Religion was the compelling moral force that propelledplanes into buildings on September 11, 2001. To understand why the carnage tookplace, some level of understanding of this moral force is essential. For thosewho are religious, and who do not support the overwhelming use of violence, thismoral force can be written off as a mutant strain of religion, blatantly wrong,and quite different from their own understanding. For those who are skeptical ofreligion, or hostile to it, this moral force can be viewed as yet anotherindicator of the irrational and perhaps dangerous basis of religion, not tospeak of its capacity to rouse people to commit atrocious acts with the moralinsulation of alleged divine justification. For instance, Richard Dawkinsopined, "To fill a world with religion, or religions of the Abrahamic kind,is like littering the streets with loaded guns."

Interestingly, both perspectives prioritize this moralforce as some other peoples' force, who are unsurprisingly seen as dangerous andpossibly quite mad. Someone else's ignorance, someone else's craziness, is infocus. While convenient, this approach is not useful. For the religious, it doesnot encourage reflection on how commonly held religious understanding may wellbe implicated too, including beliefs they themselves may hold dear. For theskeptical or hostile, it becomes all too easy to write off religion and eventhose who are religious as one of the primary problems, at the expense ofmissing significant efforts that contribute to genuine, constructive peacebuilding.

Both perspectives are inadequate if we are to take peace,and quite likely our survival, seriously. Instead, genuine critical inquiry intothe nature of this moral force is a vital step if we are going to collectivelylearn from September 11, and help prevent such tragedies in future.

A look at how movements in Afghanistan and Pakistan haveused religion when clamoring for socio-economic and political change is aninteresting place in which to start, beyond the obvious reason that the allegedperpetrators of the carnage hold base there. It is also an area where Westernpowers have had a major impact, through formal colonization and subsequentpolitical, economic and military interventions. Its people have a vigorous senseof Muslim identity.

While we could focus attention on the Taliban, who emergedin the mid 1990's, with their extreme interpretation of Islam based on SaudiArabia's official state religion Wahhabism, for a number of reasons it is moreuseful to turn to earlier movements. For a start, the Taliban were nurtured andfully backed by the Pakistani government. The Taliban violently seized power ina war-ravaged country rendered susceptible to state-sponsored totalitarianism.In Pakistan itself, meanwhile, such extreme religious interpretations arepopular for only a minority of the population. The Pakistani government used theTaliban to further its own economic and political goals in Afghanistan --certainly not for any concern of Islamic purity. While studying theTaliban is useful to see how extreme fanatics can use religion, it is arguablymore useful to understand how more mainstream interpretations allow extremiststo emerge using religion to justify their fanaticism.

