Did you know that the Mahatma who led India to independence in a loincloth used to dress elegantly in a top-hat and tailcoat as a young trainee barrister in London, but wore no underwear to save money on laundry? That’s the sort of unexpected detail you can expect to find in Ramachandra Guha’s exhaustive, 600-page chronicle of the first half of Gandhi’s life.

Of all the world’s leaders, Gandhi has probably attracted the largest volume of biographical writing. It began in the ’50s, with the monumental eight-volume, official biography by D.G. Tendulkar, followed by the brilliant and very concise Life of Gandhi by the American academic, Louis Fischer, who had the advantage of interviewing him in his lifetime.

Many others have trodden the path since then, drawing on the huge corpus of Gandhi’s memoirs, letters, articles and speeches, which fill 98 volumes of the Collected Works. The key enigma which both attracts and defies his biographers is how a Christ-like ascetic, so obsessed with the rejection of all that is worldly and material, could so successfully capture and wield enormous political power over a subcontinent as diverse as India.

Past biographies have ranged from reverential eulogies to the iconoclasm of a new generation of Western historians, who have tried to demystify the Mahatma, revealing him as a wily and manipulative politician with a penchant for dubious sexual experimentation with young virgins. Guha enters this biographical minefield with the avowed aim of presenting a more holistic portrait than his predecessors, relying less on Gandhi’s own autobiographical writings and more on previously neglected press records and the narratives of people around him.

Guha is one of India’s most intelligent and readable historians, and in addition to his considerable talents, he has had the good fortune to discover a treasure trove of Gandhi’s own voluminous press cuttings and also many shelf-loads of letters to him from friends and colleagues, lying forgotten at the bottom of book-cases in the Gandhi Museum in Delhi. With all these new primary sources, Guha decided to expand his project into two hefty volumes. His main contention is that previous biographers have adopted a teleological approach, too hastily skipping over Gandhi’s earlier career in order to focus on his later years at the helm of India’s independence movement.

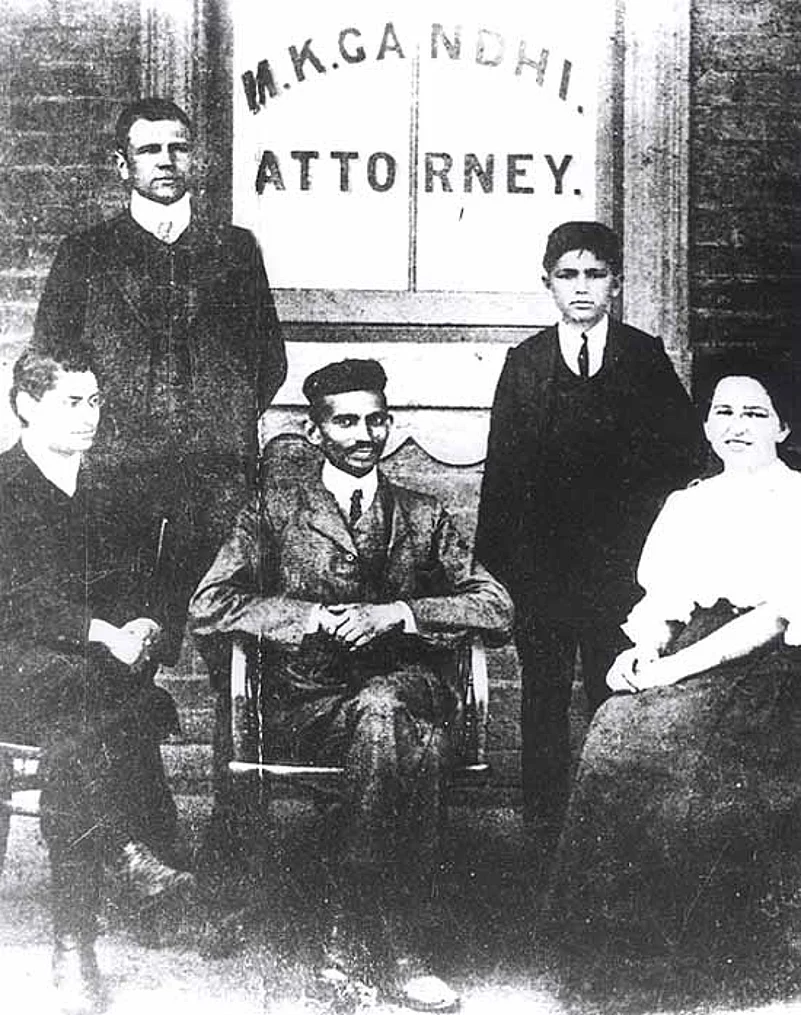

Guha redresses the balance by lingering with painstaking detail on those youthful years when, through a process of trial and error, Gandhi developed his very distinctive technique of passive resistance against the emerging apartheid regime in white-ruled South Africa. We begin with his poor performance at school in provincial Gujarat and follow his more glamorous education in London, where his main passion was not politics but evangelical vegetarianism.

