Hrishikesh Mukherjee died at the age of 83 on August 27, 2006.

His cinema was sensitive and political, steeped in the inherent goodness of people.

Humour in his films was a narrative tool to propel socio-political consciousness.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee Death Anniversary | The Man Who Made Cinema With A Heart

Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s films often feel like returning home—films filled with a belief that people are inherently good and want the good. They are seemingly simple, yet poignant, deep, political and soft.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s cinema was steeped in the inherent goodness of people—in looking beyond oneself, in kindness, and in the desire for an equitable world. His gaze was deeply sensitive, and political, which reflected in the writing, dialogue, topic and picturisation of his films. Often set within the familial structure, his cinema offered a peek into interpersonal relationships, raw emotions, prejudices and idiosyncrasies with a lot of laughter and smiles.

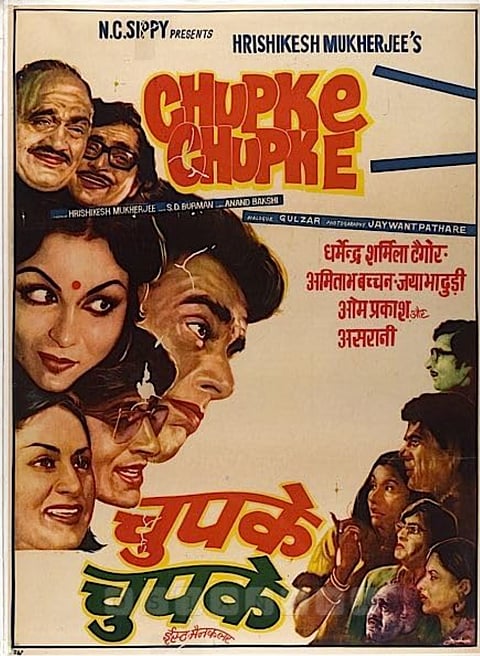

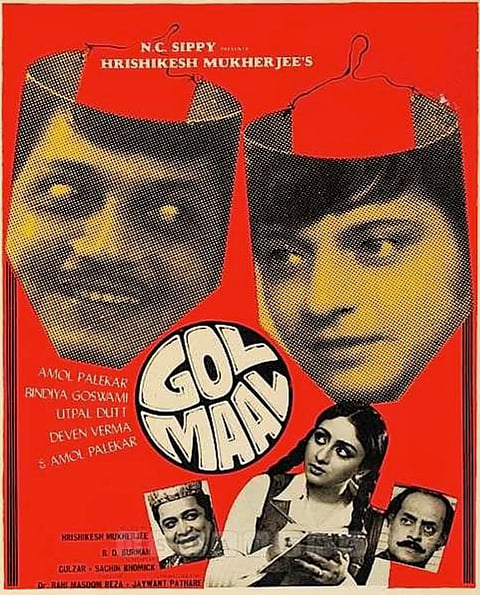

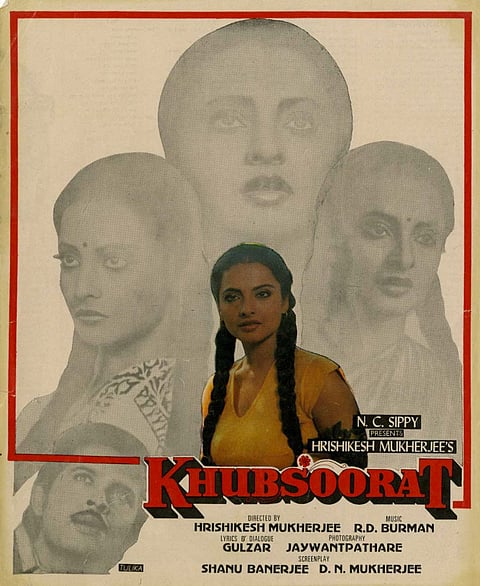

Humour in Mukherjee’s films was not slapstick or a foil to serious conversations, but a tool and a narrative in itself that propelled socio-political thinking, conversations, detailing and the subtexts of films. The comedies were unmistakably sharp in nature, persistently asking questions around social issues such as unemployment, as in Golmaal (1979); class, privilege and the entwining of language superiority, as in Chupke Chupke (1975); innocence, infatuation and the fickle fame in a fabricated world, as in Guddi (1971); and inclusivity, hunger and the need for respect in Bawarchi (1972). It was an art that is woefully lost today, as contemporary cinema relies either on sexism and objectification of women for humour, or juvenile narratives and bizarre tropes to induce momentary laughs, devoid of meaning and a point of view.

