A Bend To The South

Not just natives, even north Indians are opting for the peace and prosperity of the southern metros

Gupta isn't the only one to have chosen to forsake the metros of the north and opt for the peace of the south. Some distance away, in Kochi, resides S.P. Singh and his family. A former vice-president of Toshiba Anand, Singh moved to Kochi from Delhi in 1973 and now, 34 years later, he marvels at how the city has developed. "Kochi is fast becoming another Singapore," he exults, and now he would not consider living anywhere else.

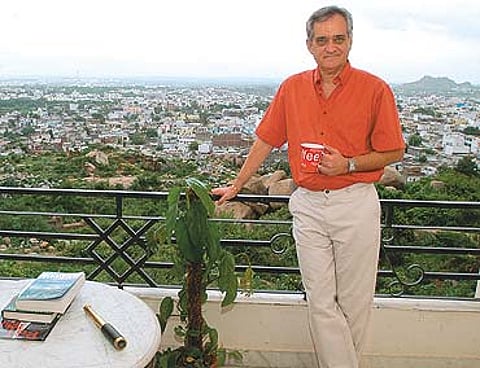

Equally enthusiastic are those Keralites who have spent their working lives outside south India but have chosen to come back home to spend their retirement years. Among them is T.P. Sreenivasan, a former ambassador who chose to return home to Kochi after 40 years in Delhi, New York, Vienna and Nairobi. Eschewing the seminar circuits and think-tanks of Delhi, the usual refuge of retired Indian diplomats, Sreenivasan finds Kochi offers all the amenities of a metro like Delhi, but mercifully "without the pollution, traffic snarls, extremes of climate and high cost of living". (Well, we reserve comments on the traffic in Kochi, but affirm the rest.)

It's not just Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram that are being rediscovered by eager north Indians, or by prodigal sons and daughters returning home to the south after many years. Scores of people who have moved to south India from other parts of the country lyrically extol the quality of life in Hyderabad, Chennai and Bangalore, even as they recall the rudeness and aggression, the congestion and pollution, the greedy landlords and leering roadside Romeos, the long hours spent commuting to work, the fear of terrorist violence and crime that were part of their daily lives in cities like Delhi or Mumbai. The southern cities, they find, have an exciting new entrepreneurial buzz, but retain the peacable qualities that always set them apart from their northern counterparts.

His wife Indrani Das, who works with a web content development company and is from Calcutta, agrees, and especially appreciates the premium on knowledge, which makes the work environment in Hyderabad stimulating. And congenial as well, adds Anvar. "I always believe," he says, "that rice-eating societies are more peacable than wheat-eating ones. As such, they have a more consensual style of working, which makes them more effective organisation workers."

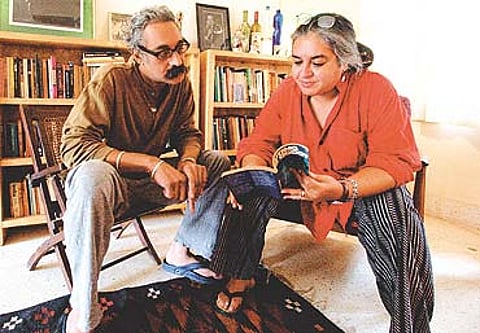

For Jayanti and Javed Alam, in contrast, it's old Hyderabad that's appealing. "It's the tehzeeb of the city, its rich culture in Urdu and Telugu," says Jayanti," in contrast with the rude, aggressive, self-centred behaviour one finds in Delhi." The Alams lived in Shimla and Delhi, he as a professor of political science, and she as a schoolteacher, before moving to Hyderabad in 2000, where Javed had relatives. "Everything here is better," says Jayanti. "The climate is pleasant except for two months in the year, the rents are lower, food is cheaper, so is eating out. People are more friendly, they have time for each other. And, most important, it's not dangerous for women. Delhi is a terrible place forwomen--I'm 63, but in Delhi any woman from 7 to 70 feels vulnerable to sexual crimes."

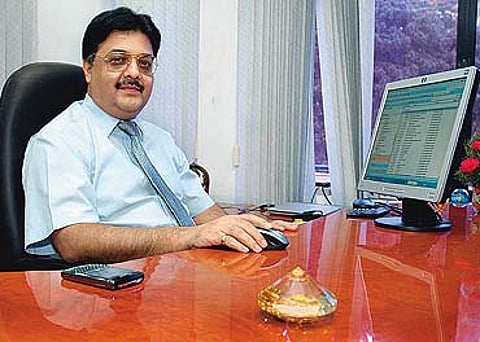

It was work that brought Amitabh and Anuradha Chandra to Hyderabad from Chandigarh, but it is the culture of the city that has made them decide to stay here forever. The couple moved in 2002 when Amitabh got a job as theCEO of a call centre. He soon moved on to start a firm that offers satellite-based education programmes and corporate training modules. Now they have their own flat and plan to settle here, seduced by the pleasant climate, the good schools for their children, and the thriving environment for business. Compared to Hyderabad, says Amitabh, "Chandigarh is like an overgrown village. This is a great place to bring up our children."

