The Pecking Order Of Law

He'd chase the law after the crime. That's where a BMW boy differs from a bus driver.

- Jan 10, 1999: Six people, three of them policemen, are killed when a speeding BMW car driven by Sanjeev Nanda runs them over at a police barricade in Delhi's Lodhi Colony late at night. The car speeds away, leaving an oil trail that leads police to a house in nearby Golf Links, where the car has been washed of bloodstains and fingerprints.

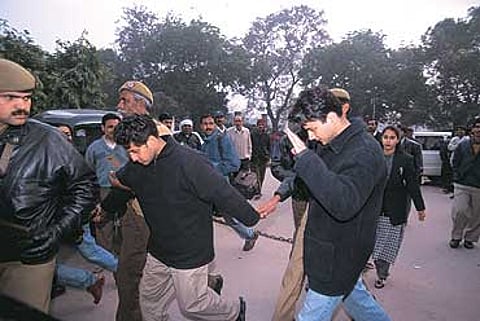

- Jan 11, 1999: Nanda and his friends Manik Kapoor and Siddharth Gupta, who were in the car, arrested.

- Jan 14, 1999: Key witness Sunil Kulkarni records statement.

- April 1999: Police formally charge the three accused, and three others, under IPC Sections 304 (culpable homicide not amounting to murder), 308 (attempt to commit culpable homicide not amounting to murder), 201 (destruction of evidence).

- July 1999: The Delhi High Court orders Nandas to pay compensation of Rs 65 lakh to victims' families. Next month, the high court acquits Siddharth.

- September 1999: Prosecution drops Kulkarni as witness.

- May 14, 2007: Kulkarni, now appearing as a court witness, identifies Nanda as one of the occupants of the BMW. He, however, says he did not see him driving.

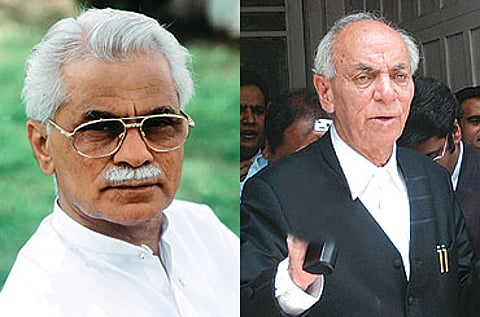

- May 30, 2007: An NDTV sting operation shows defence counsel R.K. Anand and prosecutor I.A. Khan colluding to influence witness Kulkarni. Khan asked to withdraw as prosecutor. The high court issues contempt notices to both lawyers.

- August 2008: Prosecution and defence conclude final arguments. The HC holds Anand and Khan guilty of contempt and bars them from appearing in court for 4 months.

- Sept 2, 2008: Nanda found guilty of "culpable homicide not amounting to murder". Evidence against him includes his blood on BMW steering wheel, consistent with injury on his face. Three others, including businessman Rajeev Gupta, convicted for destruction of evidence, co-accused Manik Kapoor acquitted.

***

The sympathy, if sympathy it is, is bizarrely misplaced. A wantonly negligent truck driver fleeing a mangled corpse and a wrathful crowd runs in the knowledge that if he is caught, he will be at the unmediated mercy, not just of the crowd, but of the criminal justice system. More often than not, there will be no clever lawyers to save him from police and prison excesses, to secure breaks for him from prison life by transporting him to hospital on the plea of claimed illnesses, to get a fair deal for him in court. That does not mean it is OK for him to run away, or not be punished for his crime. But should he be spoken of in the same breath as a well-educated young man who runs away from a deserted late-night winter street strewn with the bodies of his victims, some dead, others writhing in pain? Who flees responsibility when a single phone call by him could summon prompt medical attention for them, and save lives, were there any to be saved? Who flees the law despite the knowledge that his family can engage the country's best lawyers to defend him in court?

Sanjeev was dazed and drunk. However, he was not so drunk that he could not drive his way to a safe haven—or what he thought was one—where he hid while his car was hosed down to destroy evidence. Along with the likes of Salman Khan and Neel Chatterjee (the top executive reported, ironically, to be an authority on corporate social responsibility), he belongs to a pantheon of well-placed citizens who could have expiated for the original sin of drunken or dangerous driving by showing spontaneous humanity to their victims, but drove away to escape the tentacles of the law.

That the "BMW case", as it came to be called, received relentless media attention is a sore point for the defence, and a justifiable matter of pride for the media. There is no doubt that Sanjeev's identity, as the grandson of a naval chief and the son of a rich arms dealer, and the killer car's exalted status as a BMW rather than a modest Maruti 800, influenced the level of attention. This—grossly unfair though it is to the victims of less publicised crimes—is how it is, when those with status are the perpetrators of crimes. But it is also exactly this way when the rich and famous are the victims of crimes. It's just that you don't hear their lawyers complaining when break-ins on Prithviraj Road become breaking news, while rape in Jahangirpuri goes virtually unnoticed.

However, the case also attracted attention for reasons other than Sanjeev's status. It attracted attention for the horror of six lives snuffed out gruesomely, with bodies dragged by the speeding car; for the tracking down, with the help of an oil trail, of the killer car and its driver by a cop who showed rare tenacity and drive. But above all, it attracted attention for the twists and turns it took as Sanjeev's family pulled out all the stops to save the young man from the consequences of his actions.

Just as the BMW car morphed into a truck in a hostile witness's testimony, the BMW case also transformed itself, over nearly a decade, from a road accident to a metaphor for justice subverted with money power. As judge Vinod Kumar put it incisively on September 2, it drew attention to a situation in which "wealthy and highly placed persons are able to thwart the entire course of justice, and thereafter at the end, claim benefit of doubt as a matter of right." Equating it with everyday hit-and-runs is like dismissing the stand-off in Singur as just another property dispute.

As the Nandas gave out legally sanctioned blood money, in a calibrated gesture of belated concern for the victims of the tragedy, a murky parallel track of activity saw testimonies being doctored and witnesses turning hostile, one after another. As black-robed lawyers squared off in the courtroom, representing prosecution and defence, in another murky parallel track they mocked their adversarial courtroom positions by colluding with the only witness who did not turn hostile.

We may endlessly debate the ethics of sting operations, but no one can deny they have left us with indelible images of the way we are. Just as the frozen frame of Bangaru Laxman shoving notes into a drawer became the ultimate visual image of political corruption, the damning recorded conversations of the maverick BMW case witness Sunil Kulkarni with public prosecutor I.U. Khan and defence lawyer R.K. Anand summed up the subversion of the criminal justice system.

Against this background, the defence's claim that the media interfered with the administration of justice and its highlighting of the Nanda family's "contributions to the economy" (unfortunate phrase!) are redolent with unintended irony.

Tucked away in the impedimenta of the BMW case are not just one or two, but many shaming stories. A sad and telling one, even if far less consequential than the revelations of the sting, is the cameo role essayed by Sanjeev's grandmother. Last year, as the first defence witness in the case, she testified that her grandson was innocent. To make her point, she even invoked the sanctity of the grandmother-grandson relationship, telling the judge, "He never lies to me". To protect your young is an age-old instinct, an understandable one. And yet, a grey-haired granny is a powerful image of ordinary decency and morality. It debases not just a family but a society when she defends the indefensible.

Tags