Weighing In For Life

Malnutrition is a killer even today. In Thane district, a simple diet plan is saving toddlers.

- The authorities acknowledged the deaths were caused by malnutrition

- A programme for children under six and their mothers was launched through anganwadis

- Local produce like millets is used to provide them protein-rich meals

- The Infant Mortality Rate in 50 villages came down to 2.26 from 53 per 1,000 in a year

- The programme targeted pregnant women, mothers and children

- The broader plan must be to spread nutrition awareness among a generation of women

***

It's Madhya Pradesh that immediately needs to learn a few lessons from Thane. Four tribal districts here—Satna, Shivpuri, Khandwa and Sheopur—have seen 125 malnutrition deaths in the last five months. Annual mortality rates are at a high of 60-70 per 1,000 infants, and all for lack of enough nutrients. But like the Thane officials four years ago, the MP authorities are in denial. They attribute the deaths to pneumonia or diarrhoea, even go on to discount the malnutrition factor.

So what is the Thane formula? It's all about providing a simple, high nutritional value meal for mother and child. In the tribal belt here, they call the mixture lapsi—it's actually a paste of locally grown green millet, soaked, germinated, dried, roasted and mixed with peanuts and jaggery. This is mixed with milk and served to children below six and their mothers.

Around a year ago, over 33 per cent of the babies born in Jawhar and Mokhada were born severely underweight. Almost 85.8 per cent of the pregnant women had a body mass index (BMI) of less than 18, an indicator that they were malnourished. Today, lapsi has changed things. The infant mortality rate (IMR) in the two blocks—with close to 50 villages—is down to 2.26 in Jawhar (from 53 per 1,000) and 8 (from 54.66 per 1,000) in Mokhada.

Equally encouraging is the fact that local authorities readily acknowledge now that there is a malnutrition problem. And that despite the success there is much more work to be done. Dr Ramdas Marad of the Cottage Hospital in Jawhar is candid, "We are trying hard to tackle the cause of malnutrition. Factors like illiteracy of the parents, particularly the mothers, have to be addressed before we can really do something."

In clinical terms, malnutrition is divided into four categories. Grade I, or mild malnutrition is when the body weight of a person is between 70-80 per cent of the expected weight. Grade II represents moderate malnutrition—body weight is between 60-70 per cent of the average. In Grade III, the body weight is 50-60 per cent and in Grade IV it is down to 50 per cent of the average.

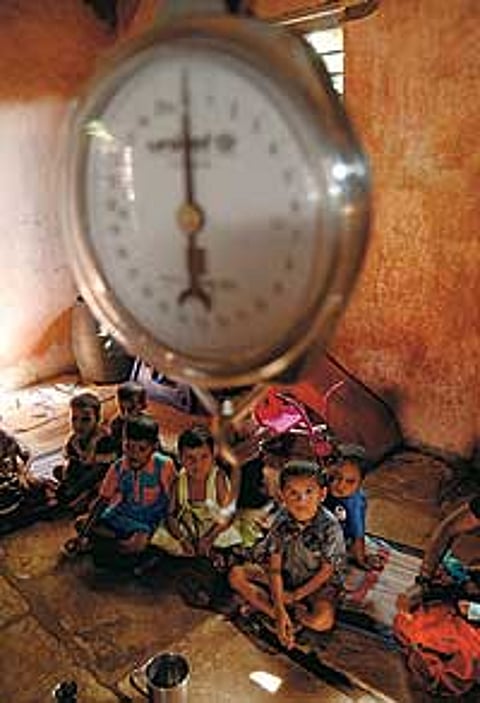

On balance: The weighing scale at the anganwadi in Hirve village |

To educate and provide expectant mothers with the right nutrition is critical here. Veena Rao, secretary, Development for Northeast Region, who initiated the drive against malnutrition a year ago during her CAPART stint, says, "The figures tell the story of how interventions done so far have focussed only on the weight of the child. It's important to address the issue as an inter-generational one, and look for cures to the ills that occur in successive generations of women. No single intervention can eradicate malnutrition."

She adds that the intervention package must be widely inter-sectoral (as in government departments involved) and must cover the entire life-cycle of women and children to create an impact within one generation by tackling the nutritional status of the three critical links—children, adolescent girls and women. "Only then can the benefits be sustainable enough to break the cycle and be passed on to the next generation. Policymakers have to make a choice between waiting for the benefits of growth to trickle down or just immediate intervention," says Rao.

In Thane this began with plugging the protein deficiency. Mixed with water and milk, the green millet mixture, lapsi, was the supplementary food given to underweight babies. The workers at the anganwadi or the local palnas (creches) were trained to give this mixture at regular intervals. The weight of the babies was monitored once in two months. Along with this adolescent girls were taught the importance of not marrying young, a practice widely prevalent here, and one that activists admit is unlikely to change immediately.

The Maharashtra government has also started child development centres (CDCs), where extreme cases of malnourishment are referred to for treatment. Still, not every story has a happy ending. Till September this year, three infants had died in Jawhar and Mokhada. One died due to hypothermia, the other was born to a mother who had already borne six children. Unfortunately, the CDCs can keep acutely malnourished children and their mothers for only 21 days. After that, they return home and usually regress. It is here that the battle has to be fought all over again.

The quiet transformation in Jawhar and Mokhada should be an eye-opener. It proves that initiatives involving the people at the grassroots level do produce results. But for that to happen, one needs authorities at the local level who have the commitment and the vision.

Tags