A few years ago, on our way back to Kolkata from a weekend trip to Shantiniketan, we started playing the ‘Memory Game’ to do away with the boredom of the car journey. This game compels us to recall and repeat the many illustrious names from the past. For the Bengali psyche, each time we play it, there’s an unconscious urge to locate ourselves within the character-scape of a well-known Satyajit Ray film: Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest, 1970). Though the game isn’t central to the film, it becomes a curious point of connection—perhaps a deeply personal one as individuals, or a collective one shaped by our belonging to the urban Bengali middle class. Before getting into that layer of discussion, let me briefly delve into a few impersonal aspects of the film itself.

Cannes 2025| Revisiting Satyajit Ray’s Classic Aranyer Din Ratri

55 years after its release, a restored version of one of Ray's most incisive films will be screened at Cannes Classics tonight, in the presence of Simi Garewal and Sharmila Tagore.

Aranyer Din Ratri marks the beginning of Satyajit Ray’s cinematic journey through the 1970s—a phase during which he began to explore new thematic and stylistic territories. In the 1960s, with films like Kanchenjungha (1962), Mahanagar (1963), Kapurush (1965), and Nayak (1966), Ray examined and critiqued the post-colonial Bengali middle class in his liminal yet ingenious way. The following decade would bring his incisive Kolkata Trilogy—Pratidwandi (1970), Seemabaddha (1971), and Jana Aranya (1976)—where we witness middle-class youth reacting helplessly to their surroundings, like puppets in the hands of a larger, unyielding system. Released in 1970, Aranyer Din Ratri stands at this very cusp.

That year, the film competed for the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Now, 55 years later, a newly restored version will be screened at Cannes—an event made possible by the efforts of the Film Heritage Foundation.

Loosely based on Sunil Gangopadhyay’s novella of the same name, the film follows four young men from Calcutta—all in their late twenties—who retreat from the rules and regulations of job-centred city lives to the idyllic tribal forests of Palamau in Bihar (now Jharkhand). Brimming with confidence and a touch of arrogance to break all the norms of regular life, they encounter a few local tribal villagers and two urban women from a similar socio-economic background. These interactions compel them to confront their hollow, self-centred worldviews, steeped in colonial ethos, and gradually shed their city-bred personas—the typical Indian male ego, the pretence of modernity. In doing so, they begin to encounter the limits of their own identities.

The first ten minutes of the film set the tone and signal how Ray’s interpretation will differ from Gangopadhyay’s original novella. In the book, the quartet arrives in the forest by train, with no apparent distinction in their social or economic status. In contrast, the film opens with the four friends—Ashim (Soumitra Chatterjee), Sanjay (Subhendu Chatterjee), Hari (Samit Bhanja), and Shekhar (Rabi Ghosh)—traveling in an Ambassador car. Ashim, the unofficial leader of the group, is at the wheel. He appears to be the most affluent, holding an executive position in a corporate firm. Sanjay, who works as a labour officer in a jute mill, shows a marked interest in literature. Ray subtly introduces the quintessence of Bengali youth through Sanjay, as the film begins with his voiceover—reading from Palamou, the classic 19th-century travelogue by Sanjib Chandra Chattopadhyay. The iconic line, “Bonyera bon-e sundor, shishura matri-krore” (“The wild belong in the forest, just as children in their mother’s lap”), indicates the elite lens clouded in high culture through which the narrative shall unfold. While Sanjay reads aloud, Hari—the blunt and somewhat indifferent sportsman—sits beside him, disinterested in the trip and dozing off through much of the journey. And then there’s Shekhar, the most endearing to the audience: jobless, carefree, and full of comic charm, occasionally dabbling in racecourse gambling.

The nuanced traits of these four characters collectively reflect the broad spectrum of the Bengali middle class. The moment they turn to the local country liquor mahua, their inner selves begin to surface. Ashim, the flamboyant, aspiring upper-middle-class man, vents his frustration at having to constantly rub shoulders with high society. Sanjay, the conformist and conventional “good” boy, expresses his helplessness in living up to middle-class family expectations. Hari, heartbroken after being dumped by his sophisticated lover (played by Aparna Sen) for his emotional inexpressiveness, seeks comfort in alcohol and the uninhibited allure of the Santhali woman Duli (Simi Garewal). Only Shekhar remains sober—quietly watching over his inebriated friends, trying to keep them in check.

Their ruthless self-centeredness and indifference toward the poor is revealed in how they treat both the caretaker of the forest bungalow and Lakha, a local villager who becomes their temporary man Friday. Their decision to barge into the bungalow without a reservation exposes not only their immature and boorish desperation to escape into a pseudo-bohemian fantasy but also their complete disregard for the caretaker’s fear of losing his job should the forest officer discover he allowed them to stay without permission. Later, when Hari misplaces his wallet, his immediate suspicion falls on Lakha—who is entirely innocent. Without hesitation, Hari physically assaults the boy, only to be restrained by his friends.

