Dhobi Ghat (2011), written and directed by Kiran Rao, reimagined Mumbai through intersecting lives shaped by art, class and longing.

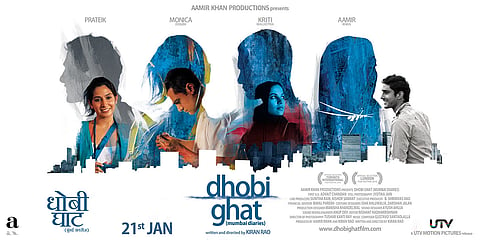

Starring Aamir Khan, Prateik Babbar, Monica Dogra and Kriti Malhotra, the film blended realism with quiet, intimate storytelling.

As Dhobi Ghat completes 15 years today, it stands as a gentle, enduring tribute to Mumbai’s unseen emotional landscapes.

Mumbai As Witness: ‘Dhobi Ghat’ And The Many Distances Of The Maximum City

‘Dhobi Ghat’ mirrors the rhythm of the city itself, where lives intersect, diverge and move on, leaving only fragments of intimacy behind.

Mumbai is not one city, but many cities within one big city, and in Hindi cinema it has rarely been content as a backdrop. It asserts itself as a character, sometimes even the most enduring one, in stories about its people. The most recent cinematic memory many of us carry of this city is All We Imagine As Light (2024), Payal Kapadia’s Cannes-winning film that tenderly captures Mumbai as a place that somehow holds space for everyone, from everywhere. Its gaze is gentle, patient, and deeply attentive to the rhythms of everyday life in the city.

But stepping a little further back in time, there is another film that continues to offer that same quiet enchantment. Kiran Rao’s Dhobi Ghat (2010), released fifteen years ago today, marking her directorial debut, remains one of the most evocative portraits of Mumbai in contemporary Hindi cinema. Both films open in strikingly similar ways, offering the audience a fleeting view of the city from inside a moving car. It is an invitation rather than a declaration—a window-peek before the plunge. From that moment on, we are immersed in the city by the sea, not as a spectacle, but as lived experience. A rare blend of art and commercial cinema, Dhobi Ghat was a pathbreaker in its time, quietly trailblazing a way of seeing Mumbai that continues to resonate.

Dhobi Ghat follows four individuals who inhabit vastly different social and spatial realities within the city: Arun (Aamir Khan), a reclusive painter averse to explaining his work, even at his own exhibition; Shai (Monica Dogra), an NRI investment banking consultant on a sabbatical, pursuing her hobby of photography while in the city; Munna (Pratiek Babbar), a dhobi from Bihar who dreams of becoming an actor; and Yasmin (Kriti Malhotra), whose presence in the film exists only through videotapes, her life mediated through recorded memory. The film threads these lives together with quiet precision, allowing their connections to be felt before they are fully noticed. Even fifteen years later, the seamlessness holds, avoiding tidy convergences and letting the city do what it always does: drawing people close and then letting them slip away.

From its very first images, Dhobi Ghat defines Mumbai through labour rather than spectacle. The opening credits linger on construction workers at a building site as dawn breaks, their bodies already in motion as the city wakes up around them. This is a Mumbai built through repetition and routine. Later, during his exhibition, Arun dedicates his work Building to the people who “build the city” and continue to search for a sense of belonging within it. Yet, the film quietly unsettles this gesture. The question of who belongs to the city, or who is allowed to belong more, is deeply shaped by privilege. For those who spend their days constructing the city and their nights struggling to survive within it, belonging is not an abstract idea to be contemplated. Survival leaves little room for reflection.

This imbalance becomes clearest in the film’s quieter moments. When it rains, Arun casually holds his glass out, letting the rainwater mix with his drink before taking a sip. The rain becomes a fleeting sensation, almost a private indulgence. For Munna, the same rain demands a different response. In his chawl, he places a mug beneath the leaking roof, turning weather into something that must be managed rather than observed. Arun can withdraw, protected by class and art. Munna, meanwhile, has to struggle just to get through the night. Through these contrasts, Dhobi Ghat reveals how the city offers vastly different forms of shelter, movement, and visibility to those who inhabit it.

Across the film, the city’s lifeline is sustained by forms of labour that are usually pushed to the margins of the cinematic frame. Clothes are washed, rooms are cleaned, walls are painted, meals are cooked and buildings are erected. Munna’s work at the dhobi ghat and the constant background presence of workers moving through the city form the texture of everyday life. Yasmin’s videotaped observations include a brief moment where her gaze settles on the maid across the building, a small but telling glimpse into the everyday systems that keep the city running. These moments underline how closely labour and intimacy coexist in the city, even when divided by distance and class. By foregrounding this labour rather than aspiration montages or skyline shots, Dhobi Ghat quietly resists the familiar cinematic grammar of Mumbai as a city of arrival and upward mobility.