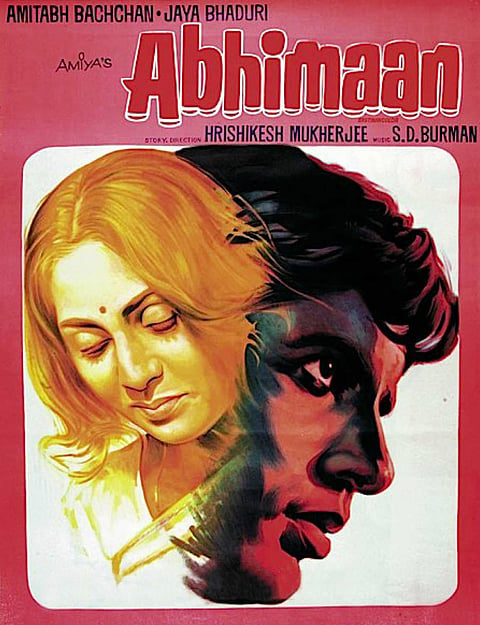

However, to bracket Mukherjee’s cinema only as a comedy genre would be a colossal disservice. Some of his finest films, like Satyakam (1969), Anand (1971), Abhimaan (1973), Mili (1975), Alaap (1977) are not comedies, but carry the proverbial Hrishikesh Mukherjee stamp of seeing the world not as it is, but as it should be.

Themes of class difference, politics of language, intention of work—servitude vs capitalistic dreams, gender dynamics and commentaries on power have all been at the heart of Hrishi Da’s (as he was lovingly called) films. And what is most interesting is, despite the films being comedies or dramas, the themes sometimes emerge stronger than the narrative styles. Certain scenes, dialogues, characters have lived on in public memory as testimonies to these themes and are reminders of the power of the writing in these films. His writers included the likes of Gulzar, Rahi Masoom Raza, Sachin Bhowmick, DN Mukherjee and many more.

Some of the most immortal parts of Hrishi Da’s cinema are the dialogues that convey so much more than just a few words strung together in conversation. When Anand meets Bhaskar for the first time in Anand, he says, “Babumoshai, zindagi badi honi chahiye, lambi nahin,” a memorable line penned by Gulzar. In Golmaal (1979), Rahi Masoom Raza breathed life into the quirky film with his writing, in lines such as “Isiliye pitaji kaha karte the ki lambe kapde pehenna bahot haanikaarak fashion hai. Fashion ke woh viruddh the,” said by Ram Prasad Dashrath Parsad Sharma to Bhawani Shankar, as he explained the mathematics that justified his mini kurta. Such gems are sprinkled all over his films that make them absolutely unforgettable.

His films such as Anand, Guddi, Bawarchi and Chupke Chupke spoke vociferously of class disparities. Dr Bhaskar Banerjee’s (Amitabh Bachchan) frustration and helplessness are palpable in Anand, as he works through the slums of Mumbai, where he goes to fight diseases but has to fight poverty, lack of hygiene and lack of education instead. He neither has the means nor the preparedness to tackle these challenges. The films talks of what the class difference does to the idea of health—where the rich fabricate issues for attention and pay for them, and the underprivileged suffer with actual illnesses since they can’t pay for treatments. In a particularly poignant scene between Bhaskar and Prakash (Ramesh Deo), they talk to each other about what the practice of medicine entails, whether it is capitalistic or not, whether it is morally sound for it to be capitalistic. Prakash responds explaining how he makes money off the rich to enable the underprivileged to take treatment free of cost. These are significant debates to have, and are possible on screen purely because both the writers and director view the world through the perspective of the have-nots.

