In the last three decades, the 30.2 km-long Gangotri glacier, the source of the Ganga, retreated at a rate three times as fast as it did during the earlier 200 years or so. According to the Geological Survey of India (GSI), it is now retreating at the rate of 23 metres a year. In the Tibetan plateau (the source of major Asian rivers like the Brahmaputra and the Indus), the greatest retreat of glaciers has occurred since the mid-1980s. Between 1950 and 1970, 53 per cent of glaciers here were receding. In 1990, 95 per cent were found to be receding!

In 1999, a report by the International Snow and Ice Commission created a stir when it predicted that most Himalayan glaciers will "vanish in the next 40 years". And that this will be preceded by huge flooding. But the scientific community is divided on this hypothesis. "If increase in glacier melt is to lead to flooding, then why, despite clear indications of glacier shrinkage, are the river discharges coming down?" asks Dr V.K. Raina, chairman of the government's Programme and Advisory Committee on Himalayanglaciers. Changing climate could be leading to increased river flows in other parts of the world but the Himalayas are different.The latest studies done by glaciologists at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG) point towards a far grimmer scenario. Says Dr J.T. Gergan, a senior glaciologist who, since 1997, has been studying the Dokriani glacier on the Bhagirathi basin, "There will never be any massive flooding from melting glaciers in the Himalayas. We are already in the period of reduced run-offs." Dr Gergan and his colleague Dr Renoj J. Thayyen discovered that discharge in the lower levels of the stream originating from the glacier reduced by more than 50 per cent from 1998 to 2004.

Why is it that despite more melting, run-offs from glacier catchments are down? Glaciers, explain Gergan and Thayyen, are not just receding from their snouts but are shrinking all around, even losing their thickness. They are also melting in the accumulation zone (see graphic) where earlier it would only collect snow. So the equilibrium line or the line dividing the accumulation zone from the melting zone is moving higher. "The overall warming of the glacier environment due to loss of glacier volume is affecting local weather patterns and causing rain to fall in altitudes where earlier only snow used to fall," says Thayyen. The snowline is going up each year. This has an adverse impact on the moisture storage capacity of the glacier catchment downstream, because with not enough snow cover or shorter durations of snow cover, enough moisture is not percolating into the catchment to recharge springs.

The result is lesser run-offs in the lean season from December to May. In a hot year, the situation turns worse. With a thinner blanket of snow on its surface, the glacier is unable to prevent its inner core (the hard ice frozen since centuries) from melting. Thus, when discharges from other sources in a river's catchment (like snow melt and underground springs) go down, the glacier's contribution to the river is going up. It's a vicious circle which, even though it's helping keep river flows somewhat stable in the present, spell trouble for the glaciers, which are losing more of their core each year. In other words, the melting of glaciers is helping to compensate the loss in flows from other sources and vice versa. This, says Thayyen, "is affecting the base flows (the flow during the lean season) of the rivers which have really gone down, because during this period the glacier cannot contribute much." As glaciers shrink further, the problem will aggravate, and smaller glaciers, more vulnerable to climate change, are already reflecting this.

High Water, Then Hell

The 33,000 sq km of Himalayan glacier area is receding faster than anywhere in the world. Our rivers will swell, then dry.

Approximately 60 to 70 per cent of the more than 200 glaciers in the Bhagirathi basin may be reduced to small patches of ice in less than 50 years from now. Only the larger ones like Gangotri might survive. The Dokriani glacier shrank 550 metres between 1962 and 1965. But from 1991 to 1995, it shrank 69.9 metres, its average annual rate of recession 17.4 metres. The Yamuna basin which is fed by 52 glaciers is already showing signs of distress. "That's why even in a year of good snow there is water shortage in Delhi," says Gergan. "There just isn't enough water in the river during the March to June period just before the monsoon as the base flows are down (see box)."

The WIHG study also stresses that the lower reaches of the rivers away from the catchment where many hydroelectric power stations are being planned or have already been constructed will be most affected by glacial changes. "Engineers will have to find ways to generate power from lesser water," says Dr Raina.

