Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar (2025) released on 5 December, was largely applauded for its performances.

Critics who called out its nationalist pandering were subjected to harassment and intimidation.

This article examines how dissent is policed—and why critical engagement is becoming increasingly dangerous.

Critic Khatre Mein Hai: Inside Dhurandhar’s Selectively Manufactured Outrage

At a time when the country is choking on polluted air, unsafe water, a cost-of-living crisis, gendered violence, caste discrimination, and countless unresolved failures, it is stunning how the parameter of “love for the nation” is rerouted towards conveniently manufactured communal provocations.

There’s a certain self-absorption in treating every critique not merely as a personal attack—but as an attack on nationalism itself, whose own foundations are so fragile that its mouthpieces resort to vulgar profanities over mere opinions on a film. One wishes this fervour was directed towards the genuine betterment of the nation, towards holding the people in power accountable and challenging those who exploit the shallow reserves of media literacy and individual conscience. Yet, it would be unfair to assume that a country that gave us Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2013), Rang De Basanti (2006) or Veer-Zaara (2004) lacks the discernment to appreciate films that intellectually probe authority. Just a couple of weeks ago, Aditya Dhar’s highly anticipated spy-thriller Dhurandhar (2025) released in Indian theatres with a stellar cast and a promising story. The trailer revealed a grandiose saga of betrayal, gore and nationalism.

Yet its most persistent flaw, one that many critics have flagged, lies in its casual but consequential misuse of the phrase “fiction inspired by real events”. Much of the public outrage directed at critics rests on a basic misreading of intent: nobody disputed the tragedies themselves, only resisted the casual invention of (fictional) details filled in to engineer a preferred narrative. Many film critics like Anupama Chopra, Rahul Desai, Uday Bhatia, Tatsam Mukherjee, Anas Arif, along with the author of this article were met with disproportionate backlash for reviews that were less argued against than preemptively dismissed.

Chopra, a senior film critic (and chief editor) at The Hollywood Reporter India, whose video review of the film was taken down, prompted several questions on freedom of expression and protecting the voices of critics simply doing their job. Due to a clash of corporate interests in the parent company of both the publication and the film’s album being the same, along with the rampant harassment—it is speculated that the video review was hence taken down. The Film Critics Guild recently released a statement condemning the bullying and harassment against critics which many people stood by.

If a respected, influential critic like Chopra can be threatened by coordinated backlash, the moment demands harder questions: why has a single film triggered such collective hostility; and how do we safeguard voices of dissent? It is worth noticing how opinions that are most “visible”—whether YouTube video reviews or Instagram reels—invite disproportionate scrutiny, even more so when the voice belongs to a woman. Chopra, Sucharita Tyagi and Ishita Sengupta, for instance, were met not with counter-arguments but with sexist, misogynistic, and even rape threats. The commentary fixated more on trying to suppress them for simply having a voice more than for what they wrote, exposing the fragility of those behind the comments.

For the general audience, the critic’s role has become oddly elastic—to either encourage or discourage viewership of a film or to validate people’s personal opinions. The failure to do so results in them being labelled “dishonest”. This has also reached a point where a so-called “work of fiction” is enough to justify communal slurs against Muslim critics and casual branding of dissenters as “terrorists” and a steady stream of abuse escalating to even their families.

Reflecting on how journalists can be protected, Film critic B.H. Harsh says: “The changes need to begin on higher levels, where a press meet with political leaders is not shunned, where writers and media professionals are not constantly censored or compelled to self-censor. To start with, some ground rules need to be set (and followed sternly) about social media conduct, about how criticism can be confused with abuse under any circumstance. If we achieve that, I will regain some of my hope.”

The audience’s violent reactions towards critics mirror the film’s intent—it insists on being defended and championed in the face of dissent, extending fear not just to an imagined enemy across borders but to “hidden enemies” or fellow citizens who do not share the same religious and nationalist ideas as them. What is more telling is how critics are attacked for stating the obvious: films timed around elections are rarely accidental, and even less so in their intent to sway public sentiment.

When the previous Dhar film Uri’s chest-thumping “How’s the josh?” migrated seamlessly from the screen to political rally slogans, the film’s real-world function could hardly be mistaken. Article 370 (2024) went further, openly endorsing the ruling government’s revocation of Kashmir’s statehood, framing the move as an act of singular heroism that rescued the nation. B.H. Harsh also points out this absurd fixation with Pakistan: “Honestly, I wish this came purely from lack of imagination on storytellers’ part, but not the higher need/desire to pander to certain political figures or huge sections of its audience. It’s the lowest hanging fruit, a story about India-Pakistan, going on for almost 30 years.”

Film critic Ubais adds to the conversation: “Just because Kashmir has been associated with terrorism, or Pakistan is known for it, doesn't mean that most citizens, or even a celebrity from there, should be labelled as terrorists. But, our films often reinforce nationalistic ideologies, perpetuating the "us vs. them" mentality, where we consider ourselves superior in such narratives. I find it troubling when violence is glorified using verses from the Gita; I can't help but question how this differs from extremism.”

Incidentally, the practice of paying up those with mass reach has reshaped consumer behaviour and cinema has hardly been spared. Criticism and “reviewing” have steadily turned into a form of currency diluted by influencer culture, where a generous cheque can launder public perception through social media. Fund the influencers, activate the PR machinery and the narrative is marketed exactly as designed. Dissent, then, is no longer part of the dialogue but treated as a defect—an inconvenience to be managed. Anyone who disrupts this carefully curated consensus is sidelined, bullied under commercial pressure, or, in some cases, quietly made to delete their reviews like Chopra and others.