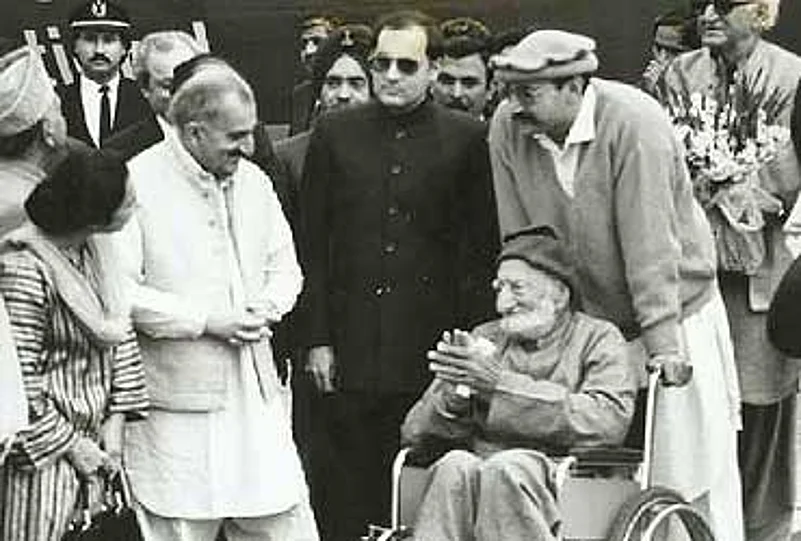

Instead of focusing on the Taliban, we can turn to a coupleof earlier movements in Afghanistan in Pakistan that explicitly drew uponreligion. The first is the Afghan Jihad against the Soviet Union, whichcontributed decisively to the conditions that led to the Taliban's emergence.The second, a remarkable nonviolent Muslim movement against British colonialrule in the northwest of Pakistan, is strikingly different. In this article, wewill take a look at the lives of two individuals who led these movements --General Akhtar Abdur Rahman Shaheed, and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan -- for someperhaps surprising lessons. Both men were distinguished soldiers, and are littleknown outside the region.

The Silent Soldier

General Akhtar, 1924-1988, lead the Afghan Jihad against the Soviet Unionand associated Afghan communist regime. He was Director-General of the ISI,Pakistan's equivalent of the CIA, from 1979-1987. Unlike the CIA, the ISI isresponsible for domestic as well as international spying and covert operations,with its leadership consequently feared by many, including much of Pakistan'smilitary. Given the length of Akhtar's tenure, and the power of the position, hewas a central figure in military dictator President Zia-ul-Haq's administration.

Of East Punjabi descent, Akhtar joined the military in 1946as a young man, and after the partition of India, and subsequent creation ofPakistan, was to fight in three wars against India. Introspective in nature,Akhtar preferred anonymity to being in the public eye (unlike some of hismilitary colleagues), and was referred to by colleagues as the silent soldier.

Drawing upon his extensive military experience andknowledge of tribal culture and methods of fighting, Akhtar planned and directedthe Afghan Jihad, supported by American, Saudi and to a lesser extent, Chinesefunds. Akhtar worked closely to carry out the Jihad with CIA head William Caseyin an atmosphere of mutual trust and cooperation. Casey apparently shared withthe Afghan Mujahideen leaders a deep respect for Akhtar's military cunning anddemanding personal leadership. Akhtar would often tell the Mujahideen leaders,"Kabul must burn." Some 70% of American funds for the Mujahideen wentto Islamic extremists, again not for reasons of religious purity, but because ofthe extremists' wartime effectiveness. Ultimately, Akhtar was the only militaryleader since World War II to take the Soviet Union on in the battlefield andinflict vast and telling losses.

Akhtar explicitly acknowledged to Zia-ul-Haq while planningthe Afghan Jihad that it would be seen as having a compelling moral force.Indications are that he not only viewed this as a useful propaganda weapon, butthat he faithfully believed it himself, for he drew upon his Muslim faith andidentity throughout his military career. India's partition influenced this whenhe was almost killed by Hindus while on duty because he was Muslim, being savedonly by the arrival of fellow Muslims. According to a Brigadier who workedparticularly closely with him during the Afghan Jihad, the massacres of Muslimsby Hindus and Sikhs during partition was "never forgotten and neverforgiven," and for the rest of his life, "he regarded India as animplacable enemy, both of his country and his religion." A fellow militaryofficer, recalling an incident in the 1970's, remarked "One evening we wereout together in a forward locality, and from my vantage point we could clearlysee a big town in Indian held Kashmir. He stood there and stared at the town fora long time. The lights in the houses were coming on one by one. He ground histeeth and said, 'if only once I get the orders you will see what I do.' Hewalked around like a caged lion ... his own eyes reflected the intense feelinghe felt for the pain and suffering of his fellow Muslims over there."Akhtar's great ambition, said the Brigadier, was "that after the Sovietdefeat he would be able to visit Kabul and offer prayers to Allah for freeingthe city from His enemies."

