When it comes to the dark arts of Hindu vote consolidation, though, men like him, prepping the crowds before Varun Gandhi's meetings in Pilibhit, do not need lessons. They stand on stages draped in saffron and flirt dangerously with the election code—more dangerously than Varun, with the spotlight trained on him, clearly wants to right now. By the time the large young man arrives in a jeep kicking up dust, the Jai Shri Rams are rolling easily off tongues, the kamal ka phools are being obscured by dancing triangular VHP flags, the tough-looking fellows in T-shirts, snazzy dark glasses and saffron scarves who were earlier zipping around on motorbikes, are milling around in an orchestrated frenzy. Party workers twice Varun's age are getting ready to touch his feet, and the audience is waiting to listen to him.

Frankly, as speakers go, he isn't quite Saffron Idol. This is not the bravura performance of a Vajpayee or even the compellingly poisonous discourse of a Sadhvi Rithambara; it is an ambitious youth trying out oratory, with some coaching, in a language for which he has no feeling. He starts out with a flurry of drawn-out greetings in laboured Sanskritised Hindi (paramadarniya matgan, paramadarniya netagan...), but descends rather quickly into violent imagery ("Yeh sarkar mujhe phansi laga deti", "meri gardan kat jaye, mein aap ki gardan jhukne nahin dunga", "goli khaane ko tayyar hoon"). There's a lot of "izzat" and "atmasamman" and "rashtrabhakti" tossed around, along with a few clumsy compliments for Pilibhit, and the mandatory references to the 20 days (though you would think it was 20 years) in Etah jail, but it's all rather empty. As Narendra Modi could have easily demonstrated, there are more scintillating ways of reaping the benefits of notoriety without risking a lauki-eating stint in jail.

But in the end, it doesn't matter. The saffron family has plenty of paan shop propagandists to supply rhetorical fluency. What Varun supplies is the idea of Varun: fair, strapping, pedigreed, headline-making, helicopter-riding Varun; young, purposeful, 'Hindu-minded' Varun, vengefully punished by Behenji. (Even those who don't endorse the viciously anti-Muslim speeches he made in March to attract Hindu votes think she overdid it.) While being a Gandhi will probably hamper Varun in his ascent up the BJP ladder, it's not so in Pilibhit. Retorts Prakash Kashyap, a farmer travelling on a village road in a crowded rickshaw, when I quiz him about Varun's inexperience: "Think of the sacrifices his dadi, uncle, father have made for this country. " And then, whether it's a college student fighting mofussil boredom or a labourer fighting desperate poverty, there is that poignant flicker of hope you always encounter in the so-called VIP constituencies—in the alleged life-transforming abilities of "hi-fi" candidates.

What Varun needs to do to keep these strands together until May 13 (voting day here) is to look glamourous, dynamic, hyper-nationalistic and deferential, all at the same time. So far, he appears to be doing nicely. At one meeting after another, as the 29-year-old soaks up chants of "bhavi saansad" and "bhavi mukhyamantri" (future MP, future CM) his face also swivels around the stage, looking for workers he can identify, and praise. Though clearly wary of the media, he could teach mummy Maneka a lesson in calculated cordiality ("I am sorry, ma'am," he says, "I'm not giving any interviews these days." And then, with a smile: "I saw you at Aonla.") Local VHP chief Deepak Agarwal is acutely aware of the comparison. Maneka, the sitting MP, always kept him at arm's length, he confesses; Varun, whom he trekked to Etah jail to visit, is a delight.

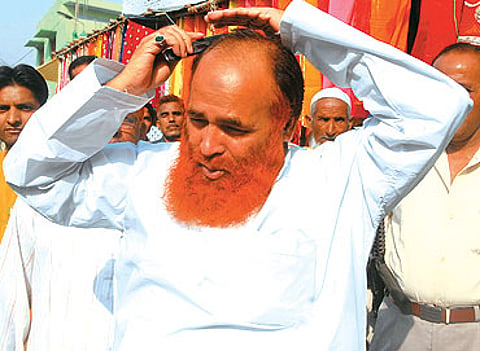

It's not hard to see why he thinks so. Pilibhit is a deceptively placid place, where you run into Hindus and Muslims sharing a rickshaw or sitting in the same teashop. But in a constituency where the Muslim vote is substantial—about three-and-a-half lakhs—and the Hindu vote over twice as much, Varun's nastiness seems to be driving the desired wedge. In a teashop in Jehanabad kasba, a multi-caste group of Hindus, among them Brahmins, banias and kurmis, make no secret of being unabashed Varun fans. The lone Muslim shopkeeper sipping his tea stays silent, clearly not wanting to start a fight. A kilometre or so away, at a mela adjoining a dargah, Muslims are not silent. "Varun dushman hai," says kabab-seller Mohammed Sharif sullenly. His customers all agree.