The Grim Reaper

Vidarbha's farmers are a broken lot. The rains, the state all failed them.

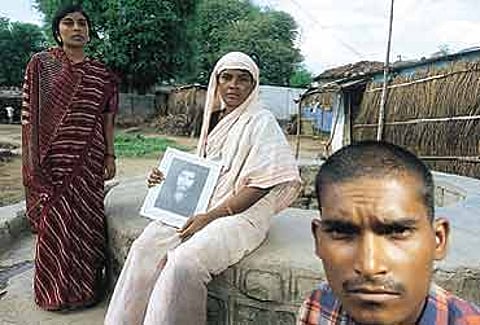

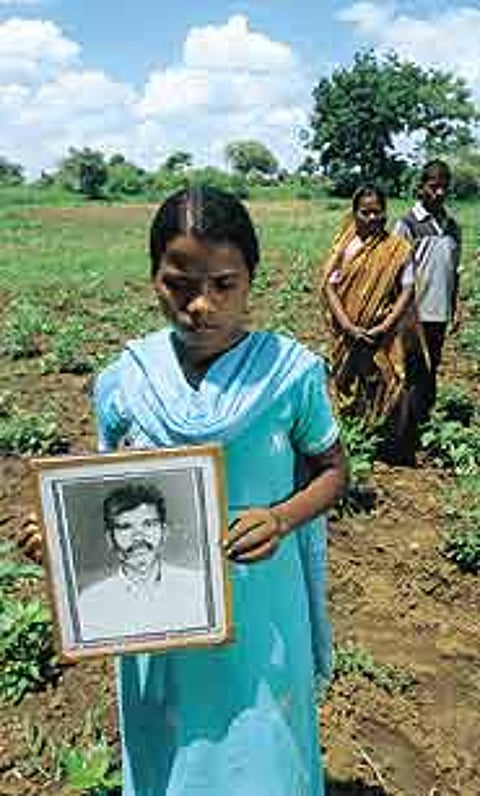

Jitruji Sukhdevrao Kinnake's house in Wadhona Bazar village, Yavatmal, is freshly painted. Barely a month back, the 45-year-old Kinnake had celebrated the weddings of his daughter and son. Now, on his 13th day shraadh ceremony, the paint and pandal are a cruel irony. Kinnake apparently had taken loans from everywhere possible. The weddings only piled it on further, still he borrowed some more and sowed cotton and soya for the second time in early July. The rains failed again. Kinnake decided that suicide was the only way out.

Yavatmal, the cotton crucible of Maharashtra till a few years ago, is now resigned to stories of deep rural distress—and suicides. Across the region, Yavatmal, Amravati, Akola, Wardha, Washim, Buldhana and Bhandara districts that make up chronically drought-prone Vidarbha, it's the same story. The spate of suicides began in late June, a month later nearly 50 farmers had taken their lives. Most were small farmers. They had pawned their houses, cattle, some even their wives' mangalsutra to borrow money but finally it was the vanishing rains that broke their spirit. Since 2001, 340 farmers have committed suicide in this region.

On July 20, six weeks after the current spate began, CM Sushilkumar Shinde and his deputy Vijaysinh Mohite Patil visited Amravati and Nagpur to get a first-hand perspective. They didn't make time for a single suicide-affected family nor did they visit the affected villages. The two men met officials in Nagpur, after which the CM reluctantly admitted to the local press: "I don't have figures for farmer suicides." There were no announcements, no relief packages, no loan waivers, no counselling camps, nothing. The very next day, five more farmers took their lives—two in Amravati, two in Washim and one in Bhandara.

This year, the Vidarbha region has received less than 25 per cent of normal rainfall, leading to second and third sowing. Ironically, less than 10 kilometres from Atmaram Shende's village is Telangtakli where farmers had to borrow to sow but their first sowing yielded results. "It rained here, we got water when we needed it," says Marotrao Madavi, a panchayat samiti member. He and other farmers in Telangtakli have heard of the suicides in next-door villages. Each time they hear a new story, they pray at the local Devi temple exhorting her to continue her largesse on them.

It's not only the monsoon that has failed the farmers. The state government has let them down too. The Maratha-dominated, sugar lobby-backed Congress-NCP government had declared western Maharashtra—the state's sugar bowl—drought-affected and moved relief measures there more than a month back.Unfortunately, little of the concern trickled down to Vidarbha.

Whether in Pada or Telangtakli, farmers are so deep in loans it'll take them at least a few years of normal monsoons to get out of the debt trap. Most of those who committed suicide had debts of nearly Rs 1 lakh each, some twice that amount. They had borrowed from rural credit societies and banks at 12.5 per cent interest per annum. But most of them began defaulting when their crops failed, making them ineligible for another loan. For thousands of farmers like Shende, Kinnake and others, there was only one recourse: the moneylenders.

There is perhaps no village in Vidarbha free of the latter's clutches. The normal rate of interest here is an astonishing 50 per cent. People like Nirmala Shende may not understand modern math but even she says, "For every Rs 1,000 we borrow, we have to pay back Rs 1,500. Each bag of soyabean seed costs Rs 800. Each bag of fertiliser costs Rs 350. So calculate, you'll know why we are indebted for life." According to Prakash Pohare, a journalist who turned activist two years ago over the issue of farmer suicides, the economics of farming has changed. "The prices of most inputs are now beyond the reach of most farmers. Each time they sow a crop, they go further into debt, irrespective of whether it's a good crop or not. It is the result of wrong government policies, bringing seed companies into a fairly self-contained production cycle," he says.

In spite of the suicides, the political response, though, has been stark indifference. The UPA government's rural emphasis did force Shinde to cast a glance at the Vidarbha farmers' plight. But little has come of that. The government or its representatives are rarely seen here, say villagers. As Kishore Tiwari of Vidarbha Jan Andolan put it, "Agriculture department officials are supposed to educate farmers on sustainable methods of cultivation, but they are nowhere. We see more agents and dealers of multinational seed, fertiliser and pesticide companies now." And the farmers have no option but to listen to these agents and dealers.

But in Yavatmal too, there are farmers like Anand Subedar and Subhash Sharma who farm the same cotton and soya on their 200-hectare and 36-hectare farms, and are showing the way. Subedar's model: back to basics with animal manure, no hybrid seed varieties and no synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.

Propagating this is nowhere on the government's agenda. Instead, the response has been to blueprint Rs 10,000 per hectare relief package, loan extensions, free education. All measures still on paper. It will be a few months and possibly some more suicides before any of this reaches Vidarbha. The Rs 1 lakh relief package to families of farmers who have committed suicide (announced last year) has so far reached only 22 families.

The discontent in rural Vidarbha showed up in the LS polls when the Congress-NCP lost all but one of the region's 11 seats. Now Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray has announced loan waivers and free power to farmers if the Sena-bjp combine is elected to power in the assembly polls this October. Tell that to women like Nirmala Shende. For them, elections are a ritual, they are more worried about the next rains, the next line of credit and the swelling number of suicide widows.

Tags