On The Flying Dodo’s Trail

Praful Patel is certainly not ‘Air India’s minister’, considering the sordid mess the national airline is in

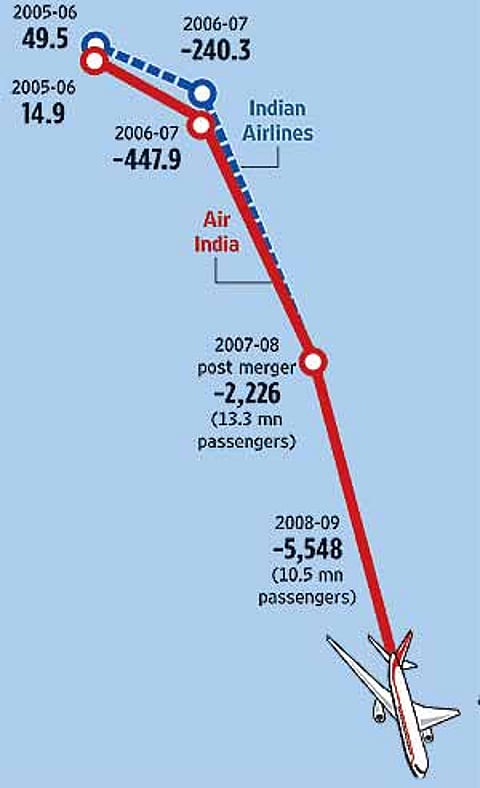

AI’s fortunes have taken a nosedive in the past six years

- Micro-management: Minister Praful Patel micro-manages the airline; management decisions emanate from his ministry HQ. Has strained relations with CMD Arvind Jadhav, who has a mind of his own.

- Morale: Professionalism takes backseat, top management unable or unwilling to read the changing market conditions. AI’s 11 MDs in the past 20 years had an average tenure of a year—with two exceptions.

- Merger: The 2007 merger between A-I and IA is widely slammed. AI still has an average of two managers per position, staff strength is three times what’s required, and it has a non-integrated fleet.

- Bilaterals: Massive additional air traffic rights granted to foreign carriers after 2004-05. But merged AI/IA is not in a position to increase capacity, leading to a fatal loss of marketshare.

- Withdrawal: For an airline that cried about having to service “unprofitable routes” for social sector responsibilities, A-I/IA inexplicably withdrew from profitable routes.

- Unions: Multiple unions—12 recognised, 20 unrecognised— have treated the paying passenger as a pawn in their larger game, holding airline operations to ransom.

***

The answers are not blowing in the wind; they lie in the seemingly disparate developments /decisions of the past few years which, airline insiders say, have systematically steered Air India towards chaos and collapse. “There’s no doubt AI has been heading towards an era of uncertainty; it’s being allowed to die,” says Jitender Bhargava, recently retired AI executive director. “But it’s not yet a lost cause.”

In a year that saw many international airlines succumb to the recession, AI cmd Arvind Jadhav managed to bring down operating losses. But then, it was also the year in which the government had to infuse Rs 2,000 crore into the airline. The moot point is not whether Jadhav, or his newly appointed coo Gustav Baldauf, can right the fundamental wrongs of the past years, but whether they have the mandate from Union civil aviation minister Praful Patel to do so.

Industry analysts trace the beginning of AI’s rot to the mid-90s, when a succession of airline cmds refused to recognise and adapt to the changing market conditions (the few who did were unceremoniously stymied). Authority and power had “decisively moved from Mumbai headquarters to the ministry in New Delhi by that time” is how an airline source puts it, with AI cutting down routes, withdrawing from gateways, dressing up its balance sheets and so on. But the unkindest cut came during Patel’s tenure in the upa-I government. Sources say that cmds V. Thulasidas (2003-08) and Raghu Menon (2008-09) either followed the minister’s agenda or preferred to take the backseat as key decisions were made in Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan in Delhi.

- Bleeding at Rs 300 cr a month

- Working capital loans above Rs 15,000 cr

- Needs about Rs 10,000 cr govt infusion to avoid sinking under debt

“Since 2004, Praful Patel has acted as the de facto ceo of the company,” says a well-placed source. “Day-to-day operations, bilateral negotiations and aircraft acquisitions were all done by the MoCA...the AI board became a rubber-stamp.” AI’s staffing pattern helped: key personnel appointed across departments with the ministry’s concurrence meant that the latter’s agenda met with the least resistance. Several decisions taken during this time need to be put under the scanner, sources say, but two of them are begging to be microscopically examined—the merger and subsequent “non-integration” of AI with the erstwhile Indian Airlines and the generous granting away of bilateral routes in a manner that openly hurt AI.