The Nonviolent Soldier of Islam

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, 1890-1988 (Akhtar died the same year), was anonviolent soldier who fought for freedom and justice for more than 70 years.Incredibly, he raised a large nonviolent Muslim army to fight British colonialrule from the midst of a proud and largely tribal people, the Pathans (alsoreferred to as Pashtoons or Pakhtoons), who had a renowned history of fightingusing handmade guns, daggers, and at times outrageous cunning. This army, calledthe Khudai Khidmitgars ("Servants of God"), remained resolutelynonviolent in the face of severe repression and humiliation from Britishcolonial rulers. The British violence was of similar savagery and intensity tothat which the Taliban has dished out in the last few years, except it lastedfor many decades. There were no pretensions of "civilized" warfare forthe British: in the words of one of their 1930 reports, "The brutes must beruled brutally and by brutes." The British regarded the area, the NorthWest Frontier Province, as being of great strategic significance, as it was thegateway to India, and they wanted their crown jewel colony to remain under theircontrol. The last thing they wanted to see were organized, unified Pathans. ThePathans, meanwhile, had a burning desire for freedom. So the British cut downthe Khudai Khidmitgars with ruthless violence, and tried to sow dissension amongthe Pathans through divide and rule, using their usual methods of bribery andcoercion.

Khan's achievements in leading the Khudai Khidmitgars arenot easy to overstate. It was astonishing not only that they could remainnonviolent in the face of such horror, but also that they should do so to beginwith, given their warlike way of life and easy access to weapons. As Britishviolence like mass shootings, property destruction, and torture (includinggenital torture) was inflicted, the Khudai Khidmitgars' numbers increased,swelling to around 100,000. Jawaharlal Nehru, who later became India's firstprime minister, was stunned by the Khudai Khidmitgars' nonviolence, and found itincredible that "the man who loved his gun better than his child orbrother, who valued life cheaply and cared nothing for death, who avenged theslightest insult with the thrust of a dagger, had suddenly become the bravestand most enduring of India's soldiers."

One striking characteristic of Khan throughout his lifetimewas his dogged determination to represent the truth, even at great personalexpense. As an old man, flying in the face of official propaganda he declaredthe war in Kashmir was not a Jihad but a façade, hardly endearing himself tothe many thousands of Pakistani families who lost their sons in the war. As ayoung man, when looking for opportunities to serve his people, he began byopening schools and organizing people socially. He was arrested, and broughtbefore a deputy commissioner who wanted to know why officials had allowed him toreturn to the country after he had gone on pilgrimage to Afghanistan. Khanreplied, "First you take our country from us and now you won't even let uslive in it?" For this, he was imprisoned three years at hard labor. He wasto endure a total of 15 years in British prisons before partition, and a further15 years in Pakistani prisons after partition, more than one-third of his adultlife (and more than Nelson Mandela).

Khan took on not only British imperialism, but looked witha critical eye at his own society, and encouraged reforms. He rallied againstthe privilege and power of the big landlords and worked to dismantle the localcaste system, saying ordinary, working people such as craftsmen should be ableto own land. He was almost killed by resentful landlords for doing so. Hedirectly confronted religious ignorance, like the belief that children whoattended school would go to hell. He wanted to see women play their rightfulrole in society, instead of being crushed by the burden of tradition andneglect.

The Khudai Khidmitgars were formed from a largelyilliterate society, so in addition to publishing a journal, the Pakhtun, in theearly years Khan spread his message of sacrifice, work and forgiveness bypersonally visiting 500 Pathan villages. While his people may not have beeneducated, they could recognize selfless action when they saw it. Khan valuedselfless service to others as a foundation of religious action. He wrote, withthe authority of his life's example, "Religion is also a movement. Ifselfless, undemanding and holy men and women join this movement and dedicatethemselves to the service of their country and the people, this movement isbound to be successful. Such people will be a blessing to mankind. Through theircontribution their country and their people will flourish and prosper."

