Rt-Hand Unorthodox

Shahid Afridi, Pakistan’s skipper, is on top with some spin zing

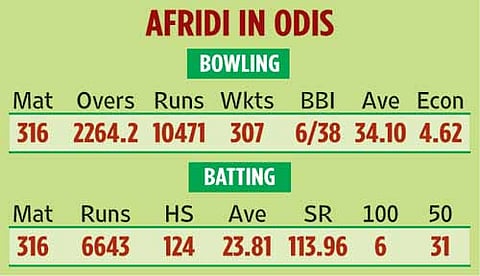

In this World Cup of astonishing performances and heart-crushing upsets, Afridi’s dominance of the bowling tables must count among the big surprises. His accuracy is nagging, his spin and googlies often unplayable, the variation of pace and bounce bewildering. Famous for his towering sixes, his blistering centuries, who could have ever predicted, a few years ago, that Afridi would become a wizard with the ball? In Outlook’s story on spin bowling last week, three maestros of yore—Abdul Qadir, Iqbal Qasim and Maninder Singh—rated Afridi as the best spin bowler on display. Pakistani bowling coach Waqar Younis told Outlook, “He’s won three games out of four for us. Need I elaborate more?”

Afridi attributes his astonishing success with the ball to his dogged focus on line and length in Sri Lanka, and to the fact that he is confident of repeating his performance as the tournament progresses. Sure, the Lankan tracks have helped, but Afridi points out, “In last three-and-a-half years, Alhamdulillah, I’ve been taking more wickets than genuine bowlers.” He’s pugnacious, mocking those who had rubbished him. “There are many ex-cricketers in Pakistan who are against me...but now the same guys are sitting on TV shows and saying good things about me. The main thing is performance, that’s how I can keep those guys quiet,” he says with candour.

You would be tempted to conclude that Afridi had changed, become quieter, less susceptible to mood swings, angry one moment and then smiling toothily, calculated, even diplomatic. In the past, he was an emotional bubble that would burst with disastrous consequences. In 2005, for instance, Afridi was banned from two ODIs and a Test against England for deliberately spoiling the pitch. Again, in January last year, he was banned from two matches in Australia for chewing on the ball. About these incidents, he says, “What I did was childish. Whenever I think about those things, I feel really ashamed and guilty. As a captain you are a more responsible person, you have to set examples for others.”

Some, particularly the bowlers, would think he takes his captaincy too seriously. He tends to accompany his bowlers as they walk to the top of their run-up, chatting animatedly, proffering advice, at times admonishing them. And he does it every ball, prompting commentator and former player Wasim Akram to comment that it must be irritating for bowlers. Afridi doesn’t agree. “Some people only listen when you speak to them that way. Some people need a stick, you know. But away from the field, I am more like a brother to these guys. They are all enjoying it with me,” he says.

Abba Afridi should have thought of applying the stick at the time Shahid neglected studies to play cricket, considered disastrous for a business family which also boasted of a few senior army officers. Instead, his father sent Afridi to a lowly government school, hoping to shame him into sitting at the study table. Afridi says, “I started playing cricket after seeing Imran Khan on TV. I was in Class V in Federal Secondary School, Karachi. My father was against me playing, standing in the sun and getting tanned. At that age you think of girls, I was only thinking of cricket.” As others told Afridi senior about his son’s skills, and as the budding cricketer graduated from under-14 to under-16, he relented. A star was born, soon becoming the poster-boy of Pakistani cricket.

Now 31 years old, Afridi still remains adamant about sticking to his style of play. For instance, many had tried to persuade him to apply himself to take advantage of his prodigous batting talent. Afridi explains, “I tried to go there and play like a classic cricketer, but you can say I am not mentally strong enough. I now don’t want to change my batting style. Sometimes I perform, sometimes I don’t. Attack is my strong point. I tell other batsmen to just go and play their natural game.”

Elsewhere, he’s a natural as well. He says he stopped playing Tests because he was simply bored with it. “When I became the ODI captain for Pakistan, the board chairperson told me that I should also lead the team in Tests. I said no, I’m bored of it. The chairperson insisted, I said okay. But after one game with Australia last year, I realised I was bored again. That’s it, I said, I don’t have the temperament.”

Perhaps it is this attitude that could enable Pakistani cricket—and with it the nation’s morale—to claw out of depths to which it has sunk. The attack on the Lankan team bus in 2009 ensured that Pakistan wasn’t to be the destination of foreign cricket teams. Then three of its top players were banned for spot-fixing. And it isn’t simple to play cricket abroad even as your cities reel under terror attacks. “You are worried for your kids, they go to school,” says Afridi. “We all believe in Allah. We focus on our game and talk to our families on the phone and ask them to take care of themselves.”

He pauses and adds somberly, “That’s why the World Cup is important, to build everything back. The Cup means a lot for the team, for the country.” Here’s hoping cricket’s healing touch, and Afridi’s chutzpah, could mark a turnaround in Pakistan’s destiny.

Tags