It is now four days since the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal put out its unanimous final award. Everything has been happening as anticipated in Karnataka: Life was crippled for a couple of days; schools, colleges, business establishments downed shutters; Tamil migrant labourers quickly took a bus out of the state to their perceived safe havens; MNC buildings spread nets to prevent arsonists from damaging their glass facades; vegetable prices shot up; stage-managed protests are happening;'bandh' calls are being issued and there is a crawling sense of fear that large-scaleviolence may break out any moment.

But amidst all this, there is something that has not happened, something that has not followed the formulaic script for such occasions—there has been no official reaction to the award from the state government. They do not seem to know how to react and even the all-party meet that was held on Wednesday was inconclusive. All that has been said so far is that they need to study the 1000-page document before they react. And everybody can see through this thin veil of excuse. The government is in a Catch 22-situation and its unease isconspicuously glaring. This is in total contrast to how the Tamil Nadu government has reacted to theaward: by giving it a spin of victory that makes the other riparian states, especially Karnataka, look losers. Their sense of victory also comes from the fact that they had put up the Cauvery dispute as 'priority' in the Common Minimum Programme when the United Progressive Alliance came into being at the Centre in 2004 and they can nowclaim to have fulfilled a promise.

But why is Karnataka unable to react? Is it because the judgment is fair? Or is it because there is no course correction possible constitutionally and this is the feared dead-end? It looks like there is an element of both and there is also a third factor to which we will come first, because it seems to be the biggest hurdle at the moment for Karnataka.

The third factor is the shrill sub-nationalistic pitch that surrounds the Cauvery dispute. Over the decades, the political class in Karnataka have come to occupy an unrealistic perch on the issue, climbing down fromwhich now, when the award is not entirely to their expectations, is clearly seen as political suicide. And what were their expectations? It is difficult to say, because the issue has always been submerged in the din of rhetoric.

Cauvery may be a river confined to the South of the state. Its basin districts are just eight out of the 27—Kodagu,Hassan, Tumkur, Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Kolar, Mandya and Mysore. But then, it has become central to the pan-Kannada identity. Popular media and even classic literature has constructed the river in the minds of the masses as a 'life-giving mother' and therefore anything to do with sharing it is confronted with plain unreason and a macho-feudal violence. Hence, in the last few days, everybody, from litterateurs to lawyers, think of it as their duty to 'save' Karnataka by rejecting the award.

When Girish Karnad said that we had to "accept the tribunal award," it was seen as'betrayal'. There were protests outside his house. They demanded that he should return his Jnanpith because he was not being 'loyal' to Kannada and Karnataka, which had fetched him thecrowning literary glory. A few others said that he was 'insensitive' about the Cauvery issue because he had lived for two decades in Chennai (referring to his OUP job). Whatwas implied was that his loyalties were misplaced. This statement was pure provocation for a lynch mob, but there was, luckily enough, police protection. The reception that Karnad's statement received is a warning to anybody else who wants to take a pragmatic view of the final award. This is the pitch and the perch from which Karnataka's politicians find it difficult to climb down.

At every bend in recent political history, politicians rode the Cauvery wave in the Mysore region to win votes and now when they suddenly cannot use the issue anymore, they face the difficulty of going back empty handed and facing their constituents. Because their old rhetoric is no longer valid. On the other hand, if they had only prepared their constituents to the idea of sharing the yield of the river, perhaps they would not have been in the situation they currently face. This is precisely why there is no reaction.

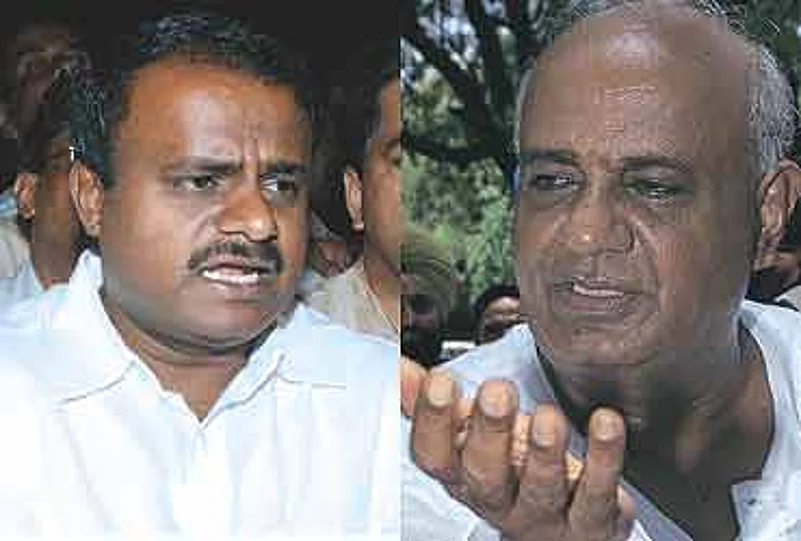

Politically, the Mysore-Mandya-Hassan-Rural Bangalore region is the epicentre of the dominant land-owning Vokkaliga community. Deve Gowda, S M Krishna and others belong to this community.The region greatly influences the formation of the government in Bangalore. There is no issue greater than Cauvery (which irrigates their lands) for this community and if now that issue is being shaken at its roots, political parties have to wonder about new electoral alignments that will take shape. One example from the 2004 elections should indicate the great import that the Cauvery issue carries politically in the region. The then sitting CM S M Krishna could not recontest his Maddur Assembly seat in Mandya district, because there was a strong perception among the people of the region that he had let them down during the 2002 Cauvery crisis. What will happen to Kumaraswamy, whose constituency Ramanagaram is in Bangalore Rural, if he is seen conceding on the Cauvery issue is anybody's guess. His father represents the Hassan Lok Sabha seat and his brother, H D Revanna, is a legislator from Holenarispur again in Hassan. So, in a way, it is about the political future of the ruling family and they should be seen fighting back on the issue and not meekly submitting to the final tribunal award. But theydo not seem to have a strategy in place as yet.