Gandhi returned to India with a taste for cocoa and oatmeal, but his poor public speaking skills contributed to his failure as a barrister at the Bombay High Court. Hence his decision to seek his fortune in South Africa, which was then a powerful magnet for aspiring young Indians, attracted as much by its glorious climate as its rapidly expanding professional and commercial opportunities. Here he was more successful, both as a lawyer and as the spokesman of an Indian diaspora united by the racist immigration, residence and employment restrictions imposed on them.

Gandhi’s own racial attitudes were, at the outset, no more enlightened when it came to black Africans, “raw Kaffirs”, as he termed them, “whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with, and then pass his life in indolence and nakedness”. But his years in South Africa encouraged him to break with caste taboos and to live and work closely with Indian communities as diverse as the predominantly Muslim merchant class, Tamil labourers and his own fellow-Gujarati Bania shopkeepers. He also acquired some very close white Jewish friends and colleagues, among them two militant feminists.

Guha’s account of Gandhi’s daily life is often painfully detailed, with long descriptions of his latest dietary fads, the bowel movements that resulted and even a loose molar caused by eating too many nuts. We experience, almost first-hand, the oppressive obsessions with food and excrement, dress and sexual hygiene, which he imposed so ruthlessly on the idealised residential communities he created, inspired by the romantic, back-to-nature anti-industrialism of Leo Tolstoy, whom he admired enormously. On the advice of his editor, Guha also expands on the lives of Gandhi’s disciples, which often makes the narrative unnecessarily discursive and overpopulated with minor personalities.

Guha neither censors nor censures the budding Mahatma’s frequent megalomania and his increasingly autocratic and even brutal treatment of his own wife and children. He castigated his conventional Gujarati wife, Kasturba, for her caste prejudices and almost threw her out of the house for refusing to empty the chamber-pot of his low-caste Tamil clerk. She was not consulted when he added sexual abstinence—brahmacharya—to his growing list of household rules and tried unsuccessfully to impose it on his sons as well. When Kasturba fell critically ill, Gandhi wrote explaining that he could not give up the political struggle to be with her, but cheerfully urged her not to feel guilty about pre-deceasing him if death should take her. Released from prison, he was outraged to find the poor woman, now severely anaemic, being dosed with beef extract by her sensible Parsee doctor. Though warned that she might not survive the journey, he insisted on moving her in torrential rain back to his own Phoenix Colony, where he subjected her to a naturopathic regime of cold baths and a fruit diet. Miraculously, she survived and later earned his respect by courting imprisonment herself.

The domestic tyrant proved far more flexible and pragmatic in his burgeoning political career. His religious eclecticism made him particularly receptive to Christian ethics and to Christ’s personal example of self-sacrifice in the face of oppression. Guha credits Gandhi with inventing passive resistance—or satyagraha (truth force), the Sanskrit name he coined for it—as a new and lasting global force for peaceful political change, as relevant today in Burma, Tibet or the Arab world as it was in early 20th century South Africa. But as Guha’s own account demonstrates, Gandhi adopted passive resistance lock, stock and barrel from his Nonconformist Quaker and Baptist friends; and it is surely somewhat fanciful to claim that Gandhian non-violence has played any part in the predominantly Islamist and often violent convulsions of the so-called Arab Spring. Satyagraha could only succeed against a regime which, however unjust, had a moral conscience and some respect for individual freedom and the rule of law. It would have been as useless in Hitler’s Germany or Stalin’s Russia as it was in China’s Tiananmen Square.

Gandhi’s own South African campaigns were remarkably restrained and moderate, his demands confined to freeing Indians from troublesome residence and immigration controls. Courting arrest by violating the race laws was a pressure tactic which did not prevent Gandhi from rallying to the imperial cause and organising a volunteer Indian ambulance corps, first during the Boer War in 1899 and again in 1906, when the authorities suppressed a native Zulu revolt.

Guha aims to present “a many-sided portrait” of his subject, including the views of his adversaries. But apart from the predictably hostile diatribes of white racists, the narratives he gives us come almost entirely from admirers. There are two exceptions, both of which foreshadow major flaws in Gandhi’s future leadership of the independence movement back home. “It is no easy task for a European to conduct negotiations with Mr Gandhi,” wrote Lord Gladstone, governor-general of South Africa. “The workings of his conscience are inscrutable to the occidental mind and produce complications in wholly unexpected places. His ethical and intellectual attitude, based as it appears to be on a curious compound of mysticism and astuteness, baffles the ordinary processes of thought.”

The second and more damning verdict came, on the eve of Gandhi’s return to India, from one of his own former Muslim colleagues, who accused him of gaining only one-and-a-half of the four demands for which they had been campaigning so long, leaving them “with the battle to be fought all over again”.

If South Africa was a laboratory for Gandhi to develop satyagraha, it was also a warning that his tyrannical obsessions with trivia, his sanctimonious mysticism and his resort to fasting as a form of emotional blackmail could be counter-productive and divisive. These are themes which will no doubt loom large in Guha’s second and final volume; and the general reader will welcome less undigested raw material and more of his own succinct historical judgements and insights.