Bonsai Netbooks

India announces the cheapest computer amid doubts over sustainability

- 11 litres of enhanced petrol in Bangalore: Rs 543.40

- Casio FX-991M scientific calculator: Rs 790

- 10 shares of Satyam Computer (on Feb 4): Rs 501

- A PVR gold ticket at Select City Walk, Delhi: Rs 550

- Bombay-Delhi non-AC sleeper ticket (Tatkal): Rs 575

- Domino’s pizza (Non-veg): Rs 529 (taxes included)

- CAT exam application form (reserved category): Rs 650

***

That's all we know for now. The HRD ministry has been rather secretive. According to reports, the project was being developed with help from the Vellore Institute of Technology, IISC, Bangalore, iit Madras and a few PSUs. However, IIT Madras director M.S. Ananth and Ashok Jhunjhunwala, a pioneer in low-cost computing devices, told Outlook they were not involved in the project. Even senior officials at IISC claimed they were not involved in project Sakshat.

While the exact details remain unclear, the government insists Sakshat will mark India's march into the world of computer manufacturing at an unbelievable price point. Really? Forget for a moment the sarcasm over whether India could really introduce a product that could define a new paradigm in low-cost computing. After all, Indian manufacturing has thrown up the Tata Group's low-cost car Nano (which has been delayed no doubt, but has captured the world's imagination).

The bigger doubt is whether India's fascination with low-cost computing devices will yield a winner. They've been around in various hues, shapes and brands, some even with blessings from the government. But most sank without a trace against competition from established multinationals that played with price and features to draw customers closer to fully-functional models.

In 1991, the government had come up with a computer priced at Rs 10,000 but could not sustain it. In 1999, the hand-held Simputer made headlines but is yet to gain critical mass. NetPC, a stripped-down internet access computer promoted by Chennai-based Novatium, had limited success. Other products like HCL's Compact MyLeap laptops fall roughly in the same category—but are priced much higher, at around Rs 13,000.

To be sure, affordability—and the greater goal of spreading computing to a wider audience—is a worthwhile target. The government plans to distribute its latest offering to educational institutions in rural areas. The project is part of the Rs 4,612-crore National Mission on Education through ICT. Already, there's confusion over the price. The initial tag was Rs 1,000 but the government plans to bring it down depending on the volume of orders. But sources say the actual price would be between Rs 1,000-1,500.

Make no mistake, that's an achievement. Either way, Sakshat would be the cheapest computer in the world, if one can call it that, far cheaper than the XO laptop developed by MIT Media Labs founder Nicholas Negroponte's One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project, which planned to distribute $100 (Rs 5,000) laptops for education. Currently, OLPC's XO laptop costs around double the amount, at $180-200 (around Rs 10,000).

But even at that level, is there a market in India for such stripped-down machines? The government believes only low-cost devices could change India's poor PC penetration levels which stands at 3.6 per cent. The real picture is, however, different. Says Girish Mehta, director, consumer marketing, Dell: "People who are buying their first PC tend to go for a fully-functional device. They are normally looking at a machine that is able to take on new applications even two years later." And that holds good for most rural areas as well. A lot of companies are also donating fully-loaded PCs to schools in remote areas. Adds Nasscom president Som Mittal: "India needs a low-cost computing device. But where taxes add 20-22 per cent on the price, even low-cost machines become expensive."

Analysts feel Sakshat wants to take on OLPC, which was initially shunned by the ministries but later supported by the PMO and finally launched in India last September. Says OLPC India president and CEO Satish Jha: "We have met a large number of people in India and every single education secretary we met has liked the idea." But will the Rs 500-computer be able to take XO head on? As expected, analysts have been scathing.

The viability of pricing the product cheap was a key point of attack. Most experts felt that, at Rs 500, it would be difficult to have even one key component of the machine. Not surprisingly, OLPC—which would be most affected if Sakshat succeeds—is not convinced about the workability of the idea. Says Jha: "It will be interesting to see how this device is put together because the chip for a laptop is not available for less than $18, while the plastic casing, wiring and parts add another $20. With raw materials, factory wages and labour, it's impossible to come up with a product at that price. We created a world where the cost of a laptop was brought down from $1,000 to $100. But to have the product at $10 seems strange."

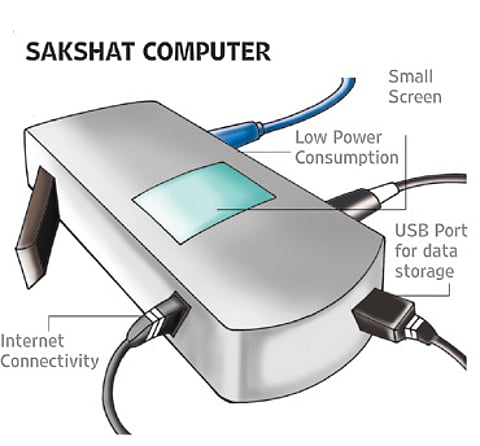

According to sources, the only way the laptop could be produced so cheap was by using a small screen and keyboard in a thin, low-cost plastic casing and run by a low-power processor. The product most likely would not have a CD/DVD drive or a hard disk—it would have internet access as its main function with a capability to store data only on external devices like portable hard drives or flash cards which could cost more than the machine itself.

Observers feel that with the general elections in sight, the government may want to strike the right note with the rural public by promising the world's cheapest computing device. But as of now, nothing concrete is available and no one seems to have used and tested its capability. According to an official connected with the development, even what was showcased at Tirupati last week was a "pre-prototype or a concept model" to show the government's intentions rather than final shape of the product itself.

Having created such hype, the onus is on the government to deliver. The world is already calling it a damp squib. Will the government—and the agencies apparently associated with it—be able to prove it otherwise?

Tags