Most of all, Khan directly challenged the role of revengein society. The culture of the Pathans was tribal, and as Eqbal Ahmad pointsout, "The tribal code of ethics consists of two words: loyalty and revenge.You are my friend. You keep your word. I am loyal to you. You break your word, Igo on my path of revenge." Pathans were long adherents to taking revenge touphold honor, being somewhat notorious for engaging in bitter family and tribalfeuds that could last generations. Khan directly appealed for his people toforgo revenge, and adopt nonviolence. It was an explicit precondition of joininghis army. In a society where not to take revenge, and therefore lose one'shonor, was considered worse than death, this was a stunning achievement.

LESSONS TO BE LEARNT FOR THE PRESENT

What lessons can we learn from the lives of General Akhtar and Abdul GhaffarKhan and the movements they were associated with if we are to take peaceseriously? That is, what do their respective approaches to resolving conflictsand achieving justice tell us about how we can move forward in the presentsituation?

Combating Communalism

The first, and most obvious lesson to be learned is that when religion isviewed as being communal, it can be rapidly be turned into a highly destructiveforce."Crowd psychology is a blind force," wisely remarked renownedIndian literary figure Rabindranath Tagore. "Like steam and other physicalforces, it can be utilized for creating a tremendous amount of power. Andtherefore rulers of men, who out of greed and fear, are bent upon turning theirpeoples into machines of power, try to train this crowd psychology for theirspecial purposes. They hold it to be their duty to foster in the popular minduniversal panic, unreasoning pride in their own race, and hatred ofothers."

While the same communal forces that almost killed Akhtar atthe time of India's partition were overwhelming much of Northern India, theKhudai Khidmitgars patrolled their communities protecting people who belonged tominority religions, saving many lives.

Communalism builds on the belief that one religion issuperior to another, or the belief that religious truths are mutually exclusivebetween religions. These beliefs are in fact the official doctrinal positions ofmany religious institutions, all of which claim to be speaking with divineauthority. For many believers, they are a common sense truth about theirbeliefs. Khan specifically opposed such brazen foolishness. He proclaimed,"My religion is truth, love, and service to God and humanity." It washis "firm belief" that all religions are based on the same truth, andshould be given equal respect. He remained a devout Muslim while eager to learnfrom other religions. Regarding those who promote communalism--of which he saw agreat deal in his life, and the vast suffering it inflicted--he commented"those who are indifferent to the welfare of their fellowmen, those whosehearts are empty of love, those who do not know the meaning of brotherhood,those who harbor hatred and resentment in their hearts, they do not know themeaning of Religion."

The fact is, beliefs of religious superiority are a primetarget for extremists to expropriate and twist into their terrible logic. Ifinstead religious believers held a common notion that beneath the surface, allreligions teach much the same--naturally with differences reflectingtemperament, culture and time--then it would be nonsensical for extremists toclaim that alleged divine wrath is on their side. Only fools would take themseriously.

Rejecting Revenge

As we have already noted, Akhtar was unable to forgive Hindus and Sikhs whenthey massacred Muslims (just as many Hindus and Sikhs were unable to forgiveMuslims when they were likewise massacred). Instead he worked to strengtheninstitutions that depend fundamentally upon revenge, just as the U.S. andBritish governments are currently doing. The leaders of the Taliban do the samethemselves.

Much of the time the U.S. and British governments hidetheir vengeful focus behind language like "retaliatory strikes," or"bring the perpetrators to justice," and so forth, but revenge isessentially their focus. Ditto for the Taliban. The three are determined toconvince respective recipients of their propaganda that this path is the onlyeffective way forward to provide security and make up for the death of theirpeople, irrespective of their falsehood.

It is wise, however, to learn from the experts on revengebefore confidently asserting this to be true and proceeding to kill people. ThePathans are experts on revenge. They practiced it fearlessly for hundreds ofyears, against outsiders and amongst themselves. They celebrated it in theirpoetry, sang of it in their songs. Presumably all cultures are familiar withhusbands taking revenge against adulterous wives and their lovers by killingthem, but how many have tales of women rallying their menfolk to take revengelong after the men have been exhausted by it? The huge numbers of Pathans whojoined the Khudai Khidmitgars did not give up revenge simply because theyadmired their leader.