Inclined Planes

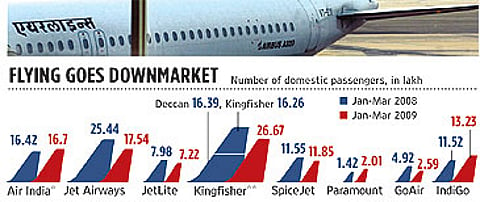

Low cost airlines take off with a roar

Source: Ministry of Civil Aviation

Sure, the cost differential between a full service and an "efficient" LCC continues to be around 30 per cent, say aviation experts. But with higher aircraft utilisation, lower personnel, sales, marketing and administrative costs, LCCs have an edge over full-service players. As the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (CAPA) says in a recent report, given that LCCs are largely debt-free, they could turn around if fuel costs remain below $50 a barrel. Ominously, the report highlights that it does not see a market for full-service airlines beyond the six metros.

Generalisations are meaningless in the current economic environment, counters Saroj Datta, Jet Airways' executive director. "Yes, the market is predominantly looking for lower fares. But is that going to be the case two years from now? It definitely wasn't so five years back," he says. Datta refuses to comment on why the troubled airline needs two low-cost options (it already has JetLite, formerly Sahara). But it's obvious that the regulatory and legal hangover from Jet's acquisition of Sahara is proving to be a drag.

Either way, the unhappy environment has compelled Jet and Kingfisher to explore an alliance, and now they're looking at lower fares. It remains to be seen if these two airlines can operate a low-cost service at full operational costs. Even though airlines have been cutting personnel costs and trimming capacity over the last few months, there are significant accumulated losses and huge debt burdens they have to deal with.

Is low-cost the way forward then? It's tough to say—it's not that the LCCs themselves are in the pink of health. A lot depends on the economy. It's safe to assume the low-cost challenge looks good for now. It's also clear that there's not enough room for so many players. "Consolidation has to happen. By their own admission, LCCs cannot operate by competing with each other," says Kapil Kaul, CEO, South Asia, CAPA. Clearly, low-cost is where all the action is going to be.

Tags