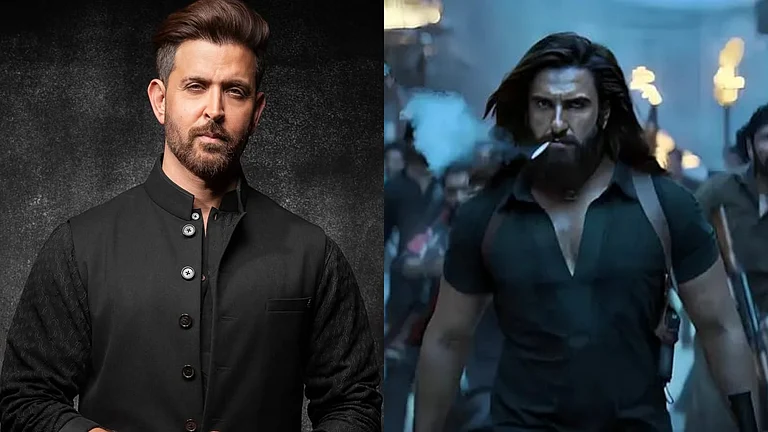

Social media too, is flooded with slick edits of actors from the film. In today’s digital ecosystem, virality is rarely a coincidence; often carefully orchestrated by filmmakers and digital platforms alike. Content seeding, in this context, becomes a subtle way to redirect mass engagement away from potential dissent. Flipperachi’s hit ‘Fa9la’ (pronounced Faasla) from Dhurandhar immediately dominating reels wasn’t accidental or completely organic, so weren’t the Akshaye Khanna and Ranveer Singh edits. The song (which surely, is catchy) first circulated through paid/promoted posts on major meme pages, and once it gained traction, smaller creators followed—turning it into a trend that sustained hype around the film.

Attention is the new currency—and it’s easily spent to steer public opinion. In this age of micro-managed narratives, genuine reactions are crowded out, replaced by constant cues quietly telling us how we’re supposed to feel about what we’re watching. In the larger scheme of things, this “distraction” doubles as a political tool, allowing a film that is loudly “pro-India” to keep the wider public comfortably removed from interrogating deeper structural issues.

Beyond social media, nearly every actor has, at some point, leaned on these very critics for defence. The industry abandoning them now and pretending otherwise is a case of selective amnesia. When established actors like Paresh Rawal and Yami Gautam hop onto the trolling bandwagon, it’s almost comical how a handful of nuanced reviews that dared not blindly applaud a film can trigger an entire targeted viral lynch mob. This influence not only plays on a certain power imbalance and attempt to maintain superiority over them, but also keeps them in check.

When Hrithik Roshan acknowledged the film’s competence while still calling out its propagandist undertones, the outrage didn’t follow him, but took a familiar, uglier detour—towards his Muslim partner, Saba Azad. She was cast as the convenient villain, accused of being a “bad influence,” even of posting that statement on his behalf. This orchestrated hate-machinery is a double-edged sword—one that polices dissent not only from those whose job it is to question, but also from those who are supposedly “one of them”.

Film critic Siddhant Adlakha elaborates: “Most of the critics receiving this sort of backlash are ultimately freelancers or self-employed, so they don’t have institutional protection. We are all part of a media ecosystem where journalism is increasingly at the mercy of private equity, which is itself increasingly in bed with government forces, whether it’s in India, the US or elsewhere. So this sort of problem runs deep, and the mass harassment of critics is just one ugly symptom”.

This is the power of hypernationalist filmmaking. It thrives by erasing the line between fact and fiction. This film, by stoking the idea “Hindu khatre mein hai”, freely borrows real audio and splices it with creative liberties, manufacturing a narrative that gestures at truth, while quietly betraying it and reshaping public memory. Quoting Rahul Desai’s Dhurandhar review, “The term “fictional film inspired by real events” means that historical authenticity will be cited if the filmmaking is questioned, and fiction will be cited if the historical authenticity is questioned”.

Repeated enough times over the years, fiction eventually cements itself as perceived truth. Upcoming projects like Border 2 and Ramayana will unfortunately monetise this outrage, thriving neatly within an already polarised political and communal climate.

Sriram Raghavan once said, “A good war film is actually an anti-war film”, and it remains the ultimate litmus test for these so-called “pro-India” films. In a country that claims to love peace, these movies consistently promote the opposite: cultivating a generation of men stripped of empathy, saturated with hatred and Islamophobia, groomed for violence under the guise of cinematic spectacle. In the process, India’s democracy bleeds quietly, inching toward a slow erosion of secularism, while its people—reduced to echo chambers, mouthpieces, and instruments of persuasion—are turned against one another.

At a time when the country is choking on polluted air, unsafe water, a cost-of-living crisis, gendered violence, caste discrimination, and countless unresolved failures, it is stunning how the parameter of “love for the nation” is rerouted towards conveniently manufactured communal provocations. That distraction has worked far too well for far too long, and the least we owe ourselves is the critical ability to question what we are being sold—on screen and off it.

There’s a line in Dhurandhar that declares, “India’s greatest enemy is India itself; Pakistan comes second,” a provocation that feels half-true and fully revealing—how propaganda cinema often manufactures grievance to reassure a polarised audience of its own moral purity and perpetual victimhood. Art is not bound to its maker alone; it survives by inviting the audience to think for themselves and we’ve let our thoughts wander off for far too long.