In Guddi, Dharmendra (as Dharmendra) admonishing the photographer pursuing him for an interview and photos, despite a labourer collapsing on the same set, is another testimony to the same gaze. The conversation in the scene critiques the bourgeoise press and the machine that needs to make money. It highlights how education degrees possibly don’t pay, but hobbies sometimes enable sustenance. In a beautiful meta scene just before this, Dharmendra looks at the burnt stage of a studio referring to the fickle realities of cinema and fame, and how everything eventually crumbles to dust—with the light faced upwards on the ground as a beautiful metaphor. In both the films, the commentary on class is in strikingly different moods with different layers, but is just as deep and critical.

Bawarchi presents the idea of knowledge as deeply entwined with class. The incredulity and skepticism in the family members with respect to Raghu’s (Rajesh Khanna) knowledge as a bawarchi is testimony. However, through the course of the film, this gives way to genuine respect and understanding. Similarly, Chupke Chupke looks at the absurdities of the English language through the feigned innocence of Pyaaremohan (Dharmendra), a driver. The fact that English will be understood with all its complications by the employers and Hindi (and Urdu) with their pride, beauty, detail and vocabulary by the employed, is a soft rap on the knuckles of class privilege. All these films insist that we respect people within the divides, beyond our own prejudices of them.

His politics also permeated the dialogue-writing in these works—whether it is Golmaal, where one of the friends in the circle says to the rest, “Emergency hatt jaane ka yeh matlab nahin ki aap log jab chahe manmaani karein, shor machayein”; or Chupke Chupke, in which Sulekha, when branded as a communist for asking her friends to carry their own bags instead of asking the chowkidar to do so, says, “Iss mein communism ki kya baat hai?”; or Guddi, where Navin (Samit Bhanja) writes in his diary, “Kitna bada farkh hai, ek hi film se ek laakhon kamaata hai, aur doosra phaankon par guzaara karta hai. Yahi farkh hi shayad sabsa bada rog hai is industry ka. Lekin is industry ka hi kyun, kya yahi farkh humaare saare desh ka rog nahin hai?” These are just a few examples of the succinct lines that insist we confront the disparities in the society around us.

The gender lens is also critical in Mukherjee’s films. The women protagonists have agency, are free spirited, vociferous and not shy to put their points across. There is Guddi (Jaya Bhaduri), who refuses to marry because she believes she is in love with Dharmendra; Sulekha (Sharmila Tagore), who defends her apparent closeness with Pyaaremohan; Uma (Jaya Bhaduri), who leaves her home after being disrespected by her husband, clearly jealous of her success and broken by his failures; Urmila (Bindiya Goswami), who refuses to marry as per her father’s wishes and gives an ultimatum both to him and her boyfriend; and Mili (Jaya Bhaduri) who isn’t afraid to confront anyone for what she believes is right. Each of these women has a voice that they use fearlessly. The most refreshing aspect was how Hrishi Da developed characters like Runa (Aruna Irani) and Chitra (Bindu) who, in any other film, could’ve been slotted in the patriarchal gaze as the vamps—but here were women in control of their narratives, agency, body, power and authority, which was an incredibly powerful feminist stance in the 1970s. The male characters in his films also came across as allies, not toxically male, but supportive, gentle men, unafraid to be vulnerable.

Many times in the lists of Bachchan’s films on the “angry young man”, three critical films get eclipsed. These belong to Hrishikesh Mukherjee, in which Bachchan’s characters are very angry and disillusioned—in some cases, with the systems or the lack of them; in other cases, in their own personal lives, having believed patriarchal narratives which are not their lived experiences; or sometimes, owing to social ostracism that stems from prejudice. These three films are Anand (1971), Abhimaan (1973) and Mili (1975) respectively. In each of these films, varied layers of men’s vulnerabilities have been exposed. There is also anger—utilised against systems, internalised due to customs and then broken away from, and detached due to final acceptance. These films are critical films in Amitabh Bachchan’s filmography as well, since they add many more dimensions to his portrayals of masculinity and of the angry young man himself.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s films often feel like returning home—films filled with a belief that people are inherently good and want the good. They are seemingly simple, yet poignant, deep, political and soft. Unthreatening, they make us think about everyday choices we made then, and continue to make each day. His work explores how we negotiate with power, what it means, how we use it, what stories we wish to tell and why, whose stories we tell. Unfortunately, the middle class is practically lost from storytelling in today’s cinema as is the simplicity. Hrishi Da’s films remind us of what was once said in Bawarchi— “It is so simple to be happy, but so difficult to be simple.”

Tags