There are hard realities that confront the state government before it makes any statement of rejection. Any questioning of the legal validity of the award or even a slightest law and order problem may jeopardise Kumaraswamy's government. As a reminder, there is the case of what happened to former CM S M Krishna in September2002. The SC had then issued a contempt notice for non-compliance of an order to release Cauvery water to Tamilnadu. Krishna had backtracked and apologised to the apex court.

Interestingly, Karnataka has always been opposed to the disputes tribunal. After all it wasconstituted at the request of theTamil Nadu government. When the tribunal made an interim award in 1991, the then state government passed an ordinance rejecting the validity of the award, but the Supreme Court had held the ordinance to be ultra vires. Violent protests ensued in Karnataka and as a result 25 peopledied — as per official records. Similarly, S M Krishna in 2002 ignored the order of the Cauvery River Authority (a body set up to implement the tribunal award) to release 0.8 tmc ft of water, but then had to backtrack after the SC intervened. So each time Karnataka has tried to show some bravado it has misfired. So this time around there is a great deal of caution and hence the absence of instant reaction.

Karnataka has said that it would "appeal" against the award, but the question is can there really be an appeal under the provisions of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act of 1956, which clearly equates the award to "an order or decree of the SupremeCourt"? The award only has to be published in the gazette and it becomes binding on the riparian states. The state can only ask for further "clarifications" on the award in the intervening period. Also, since the state cannot attribute motives to the award, rejecting it would mean admitting to failure of effectively presenting its own case in the last 17 years of proceedings. There is also the embarrassment for the state government that its senior counsel on the tribunal, Fali Nariman, spoke positively about the judgment. He had said on Monday that "the judgment is good, it is satisfactory for allparties". In the Assembly, on Wednesday, the government instead of battling theopposition and the award was battling this statement of Nariman.

Another reason as to why the state government is speechless is that its chief complaint has been adequately countered by available statistics. The state's unhappiness about the final award has been about the annual quantum of water release toTamil Nadu from the state—192 TMC ft. During the period of interim award it was higher at 205TMC ft. But the 15-year data available on the quantum of release at the inter-state contact point of Biligudlu says a different story. There have been only two major crisis years between 2002 and 2004, when the state could release only 109.45TMC ft and 75.87 TMC ft respectively due to severe drought. Otherwise, the state has released water at an average of 230TMC ft, more than what was prescribed by the tribunal. As recently as 2005-06, the state released 383.91TMC ft of water and in 1994-95 it was as high as 394 TMC ft of water.

A finer point in Karnataka's argument is that the allocations for months between July and October are very heavy. In August the state is expected to release 50TMC ft of water. But this heavy release, perhaps, takes into account that the South-East Monsoon would be active between June and September. The quantum of release gradually reduces when the North-East Monsoon (between October and December) that benefitsTamil Nadu arrives. Also the award clearly makes a provision for a distress year. It says: "The allocated shares may be proportionately reduced." If the state has questions on this front it is well within its rights to seek a clarification from the tribunal.

There are other positives for Karnataka in the award but no politician wants to count them. The ceiling on cultivation, which stood at 11.20 lakh acres has been increased to 18.85 lakh acres; new projects to harness the water, hitherto stopped, have been allowed and the the state has been delivered from the clutches of two agreements of the colonial era (1892 and 1924) between the then governments of Mysore and Madras. But JD(S) MLA and the state's special representative in New Delhi, Mahima Patel, toldOutlook: "We wanted to cultivate 22 lakh acres, but with the water allocated to us we can cultivate only 14 lakh acres. The rich groundwater available inTamil Nadu has also not been taken into account by the tribunal." One is not sure if these numbers are an afterthought and is all about shifting the goal post.

Of all the positives there is one in particular that needs to be highlighted. And that is the chance to correct the historical wrong caused by the agreements of 1892 and 1924. The historical wrong was not that these agreements were effected by prioritising the irrigational interests of the then Madras state under British administration as against the princely state of Mysore, but the fact that it sowed the seeds of hatred between two neighbouring and friendly peoples. The stereotype of Tamil-Kannada hatred that we commonly encounter can perhaps be traced to these two agreements of the past century. The hatred is often mistakenly linked to linguistic issues, but it is Cauvery that is at the core. Besides many other things in fine print, the 1892 agreement said that Mysore should not erect any new irrigation reservoirs across the Cauvery without prior permission of the Madras state. As per the 1924 agreement new irrigation was stipulated to 110,000 acres. These were two agreements made between asymmetrical powers, but continued to have a bearing wellup to the present times. But now, the final award of the tribunal "supersedes" the agreements "so far as it is related to the Cauvery river system". In this context, there has to be some visionary and statesmanlike effort to rebuild the bridges between the Tamil and Kannada peoples, who are now two equals of a federal polity.

As long as the political class in Karnataka views the Cauvery dispute as a rights issue of an upper riparian state and not as an effort at equitable sharing of water within the constitutional framework, the resolution of the dispute will remain a far cry.