Mumbai, moral policing has caught on in the south. Nitya Raman (name changed), a local who works with a financial services firm, narrates her harrowing interaction with the cops. "Last month, I went to a friend's place after a few drinks at a pub, and his neighbours called the cops. They complained that my friend was running a brothel. Since my friends didn't understand Tamil, I intervened. I realised that I was a better 'enemy'—a local who didn't stand for any values. I was physically dragged to the police station, and spent four hours there. It was one long nightmare."

Although ad-filmmaker Mohammad Ali Baig says it is wrong for the non-IT sections to envy their counterparts in the Hitec City, he agrees that there is a cultural degradation. "Step into any BPO in Hyderabad, and it is difficult to tell one employee from the other. All of them look like copies of each other. Their aspirations are monetary, their dreams and body language the same. It is like a dead culture. The IT sector, while fulfilling monetary requirements, will only lead to a robot-like society," he feels.

Rues Ali Khan: "My generation of Nehruvian youngsters had different values about life, education, work and money. I know of youngsters in their twenties who have been put through a good education, but instead of pursuing a career like we would have, they are basically hustlers. They do a quick assignment or deal, make money, and hang around and 'chill' for a few months. Then they do it all over again. Logically, it makes sense: you earn well, you enjoy. But somehow it seems a flaky way of life to me."

Gnani, a noted columnist and writer in Chennai, agrees. "The trouble today is that we are seeing a breakdown of the feudal culture and the start of a capitalist one. In the old culture, a servant cared about the master as he was taken care of by the master. But there is no such personal relationship or emotional bonding in a capitalist culture," he says. "Sections of employees in new-age firms, who crave for pubs and an active nightlife, are already alienated from the society in some way. Unlike the '70s, the middle class no longer feels that it is the keeper of the society's conscience."

Benjamin explains the issue from an inequality perspective. "At present, almost one-third of Bangalore's population has only partial or no access to piped water. One study estimated that 'more than half' of Bangalore's population depends upon public fountains—many of which supply contaminated water." Access to other services like toilets is as bad. An official report stated that there were 1,13,000 houses without latrines, while 17,500 had dry latrines. In a study of 22 slums, nine had no latrines. In another 10, there were 19 public latrines for 16,850 households or 1,02,000 inhabitants.

Nonetheless, the techies think they have contributed to the socio-economic progress of the three cities. For example, those who defend the name Bangalore contend that they were partially responsible for putting the city on the global map, and for Bangalore to become a commonly used verb. Today, India is respected and the expatriate population has risen manifold because the lifestyles in these cities are comparable to any other western city. It was because of the IT revolution that Wired ranked Bangalore at a high 11th among 46 global technology hubs based on various parameters.

Ironically, the most vociferous support for the new culture comes from Chennai. Says Geetha Doctor, a freelance journalist: "I think Chennai's come a long way, and adapted very well. It's growing in a quiet but determined way. It's becoming hip and happening, and the profile is much younger. They have cleared up the IT highway, cleaning up and making the city more beautiful, and people have a civic pride that was never there before. We're, of late, witnessing a sort of Singaporisation of Chennai."

Adds V.R. Devika, an educationist and art critic, who works with anNGO and Prakriti Foundation: "Madras is mostly portrayed as a Brahmin city—it's not! There are many young people wanting to become the Jeans Generation, to become middle class and take the IT opportunity. Evidently, Madras is on the brink of major change. Despite its orthodoxy, it's very open—though in danger of becoming Bangalore. What's to be admired is that we are capable of jeans on the outside, davani (half-saree) at home." And, with no trace of ambivalence.

Tags