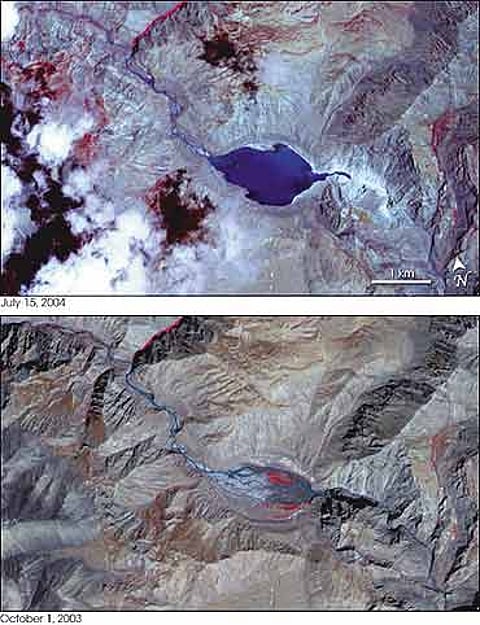

But flooding could be caused by the steadily increasing number of glacial lakes in the higher reaches.As glaciers retreat, they leave behind debris called moraines at their snout, which act as a dam for the melting snow to collect. Remote sensing agencies have noted an increase in the formation of theselakes. Though Pareechoo on the Sutlej is not a glacial lake, the manner in which it burst and flooded downstream areas last month is similar to the phenomenon called Glacial Lake Outburst Flow (GLOF). Last year, the Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University, in association with UNEP and the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), Kathmandu, conducted a detailed assessment of glacial lakes of Himachal Pradesh. Says scientist Dr R.M. Bhagat, who conducted the study, "We found a surprisingly large number of glacial lakes, 229 of them. Of these, 22 spread in all the major river basins of Sutlej, Ravi, Beas and Chenab have been identified as potentially dangerous." There have been a number of GLOFs in the last few decades, in the upper altitudes, which affected local communities. Some of the recent flash floods in the Sutlej and the Beas, researchers feel, could have been due to GLOFs. As these lakes get bigger, people in more populated downstream areas will be impacted. The Pareechoo lake burst led to losses worth Rs 800 crore.

Scientists and glaciologists in India are hampered by inadequate data, as little research has been done on the subject. Now that the impact is beginning to be felt and international agencies too have sounded the alarm, there is a mad scramble to work out different theories. However, what may be happening in the Alpine mountains of Europe need not necessarily happen in the Himalayas, because the Himalayas get snow during the monsoons. "All these years, this was a relatively neglected issue. We lack long years of data and research across different climate zones in the Himalayas," says Thayyen. "Now it's become a knowledge game between the developed countries (who have the database) and developing ones (who lack it) because of which there is a tendency among international agencies to force their point of view and influence water resources management strategies at the highest level on the basis of studies reported from other mountain regions of the world. The need of the hour is to strengthen our knowledge base on hydrology and hydrometeorology of mountain catchments."

Glaciers, always remote and inaccessible, have defied comprehensive studies. Today, ISRO's satellites map glaciers, but these aren't too accurate due to the peculiar geography of the Himalayas, with shadows and steep valleys. In 2002, the Centre's Department of Science and Technology told Parliament that on the basis of the recommendations of the Parliamentary Standing Committee of Science and Technology, it has decided to set up a National Centre for Field Operations and Research on Himalayan Glaciology, to exclusively study the problem of melting glaciers and their impact on the country. The proposal is still on paper.

For the moment, it's a mixture of equal parts confusion and apprehension. Forces much beyond human control are at work. Glaciers have their own cycles of advance and retreat which last about 10,000 years or so. But this time the recession has been dramatically accelerated by man-made factors like greenhouse gases, degradation of tree cover, and misuse of natural resources, like overdrawing underground water. And the fate of billions of people hangs in balance.

Tags