This understanding of Mumbai comes into sharp focus when Munna shows Shai around the city in exchange for helping her build a photography portfolio. When Shai says she wants to see the city and its places, Munna responds with a laugh, asking if she really wants to see its filthy places. The moment is brief, almost throwaway, but it exposes a sharp divide in how the city is imagined. For Shai, the city is something to be explored, framed and archived. For Munna, it is something endured, navigated and worked through daily. The “filth” he refers to is not merely physical, but tied to the invisibility and precarity that underpin the city’s functioning.

If labour gives Mumbai its visible structure in Dhobi Ghat, memory and recording shape its inner life. The film is as much about recording as it is about living. Yasmin’s videotapes, Arun’s paintings, and Shai’s photographs are not just artistic expressions; they are attempts to hold on to moments. Each character reaches for a different medium, and with it, a different way of being seen. The city becomes both subject and storage, an archive that absorbs these gestures without ever fully responding to them.

Yasmin’s tapes are the most direct form of address. She speaks to the camera as if it were a confidant, a stand-in for the intimacy missing from her everyday life. Arun’s paintings, by contrast, resist explanation, even as they insist on observation. Shai’s photographs sit somewhere in between, capturing surfaces, movements, and fleeting encounters, aware of their own distance from the lives they frame. Together, these modes of recording reveal a deeper question the film keeps returning to—who gets to document Mumbai, and whose lives survive only in fragments, partial traces, or second-hand records.

There is also something more intimate at stake here. At its core, Dhobi Ghat understands that love is often a desire to be witnessed—to be seen, remembered, and held in someone else’s gaze. For many, especially those who arrive in the city carrying hope and longing, Mumbai itself becomes entangled with that desire. Love begins to feel synonymous with the city. Being witnessed by Mumbai and its people comes to resemble a form of validation, a way of proving one’s existence within it.

Yet Mumbai, as the film repeatedly shows, is structurally incapable of offering that kind of reciprocity. Its scale, pace, and indifference make sustained witnessing almost impossible. People brush past one another, lives intersect briefly and then disappear. Yasmin’s videotapes are meant for her brother, yet they also carry a fragile desire for connection, a reaching-out in the hope that someone, someday, will watch. Munna dreams of being seen, but is constantly deferred. Arun observes without fully committing and Shai frames the city without ever belonging to it. What the city offers in return is partial: a witnessing that arrives in fragments, never as completion.

What Dhobi Ghat captures, with remarkable clarity, is how people spend entire lives negotiating this gap. The longing to be seen and the reality of being overlooked coexist without resolution. There is no grand melancholy here, no romantic promise of fulfilment. Instead, the film approaches this pursuit with a quiet, almost cynical realism. It acknowledges that the desire for witnessing, whether through love, art, or the city itself, often remains unmet. And yet, people keep recording, looking, and reaching out, hoping that something, or someone, will notice.

By the time Dhobi Ghat reaches its final moments, there is no sense of closure, only realization. Everyone understands something essential about class, distance, and desire, but too late for it to alter the course of their lives. What lingers is not catharsis, but an acceptance of disconnection. Mumbai continues. The characters do not win or lose; they simply learn how to see. Connection exists, but only as fragments. The film offers repeated gestures that resemble intimacy: Arun watching Yasmin’s tapes, Shai photographing Munna, Munna lingering around Shai with hope and longing. But these connections are never reciprocal. They move in one direction. Observation is mistaken for intimacy, and attention for attachment.

Each character, in their own way, comes to terms with this. Arun realises that his absorption in Yasmin’s life does not grant him access to her truth. Shai begins to see that her closeness to Munna was always shaped by her mobility, by the certainty that she could leave. Munna, perhaps most painfully, grasps that visibility does not guarantee belonging, that being seen does not mean being chosen. The tragedy here is not loneliness itself, but the brief illusion that these distances could be crossed.

And this resonates beyond the film. It is the truth of real Mumbai as well. The acceptance of disconnection is the recognition that the city allows people to brush past each other endlessly, without ever crossing the same existential plane. Whether in chawls, trains, offices, or streets, the city’s scale, pace, and structural inequalities make deep connections rare. People share space, glance at each other, sometimes even touch lives, but rarely meet on the same emotional or existential plane. Dhobi Ghat captures this with an unflinching realism. Its quiet observation mirrors the rhythm of the city itself, where lives intersect, diverge, and move on, leaving only fragments of intimacy behind.

In the end, the film asks us to notice those fragments, to witness them without demanding resolution. And perhaps that is Mumbai’s most essential lesson: that connection exists, fleeting and partial, often at a distance, and learning to see it, and to live with its limits, is a kind of understanding in itself.