Whatever Kiren Rijiju, the minister of state for home, was doing last April, he certainly wasn’t watching Telugu low-budget parody blockbuster Hrudaya Kaleyam. The film’s hero, Sampoornesh, rises from his funeral pyre to lynch villain Black Mambo with a double-headed battle axe. The level of gore in such movies—films from Madurai are another example—would make Hannibal Lecter blush. Were this film one’s sole portal for information on Andhra Pradesh (or for that matter Telangana) denizens, the natural presumption would be that they engage in brutal and sickeningly gory fights unto death, armed with cardboard cutout weapons.

When A Bad Rep Precedes Reality

That has been the north’s problem when it comes to perception of it being more crime-prone. Read the numbers again. It’s no better in the south.

Strangely, that’s exactly the sort of assumption Rijiju made last month about north Indians when he painted them as people who take “pride and joy” in breaking rules. He attributed the remark to former Delhi lieutenant governor Tejinder Khanna but that hardly helped matters. Like Khanna, Rijiju had to eat his words, for nobody believes any longer that India’s north is, somehow, shadier than its topographical other, the south of India.

Even former top cops who have seen their share of cross-country blood agree that India’s four regions—the north, south, east and west—are mere geographical entities, making no statement about the intrinsic worth or nature of its many residents. Retired supercop Julio Ribeiro says, “If any assertion of this nature has to be made, it must be backed with empirical evidence. There is no such evidence that can be relied upon, so that leaves only a gut feeling—that’s where this kind of assertion about the north comes from.”

Seen from Rijiju’s eyes, the two giant regions of India watch each other suspiciously over the Vindhya-tops. It is likely, however, that east India didn’t enter the minister’s mind as a candidate for the most lawless in his assessment. What’s got the experts in knots is that the stereotype persists; a few harsh words in Delhi, an elbow pushed in Chandigarh or a queue jumped in Ludhiana do not a north Indian criminal make, they say.

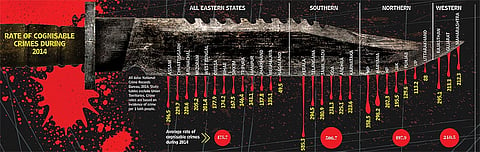

One reason why some may still ‘feel’ that the north is more lawless than the south is that they just haven’t read the crime numbers lately. They would find that it’s Kerala that’s filled with “law-breakers”, going by the National Crime Records Bureau data released earlier this year (see graphic). With just over 585 cognisable crimes per 1 lakh people in 2014, prosperous Kerala easily leaves poor Madhya Pradesh—the ‘Ma’ in BiMaRU—trailing with 358. Five of the top ten states in terms of the cognisable crime rate are in the south. The other five are scattered across the country.

“South India has a higher crime rate than north but the impression is that the north is more criminal,” says Dr B.N. Chattoraj, professor of criminology at the LNJN National Institute of Criminology and Forensic Science, Delhi. “That’s because there are more sexual offences in the north. Even this is just an impression. Delhi is called the ‘rape capital’ but it is not as if all girls are raped in Delhi—far from it.”

Looking at NCRB data afresh, and from a north-south perspective, Chattoraj finds that the average crime rate in north India is 248.3 and that in the south substantially higher, at 276.7 for every one lakh people. This estimate includes Himachal Pradesh, J&K, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, MP, Uttarakhand, Delhi and Chandigarh in the north; Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Lakshadweep and Pondicherry are counted in the south.

“We can no longer draw that old lawless versus lawful distinction between south and north India,” says Raman Mahadevan, a business historian. “I don’t think it is fair, all of India is blending into one now.” A key reason, he believes, is rapid urbanisation. This has made, for many crimes such as robbery, dacoity, theft and so on, south India as natural a home as any part of India. It isn’t surprising, then, that it’s Maharashtra that tops the dacoity and robbery charts in 2014, according to NCRB.

New money, experts argue, unfailingly mints a middle class, and crimes, sure as rain, follow in their wake. “Kerala, for instance, seems to be developing new types of crimes thanks to new money sloshing around,” says Mahadevan. “In Tamil Nadu, the social mismatch between the rich and the poor is not being addressed adequately. There is a growing impression, which I get from newspapers, that things are not as calm as they may appear in statistics. I notice crimes such as chain-snatching, ATM thefts more often.”