Gurgaon, home to gleaming MNC offices and malls, too was a village on anabolic steroids and held few charms for advertising professionals Ravi Ganapathy, 38, and his wife, Deepa, 35, who gave up its condominium culture two months ago for a less perpendicular home in their hometown, Chennai. They tick off the reasons for returning: lack of public transport in Gurgaon, a safe and secure environment, especially for women, and the exorbitant cost of living. They also missed Marina beach. "While Gurgaon appears swank and glossy, there are pockets of it that make you feel like you are back in1947--it needs to do a lot more to become the millennium city it claims to be. Chennai is a wonderful mix of the old and the new," says Deepa. "And its airport and railway station are far more impressive than any I have seen in India."

Clinical nutritionist Ranjani and her entrepreneur husband Harish call themselves pucca Mumbaikars, but are steadily morphing into Chennai fans eleven months into their stint in the city. When work brought them here, they thought they were moving, to a "hot, conservative city, with nothing to do", confesses Harish sheepishly. Instead, they found shops that stay open late, wide choices in entertainment and food,and--yes--neighbourhoods with a cosmopolitan feel. "It's no longer a staid, orthodox and judgemental place," says Ranjani. "Chennai now has the feel of a big metro, like Mumbai." For marketing professional Sachin Khurana, 32, and his wife Shweta, who moved from Delhi a year ago, Chennai means "a much more relaxed and organised pace of life, and an end to the commuting nightmare." He does not find the city inimical tooutsiders--not in his world, at least: "In an MNC, the work culture is pretty much the same, in Delhi or in Chennai "

Or Bangalore, we might add. It is a second stint in the city for Arshia Sattar, a teacher and translator. Having lived here in the early '90s, she moved back here in 2005 from Pune to coordinate the annual theatre festival at the Ranga Shankara theatre. She finds the difference stark. "Despite the rise of linguistic nationalism, Bangalore seems to be becoming a city now," she says. "There are tensions, diversity issues and chauvinisms, but Bangalore seems to have understood that outsiders are here to stay. There are jobs here for young people like there are in no other part of the country. It's certainly a very young city visually, you see young people everywhere." The biggest draw for her is the cultural vitality of the city. "The Bangalore arts community isyoung--not big on money, but big on ideas and courage. And a fair amount of it is constituted by people who are not native to the city, which means that the city welcomes new practitioners and thinkers."

People in Bangalore are so much more content with their lives and lifestyles than in Bombay or Delhi, says Sai: "They are not as obsessed with racing ahead of each other. In Bombay, if you stand still for a moment, you're losing the race. And in Delhi, everyone's playing to thegallery--it's corrupt in that way, and pretentious."

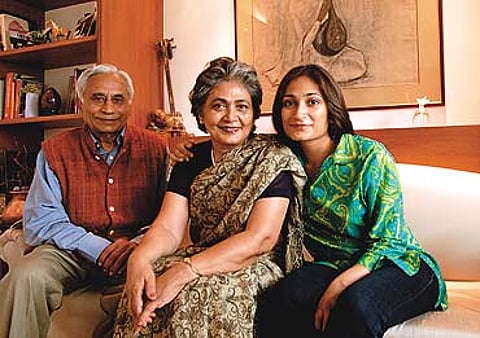

Ask former diplomat C.V. Ranganathan who spent 12 years of retired life in Delhi having served as ambassador in China and France. Finding Delhi's "harsh climate, the threatening environment for women" too hard to take, he, himself a native of Chennai, and his Malayalee wife Vijaya decided to strike roots in Bangalore. "The city's cosmopolitan nature is reflected in its diverse cultural life. And itsrestaurants--you can get very good Vietnamese, Japanese, Korean and Italian food here," he says. "And amidst all the multiplexes and shopping centres coming up, you find pockets with the old-time Bangalore ambience. That adds to the city's charm."

However, it's not as though all is gung-ho down south. Bangalore may have grown up, but Arshia is still sometimes shocked to realise how much she is perceived as an outsider. Nor are southern cities by any means immune to the problems plaguing other rapidly expanding Indiancities--be it the crumbling infrastructure or growing traffic. Moral policing is an irritant, in both Bangalore and Chennai; cosmopolitanism has itslimits--northerners settling in Chennai have to contend with house-owners insisting on vegetarian tenants; schools could be better. But all in all, when it comes to comfort levels, the compass is pointing due south.

By Team Outlook with Raghu Karnad, Madhavi Tata, Sudha G. Tilak and John Mary

Tags