Midnight’s Orphans

In a house in old Delhi stay eight people, moored in the past. What do they dream about? A corner of a foreign field that’s forever Anglo-India.

Doris Louis, 83, deplores the foolishness of those who would call her ‘Anglo-Indian’. “I know who I am. I am Irish,” she says. She takes great pride in the fact that her great-grandson, despite having ‘Indian’ blood, has inherited an almost milky-white complexion—the colour of her and her father’s skin. Refusing to buy into post-Independence nomenclature, she says she was born in “Cawnpore”. “But it made no difference where I was born because India was Little Britain then. I think it was just wonderful growing up in those times, but those days will never come back,” she smiles fondly.

The eight Grant Govan dwellers complain of constant, needless, internecine bickering. But for once, 77-year-old Philomena Berkeley agrees with Doris, sharing her senescent wistfulness for the manifold pleasures of Anglo-India. Her face turns pink as she remembers dancing with British raf men in her early teens. Sitting beneath a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II that hangs on her bedroom wall, she says, “The British were trying to make the place more civilised.”

Before running a parking lot in Connaught Place, he was an all-weather trucker.

“The Indians taught the British a good lesson. They went back with their tail between their legs, but a leopard can't change its spots. Go to England today and you'll find you're still a blackie. It doesn't matter if you have blue eyes.”

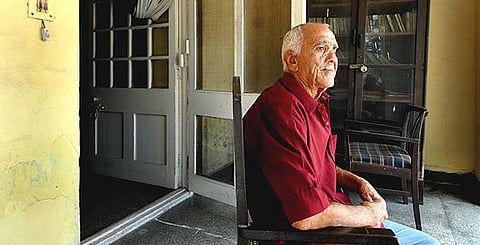

Tony Da’Silva, 74, thinks differently. The only man living at the Grant Govan Homes, and by his own account, one “persecuted” by the seven women with their “unfathomable” ways, he says he felt a thousand times more persecuted under the British. “I was only 11 then. I was on the Chowringhee crossing in Calcutta when I got kicked in the face for being a ‘bush monkey’,” which, he says, was a derogatory term commonly used for Indians. “All this talk of generosity is bullshit. The British were not kind to anyone.” So while Doris felt a tinge of sadness at hearing Nehru’s midnight “tryst with destiny” speech on the radio, Tony secretly exulted.

Worked as a nurse with the Assembly of God Hospital, Calcutta

“The British were trying to make Indians more comfortable, but there has been a misunderstanding always that they were hard on the Indians, that they were not treating them properly. They did so much good.”

However, he found himself part of a rapidly dwindling minority. The Anglo-Indian community halved from 3,00,000 in the two decades after independence, as many left India for better prospects. If you were to ask those living at the Grant Govan Homes to draw up their respective family trees, you’d find that the branches stretch to most corners of the world; Australia and England among the most frequent destinations.

Why did the Grant Govan eight stay on? The reasons range from the pragmatic to the romantic. Philomena was married to a man happy with an Indian job; Doris was loath to give up a queenly life, complete with servants; and though Tony had his Australian visa ready, he tore up his migration papers when his partner wondered if she would ever see him again. Flicking cigarette ash on to the floor, he explains, “We had lived together for 16 years. Matters of the heart and all.” Surprisingly, Philomena and Tony have no regrets for not having left. Philomena says, “When I go abroad, my nieces tell me I am a pukka Indian. ‘Your habits will never change Philomena, you will never learn’—that’s what they tell me, laughing at my English. So I like to go there on holiday, but after a bit I always want to come back to sunny India.”

Worked as an Indian army nurse and was posted in Calcutta and Ranchi

“After 1947, things have deteriorated so much more. There is so much hooliganism, no security for ladies, everything is so expensive, the traffic congestion makes you want to stay indoors forever. We've seen a better life.”

When she’s here, Philomena can often be found window-shopping in Lajpat Nagar. Tony, who likes to don stylish dark glasses, wanders around old and central Delhi for hours on end. Doris loves escaping to her daughter’s place in Dwarka at the earliest opportunity (she came into the home when things got difficult after her daughter, a widow, became sick). Others entertain themselves with dreary TV soap operas through the day. But as many of them willingly confess, it is the past rather than the present that holds them in thrall. Philomena talks at length about her Jewish grandparents who were thrown into German concentration camps during the Second World War. Tony details the turmoil of his mother, who was taken prisoner of war in Burma in the 1940s. Rita Koch, who doubles up as the home in-charge, looks disturbed as she remembers the events of a day in 1984 when she nearly lost her life after getting caught in the anti-Sikh riots. Another resident, Philomena Butterfield, giggles as she remembers sitting across the table from Sam Manekshaw and feeling weak in the knees.

R.E. Grant Govan was a British entrepreneur and the first ever president of the bcci. Like him, this curious octet can say they have contributed to national life in their own way. Butterfield served as a nurse in the Indian army, Doris was headmistress of three different schools in Punjab, and Tony was a truck driver who later gave up the highways to manage a parking lot outside Hanuman Mandir in Delhi’s Connaught Place. The Indian state can take some pride in the fact that despite their dislocations, they do feel, in some way, that they belong. As Tony concludes with some cheer, “So what if we are Anglo and like to waltz, tango and play tambola, we are Indians at the end of the day. I like Liverpool’s football, but I will always support East Bengal. No matter what.”

Tags