South Indian Criminals. Did You Say? Karim Lala, founder of Indian mafia; Varadarajan Mudaliar, inspirer of ‘Nayakan’, Mumbai gangster Ravi Pujari, sandalwood smuggler Veerappan; Chennai dons Auto Shanker and Haji Mastan

Sure, many more in the north are struggling to put two square meals together, but it’s not as though the south has it all sorted out. There are as many shopping malls creeping up on unsuspecting small-town aspirational classes in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh or Telangana as anywhere else, creating as many tensions. If crimes are the result of a struggle over resources and aspirations, south India is hardly better off.

***

What remains of the old north-south divide, many social scientists, criminologists and legal experts feel, is just “a gut feeling” about a lawless north. “Rijiju is confused,” says ex-cop Ved Marwah, a former governor of Manipur, Mizoram and Jharkhand. “He is confusing crime with indiscipline. Organised crime, after all, has roots in Mumbai and there’s not so much of it in the north. In the northeast, you have a different situation, where extortion is almost a home industry. Delhi, by those standards of south and northeast, is a much safer city. There is hardly any extortion here.”

Criminologists say they are concerned about the persistent assessment of north India as anarchic, especially in comparison to the south. Maxwell Pereira, a former joint police commissioner in Delhi, says that 30 years ago he was felicitated by seven Delhi gurudwaras for saving Sikhs during the 1984 riots. “Truth is, during those riots I saw so-called aggressive north Indians become victims of violence,” he says. What then feeds the stereotype of safe south India and unsafe north?

“South is seen as less violent, but I think this is only a stereotypical understanding of the north,” affirms social scientist Suhas Palshikar. He says every part of India has a different pattern of violence rather than less or more of it, and the south is only seen as less violent once the north has been branded violent. And, right across India, a culture of violence is likely to grow, he feels. “A macho culture upheld and perpetrated by commercialisation—in fact reification of all persons and relations—strengthens inclination toward violence,” he says.

Perhaps because the media is largely based out of NCR, the north gets larger play. So, Nirbhaya’s case was covered extensively, but the Shakti Mills crime, though reported in detail, attracted lesser attention. It is easy to talk up lawbreaking in Noida, Gurgaon or Delhi where big media is located. This, in turn, feeds the stereotype on where crimes originate. Akhlaq’s killing aroused the outrage it did partly because Dadri is next to Delhi, but Pune techie Mohsin Shaikh’s murder last June could not provoke similar reaction.

The closer one is to a crime scene, the worse it can seem. There are other factors at play. “In Tamil Nadu, the crime rate reflects who is politically powerful,” says Dr M. Srinivasan, head, department of criminology, University of Madras. The AIADMK, he says, is known to dislike wild swings in crime rates. “Therefore, the police there will not immediately register cases. They tend to wait, collect evidence, see if they have a case. So, in Tamil Nadu the crime rate doesn’t officially increase but is that really the case?”

Srinivasan, like many in his field, believes that the official crime statistics do justice neither to the victims nor help address the stereotypes. The crude north vs south debate doesn’t account for sub-regional variations in crime, which shows Uttarakhand has the second lowest crime rate, next only to Nagaland. Similarly, the “dangerous north” stereotype masks the everyday lawlessness in the south. “We end up believing that the north is more violent but the south is violent in different ways,” says Abdul Shaban, a professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. “In Mumbai, anybody from the north gets called a ‘Bihari’. They attribute characteristics accordingly, but incorrectly,” he says.

Under this stereotype, the sight of Chhota Rajan (Mumbai-born) being brought home in chains doesn’t trigger fears of a “lawless” south. Similarly, have you heard of anyone saying that Dawood Ibrahim (Ratnagiri, Maharashtra-born), Varadarajan Mudaliar (the Madras-born gangster who inspired the film Nayakan), serial killer Auto Shankar, also from Chennai, or Yusuf Patel, Haji Mastan (born in Ramanathapura, Tamil Nadu), are “south Indians”? Or ever heard anybody denounce ‘King’ Veerappan, the sandalwood smuggler, as a south Indian?