The merger to form National Aviation Company of India Ltd (nacil) was announced in August ’07, but AI sources aver that basic prerequisites were not followed. Among them: the integration concept was not discussed with employee associations though it involved merging “a vertical reporting line of AI with the regional reporting patterns of IA” which has led to duplication of officers in many posts. Then, revenue and reservation systems were not integrated leading to a duplication of airport counters and ticketing systems; a comprehensive vrs was not enforced causing gross over-staffing (staff strength is thrice that required). All put together, the ill-conceived merger drained AI—it’s bleeding a whopping Rs 300 crore a month.

The merger came in for much criticism this April from a parliamentary standing committee chaired by the cpi(m)’s Sitaram Yechury. “The decision to merge the two national carriers was taken in haste, without required consultation and homework,” it stated, adding that it had “given rise to many problems concerning financial, administrative and operational...two major objectives of the merger, ‘economies of scale’ and ‘increased leverage’ couldn’t be achieved”. Earlier, in March, the committee on public undertakings (CoPU) had similarly slammed the merger. The Yechury panel has proposed de-merging the airlines under nacil, which will function as a holding company.

The charitable view is that Patel rushed through the merger to bring in economies of scale and increase market shares, but there’s another view too—which points to an ulterior motive to benefit the emerging private airlines. “India’s agreements with other countries have designated two national carriers, AI and IA, to operate services abroad. This effectively prevented other airlines from international operations. The AI/IA integration obviated this problem, facilitating Jet Airways and later Kingfisher to launch overseas operations,” sources point out.

The other major cause of AI’s woes appears to be the spate of bilateral negotiations it was rushed into during the past 5-6 years. The CoPU report also raised a most central question: how was the merged airline supposed to make money if it ceded routes? “Air traffic rights are like the country’s natural resources; they are not negotiated unless national carriers can mount capacity to utilise their share of the rights. AI’s inability or limitations were not considered while negotiating the bilaterals,” says an airline source.

For instance, negotiations with Cathay Pacific meant it increased its Hong Kong-Mumbai flights from four to 10 a week, and Hong Kong-Delhi from seven to 14 a week, in addition to four new weekly flights to Chennai and a new point of call granted to its subsidiary, Dragon Air, to Bangalore with seven weekly flights. “Cathay utilised the additional rights almost immediately; AI has been unable to mount any additional capacity,” says airline insiders, adding that the granting of bilaterals was a “bonanza” that defies rational explanation.

So, what’s the deal? Somewhere in this systematic and deliberate grounding of the airline lies the key to its future. “Sometimes I wonder if there is a genuine desire to get AI out of the mess,” says Capt D.S. Mathur, a former cmd of the airline in the mid-90s. Adds a union leader, “The airline is being finished off so that private and/or international carriers can come in. That’s why some of us organised the Save Air India convention recently.” The unions have a vested interest in maintaining status quo in AI; where else will they be allowed to flex muscles, after all. Yet, he has a point that’s validated by others without any such interest. Like ad guru Alyque Padamsee, who says: “AI used to be among the top five, now it’s like a ghoda-gaadi airline. Long ago, I used to be proud to write ads for it, now I get scornful looks when I mention AI...it’s been destroyed by the mismanagement.”

Patel dismissed any suggestion of strategic sale to private players as “pure speculation” because it involved disinvestment decisions at the pmo level and any such was not in the offing. His critics—and there are many now—point to the ambivalent posturing of the minister. “Patel is on record saying that in his personal opinion most national carriers across the world have not done well and that some day the government may take a decision on AI ownership. If he was anti-privatisation, why did he sound pro-privatisation?” asks a senior airline official. Strategic alliances with private companies are still a possibility, say sources, but this will call for amendments in the Act.

As pundits, aided by a section of the media, drum up the privatisation fervour, a few voices are talking about operational independence. Those like Bhargava and senior officers argue for a de-yoking of AI from the ministry and allowing the cmd and/or coo to “run it as a professional organisation in a professional environment”. Yechury called upon the government “to write off the losses and then think of giving it a fresh direction, considering that the huge losses are because of the irrational decisions of the government”. Airline sources say a turnaround will mean a fresh dose of funds from the government, which in turn implies greater control and authority, not less.

Though Praful Patel has remarked that he “is civil aviation minister, not Air India’s minister”, it’s unlikely that he will let go of the levers anytime soon. Many wonder why he was promoted to cabinet rank in upa-II when he should have been facing inquiries for “malfeasance and malintent” in taking decisions that systematically undermined the national carrier and jeopardised its future. Not everyone in Air India building is convinced that he intends to put AI on the recovery track.

Tags