Gangopadhyay’s characters, in contrast, were drawn with affection. The author portrayed these aimless young men with a degree of empathy, while Ray adopts a more critical stance—almost pointing a finger at this irresponsible, boyish generation of his time.

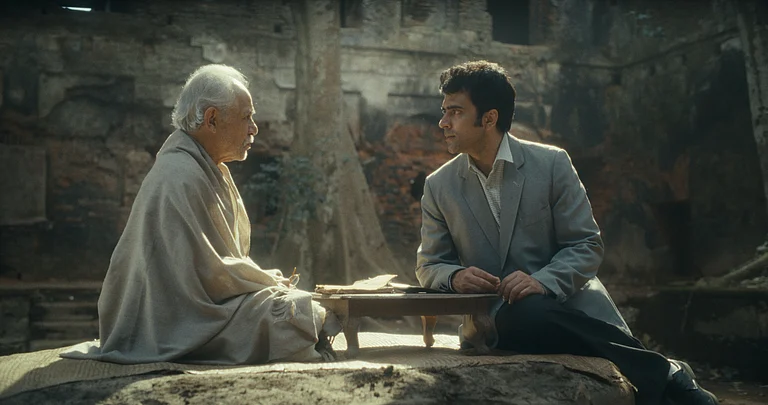

About thirty minutes into Ray’s narrative, the audience, through Shekhar’s gaze, gets the first glimpse of the heroine, Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), accompanied by her widowed sister-in-law, Jaya (Kaberi Bose). Well-read, poised, and elegant, Aparna possesses all the qualities that would naturally attract an educated, high-salaried, ambitious man. Ashim is quickly drawn to her, though the reserved Aparna manages to elude his curiosity, maintaining an air of mystery. In her presence, Ashim’s confidence is often unsettled—at times merely humbled, at others, completely shattered. Aparna, perceptive and sharp, pretends to lose at the memory game, even though she remembers the entire chain of names. This moment draws a striking parallel to Ray’s female characters—Aditi from Nayak and Tutul from Seemabaddha—who similarly hold up a mirror to successful, over-ambitious, yet vulnerable men.

The encounters of the other two men, Sanjay and Hari, with Jaya and Duli respectively, are starkly different. The so-called ‘good boy’ Sanjay isn’t able to respond to Jaya’s sensuous advances, restrained by the deep-rooted inhibitions of his middle-class upbringing. Hari, in contrast, offers Duli money to slip away with him into the solitude of the jungle for physical intimacy. The forest’s atmosphere can’t sway Sanjay to cross the boundaries he’s internalized, but Hari is all too eager to shed his ‘bhadralok’ facade, releasing the frustration that has built up after being spurned by a posh Calcutta woman. But the jungle exacts its own price. Just as Hari indulges in the thrill of transgression with Duli, Lakha attacks him from behind, seeking revenge for the past insult. Hari falls unconscious, and this time Lakha takes his wallet—setting aside his usual sense of honesty, a virtue the city’s middle class would never have acknowledged anyway.

Revisiting Aranyer Din Ratri compels one to reflect on the nuanced yet subliminal class conflicts and urban–rural divides that Ray so intelligently etched into both his script and visual storytelling. When an intoxicated Hari gazes at Duli’s body, Shekhar mockingly refers to the Santhal woman as "Miss India"—a moment steeped in irony and condescension. Later, we rediscover Duli through Hari’s gaze from the swinging top-angle view of the Ferris wheel at the village fair—a perspective both distant and undulating. Ray masterfully intersperses vast, wide shots of the forested landscape with intimate close-ups of faces marked by dilemma, desperation, greed, and selfishness. Then there are the much-discussed camera-sweep movements, gliding from one face to another during the memory game, and the innovative title card that turns each word into a window to the forest itself. And how can I not mention one of the most talked-about moments—the burning of The Statesman newspaper, as Shekhar delivers the striking line: “Sabhyotar songe somosto somporko sesh” (Here’s to cutting all ties with civilisation). Even the theme music, composed by Ray, hints at something mysterious, forewarning that not every corner of the forest is meant to be explored.

But ultimately, it’s the memory game sequence that continues to resonate, triggering a shared, almost collective memory whenever the film comes up in conversation. The game serves both as an excuse to reminisce about a glorious past and as a subtle performance—an exhibition of one’s intellectual capital, flaunting knowledge of big names across disciplines. When Aparna casually mentions “Kennedy,” a visibly competitive, eager-to-impress Ashim jumps in to ask, “Which Kennedy?” Aparna replies coolly, “Bobby”—as if saying the more obvious “John F. Kennedy” would have been too predictable, hence uncool.

That quiet performance of cultural pretence—elegant, ironic, and slightly self-conscious—still lingers in the Bengali middle-class psyche Ray portrayed so incisively 55 years ago.

Debarati Gupta is a Filmmaker, Columnist & Guest Lecturer at Calcutta University

Tags