Malayalam writer N.S. Madhavan finds a kind of lawlessness in the “lumpen culture” on the streets in some areas of Kerala—the key southern state for lawlessness. “People are swayed by this culture, especially when it comes with the so-called glamour of liquor and drugs,” he says. Crimes in Kerala are more white-collar, say both Madhavan and Srinivasan, and both feel it is impossible to derive a state psychology based on the north-south divide. “Aren’t white-collar crimes always hidden?” asks Srinivasan.

***

India’s dominant narratives are built around caste and gender—one oppressive by nature, the other by practice. A Bihari immigrant in Gujarat may further accentuate conservative Gujarati culture. “Gujaratis are great wealth creators but weak at using it for social good. The south is better at it but in terms of gender one wonders how much of the old matrilineal system of Kerala still survives,” says TISS’s Shaban.

He doesn’t see the north acting independently on crimes either. He locates India’s “wealth generators” in an industrial belt running from Maharashtrian cities, cutting across Gujarat and parts of Rajasthan to end in Amritsar, Punjab. Workers in these regions, he says, are migrants from the east. “The worker’s incomes wind back in their home towns of Patna or Lucknow, where it inflates the economy. It gives their families muscle and money power, further perpetuating feudal caste relations,” he says.

In general, however, everyone agrees generalisations are dangerous. Ribeiro says that even in the most fraught situations, such as the ’80s, when he was putting down a Sikh rebellion in parts of Punjab, he made no such inference about its people. “Terrorism,” he says, “is another kettle of fish,” incomparable with crimes in general. “From what I experienced in Punjab, normal, everyday crimes were not such a big issue,” he says. Punjab had terrorism, the northeast states had insurgency and there was violent Naxalism in other regions. “The south perhaps had a little less of such problems. That doesn’t indicate any more or less propensity to crime,” he says.

“It’s ridiculous how we, without applying our minds, use statistics,” says Pereira. While posted in Sikkim, he often heard it was a “crime-free state”. Initially, other than the occasional drunken brawl, this seemed true. Then he discovered traditional village councils were sorting out even murders. “I got people to start registering FIRs and the situation reversed dramatically. It was as if all crimes began in Sikkim after Maxwell Pereira had come,” he says.

Crime stats, therefore, the biggest source of north India-bashing other than reports of rapes in Delhi, are not to be trusted. There is under-reporting, police refusal to register cases and misreporting. As Srinivasan says, “We don’t believe these crime statistics. We want to go beyond this data.” Once, while researching crime trends, Srinivasan saw NCRB data showing a lower rape rate in Bihar than in Tamil Nadu. No one could explain why. “I believe the official rape rate is higher in Delhi, like the official crime rate in Kerala, due to reporting behaviour—not actual occurrence,” he says.

Truth be told, crime stats and sweeping stereotypes are strange bedfellows. The real crime is perpetuating myths.

***

The Crime Graph A Bloody Trail In The Country

India’s most literate state is the most crime-prone too, it would seem. The national capital, of course, remains the most notorious in terms of numbers, but is that a function of better reporting of crime than away from the centre of media industry?

Union Territories (COG Crime Rate) Delhi: 767.4, Pondicherry: 225, Chandigarh: 192.2, A&N Islands: 138.9, Lakshadweep: 102.5, Daman & Diu: 75.4, D&N Haveli: 68.1

Top 5 States For Each Crime

Murder

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Meghalaya

- Jharkhand

- Assam

- Haryana

Spl Local Laws

- Uttarakhand

- Kerala

- Chhattisgarh

- Uttar Pradesh

- Gujarat

Law And Order

- Kerala

- Sikkim

- Bihar

- J&K

- Assam

Econ Crime Rate

- Rajasthan

- Telangana

- Goa

- Kerala

- Assam

Rape

- Madhya Pradesh

- Rajasthan

- Uttar Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Assam

Road Rage

- Kerala

- Tamil Nadu

- Madhya Pradesh

- Karnataka

- Gujarat

Robbery

- Maharashtra

- Uttar Pradesh

- Karnataka

- Madhya Pradesh

- Tamil Nadu

Cheating

- Rajasthan

- Uttar Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Telangana

- Karnataka

Related story The Blood Meridian

Tags